Theodore Roosevelt created Petrified Forest National Monument on December 8, 1906. Petrified Forest was designated as a national park on December 9, 1962. It is located in Navajo and Apache counties in northeastern Arizona. Named for its large deposits of petrified wood, the park covers about 346 square miles (900 square kilometers), encompassing semi-desert shrub steppe as well as highly eroded and colorful badlands.

The area of Arizona now contained within the Petrified Forest National Park was once part of a large forest that extended from Texas into Utah - the trees were similar to modern-day conifers and existed at the same time as the dinosaurs, fossils of which are often found in the park.

The petrified wood was formed 225 million years ago during the Triassic Period and is 4 times as hard as granite and very colorful, due to the effect of the mineral impurities that entered the wood during the fossilizing process. The Triassic was a time of a single world continent, when the first pterosaurs took flight and dinosaurs evolved along with many other animals.

During the Late Triassic Epoch of the Mesozoic era, the region that is now the park was near the equator on the southwestern edge of the supercontinent Pangaea, and its climate was humid and sub-tropical. What later became northeastern Arizona was a low plain flanked by mountains to the south and southeast and a sea to the west. Streams flowing across the plain from the highlands deposited inorganic sediment and organic matter, including trees as well as other plants and animals that had entered or fallen into the water. For example, The Crystal Forest Trail is named for the crystals that can be seen on the pieces of petrified wood shown here.

The colorful Chinle formation, mainly fluvial (river related) deposits, is up to 800 feet (240 m) thick in the park. It consists of a variety of sedimentary rocks including beds of soft, fine-grained mudstone, siltstone, and claystone—much of which is bentonite—as well as harder sandstone and conglomerate, and limestone. Exposed to wind and water, the Chinle usually erodes differentially into badlands made up of cliffs, gullies, mesas, buttes, and rounded hills. Its bentonite clay, which swells when wet and shrinks while drying, causes surface movement and cracking that discourages plant growth. Lack of plant cover makes the Chinle especially susceptible to weathering.

Much of the park’s petrified wood is from Araucarioxylon arizonicum, an extinct conifer tree, while some found in the northern part of the park is from Woodworthia arizonica and Schilderia adamanica trees. At least nine species of fossil trees from the park have been identified; all are extinct.

Petrification is the only process in the world in which a once living organism is transformed to mineral whilst remaining visibly very similar, conserving the original structure even down to microscopic details. The process of petrification is fundamentally different to that that creates other types of fossil, which in general have been formed by compression or impression of the original organism in mud or earth.

The park has many other kinds of fossils besides trees. The Chinle, considered to be one of the richest Late Triassic fossil-plant deposits in the world, contains more than 200 fossil plant taxa. Plant groups represented in the park include lycophytes, ferns, cycads, conifers, ginkgoes, as well as unclassified forms

The park has also produced many fossil vertebrates—including giant crocodile-like reptiles called phytosaurs, large salamander-like amphibians called Koskinonodon, and early dinosaurs. Fossil invertebrates include freshwater snails and clams. The dinosaur fossils are from the Late Triassic period, called the “dawn of the dinosaurs.”

Generally, Phytosaurs looks like modern crocodilian. It had a long snout, a mouth with conical teeth, short legs, long body with a long, heavy tail and thick armored skin. Some species had longer, thinner snouts with thin conical teeth for catching fish, while others had comparatively shorter, wider snouts with conical teeth in the front and ripping teeth in the back of the mouth. These were likely ambush hunters that snatched prey at the water’s edge, much like modern crocodiles. The longest known Phytosaur was 39 feet long and would have been about as tall as a human at the top of its back. Unlike modern Crocodilians, whose nostrils are at the end of their snouts, Phytosauria had their nostrils at the base of their snouts just above, or at the same level as their eyes. Phytosaurs are not related to modern Crocodilians. The similarities are an example of parallel evolution. This is when two different animals develop similar characteristics and attributes without a common ancestor.

This is a nicely preserved 1.4" long Phytosaur tooth still partially embedded in the sandstone in which it was found. It comes out of the Upper Triassic age Chinle Formation in Northeast Arizona. Much of the enamel has weathered away from this tooth, along with any visible serrations. The tooth is naturally associated with a small vertebra.

Fossils discovered recently at Petrified Forest National Park reveal a new species of a 220 million-year-old burrowing reptile known as a drepanosaur. This new species, named Skybalonyx skapter was announced on October 8th in a study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology in October, 2020.

The Skybalonyx is known to have lived during the Triassic period. It was only a little over a long foot long and looked like a cross between an anteater and a chameleon. It had claws that allowed it to burrow, which is what scientists say makes it unique. Jenkins and his colleagues were able to name the Skybalonyx, whose name translates to “dung-claw digger” in ancient Greek.

The paleontologists at the Petrified Forest National Park identified this new species of drepanosuars by analyzing the hand claws of modern animals and found that Skybalonyx skapter has claws most similar to burrowing animals such as moles, echidnas, and mole-rats, much different than other drepanosaurs that have claws suited for climbing and living in trees.

The Owl Rock Member consists of pinkish-orange mudstones mixed with hard, thin layers of limestone. While the red and green layers generally contain the same amount of iron and manganese, differences in color depend on the position of the groundwater table when the ancient soils were formed. The reddish soils were formed where the water table fluctuated, allowing the iron minerals to oxidize (rust). The Owl Rock Member is approximately 205 million years old.

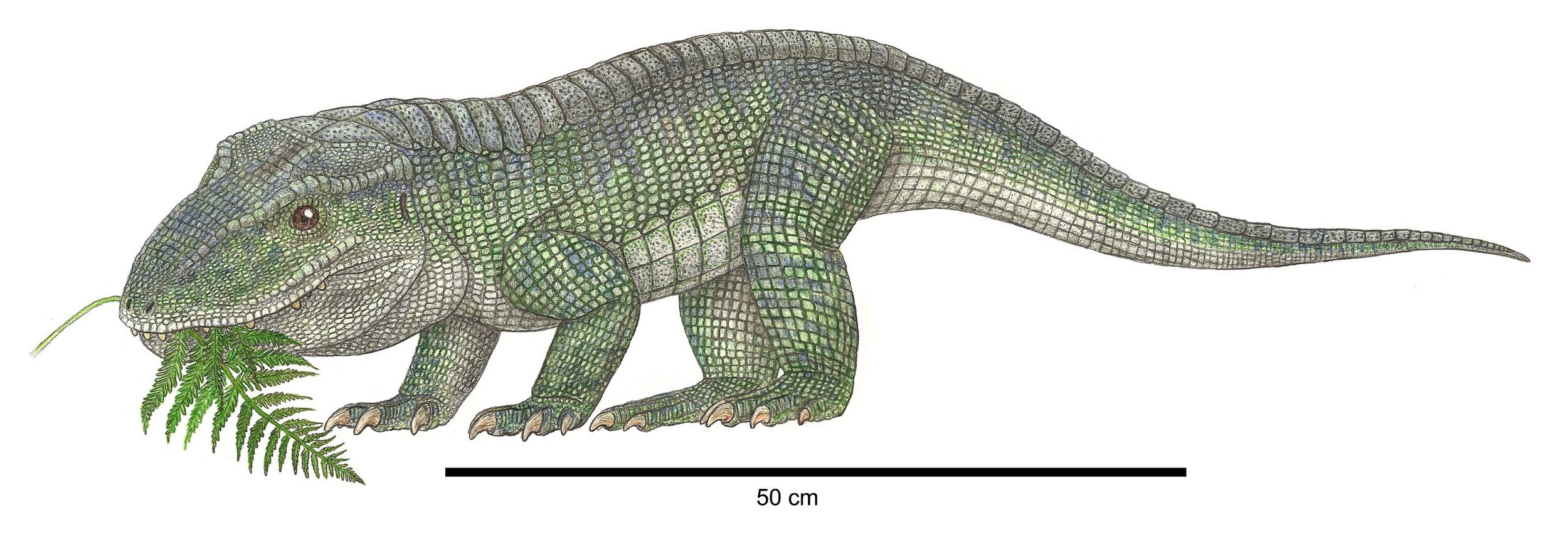

The fossilized skeleton of a small crocodile relative excavated in 2003 at Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona threw a wrench into theories of how and where the dinosaurs arose more than 210 million years ago at the end of the Triassic Period. The animal, one of many creatures from the Late Triassic known only from their teeth, previously was thought to be an ancestor of the plant-eating ornithischian dinosaurs like Stegosaurus and Triceratops, which roamed the world millions of years later in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Based on this new discovery the creature is most similar to a group of Triassic archosaurs - the group that includes crocodiles, dinosaurs and birds - called the aetosaurs.

Petrified Forest Park paleontologists, William Parker, stated, “This find is a great thing for the crocodilian record… The convergent evolution of the teeth is what makes them look like herbivorous dinosaurs. Thatʻs the only thing similar in the entire skeleton. There are no other dinosaur characters in the entire animal.”

The newly discovered full skeleton of a Revueltosaurus made it clear that the teeth are not of a plant-eating dinosaur, but of a herbivorous or perhaps omnivorous crocodilian ancestor living a mostly terrestrial life in the uplands of the Late Triassic. The new Revueltosaurus finds revealed crocodilian-like armor. This crocodilian ancestor was only three to four feet long, with a stubbier, less flattened skull and a less sprawling leg posture than todayʻs crocodiles have. Also, the armor did not cover the entire body, but was restricted to two lines down the back.

The preservation process of the trees found in the forest began during occasional flooding, when some of the trees were buried by a great depth of water and sediment quickly enough to prevent aerobic decay. Over a long period, water containing dissolved minerals seeped into the wood and replaced the organic cells with stone. Much later, the whole area was uplifted and eroded to give the landscape seen today.

Minerals such as manganese, iron, and copper were in the water/mud during the petrification process. These minerals give petrified wood a variety of color ranges.

The brightest colors are obtained when metals such as copper, chromium, cobalt, iron, and manganese enter the petrified wood’s structure. Copper, depending on the oxidation state, produces colors ranging from green to blue. Chromium and cobalt presence can also turn the material into blue or green, but slightly different hues. Iron, in the form of oxides (Fe2O3 or Fe2O4), produces all shades of brown from light yellow to almost black. Manganese makes petrified wood pink or even orange, while manganese oxides trigger dark shades up to uniform black. Residuals of organic compounds provide some carbon, which is responsible for all shades of gray and black.

The brilliant colors in this piece of petrified wood in the Petrified Forest National Park come mainly from three minerals. pure quartz is white, manganese oxides form blue, purple, black, and brown, and iron oxides provide hues from yellow through red to brown.

The minerals copper and manganese result in the blue-grey coloring in this piece of petrified wood.

The usual color of petrified wood is red, with yellow, black and white bands although other shades such as blue are often found. The bright red colors of the petrified forests of Arizona are due to high levels of iron, which can produce a range of hues depending on its oxidation state.

Deposits of silicon, ironoxide, magnesium and carbon.

Agate, a cryptocrystalline form of quartz, deposited in this tree resulted in this burst of translucent color ringed by red from iron oxide.

The Blue Mesa Member consists of thick deposits of grey, blue, purple, and green mudstones and minor sandstone beds, the most prominent of which is the Newspaper Rock Sandstone. This unit is best exposed in the Tepees area of the park. The Blue Mesa Member is approximately 220-225 million years old.

Pleistocene and Holocene Epoch (1.8 million years ago to present) deposits of windblown sand and alluvium (deposited by flowing water), now cover much of the older formations of the park. At higher elevations in the northern part of the park, 500,000-year-old dunes can be found. Younger dunes, around 10,000 years old, are found in drainage areas that contain sand such as Lithodendron Wash. The youngest dunes are found throughout the park, in all settings, deposited around a thousand years ago.

Similar to the American crow but larger, the common raven has a heavier bill and wedge-shaped tail. Highly intelligent and creative, ravens are primarily scavengers and opportunists. They can often be seen begging for food at overlooks and trailheads in the Park. This large raven came right up to our car, seemingly with the intent to obtain food.

We enjoyed watching this raven riding on rising air currents; but where you now see ravens soaring over a stark landscape, leathery-winged pterosaurs once glided over rivers teeming with armor-scaled fish and giant, spatula-headed amphibians. Nearby ran herds of some of the earliest dinosaurs.

On this day we were watched by members of a herd of pronghorns. Fauna in this National Park include larger animals such as pronghorns, coyotes, and bobcats, many smaller animals, such as deer mice, snakes, lizards, seven kinds of amphibians, and more than 200 species of birds, some of which are permanent residents and many of which are migratory.

One scary event occurred when while driving through the park a pronghorn running across the road almost crashed into the side of my car. When I caught the image in the corner of my left eye, I quickly swerved to the right while the pronghorn swerved to its left. We narrowly missed each other. I was thankful that I was not responsible in any way for hurting, or worse, one of these beautiful animals.

This pronghorn was motionless while watching me take this photograph. However, when needed, the pronghorn is the fastest land mammal in the Western Hemisphere, with running speeds of up to 55 miles per hour (89 km/h). It is the symbol of the American Society of Mammalogists.

Grasses are one of the most important plants within the grassland ecosystem found in the park. Large expanses of grasslands form where wind-blown sediment and erosion have created a layer of soil several feet thick. One of the most devastating causes of grassland destruction is grazing by livestock. Because grazing has not been allowed within the park for over fifty years, the area has returned to a more natural state and is one of the largest recovering grasslands in the Southwest.

The park has multiple species of cactus, including cholla, prickly pear, paperspine, and hedgehog. Cactuses are adapted to conserve water. The thickened, fleshy part stores water. The spines (highly modified leaves) protect against herbivores, deflect drying winds, and provide shade. The succulent stems carry out photosynthesis. Cactuses are native to the Americas from Patagonia to northern Canada.

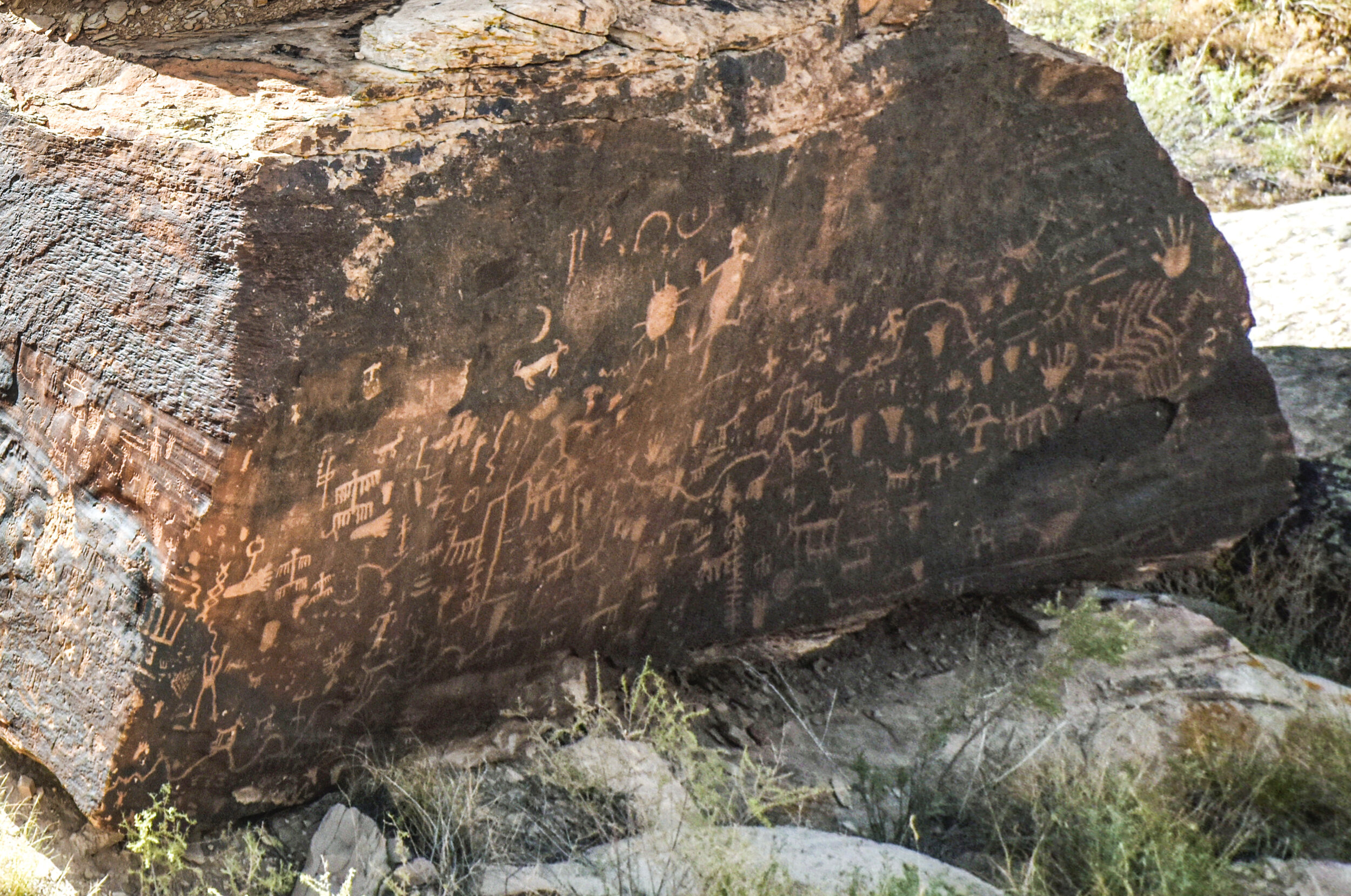

The park's earliest human inhabitants arrived at least 8,000 years ago. By about 2,000 years ago, they were growing corn in the area and shortly thereafter building pit houses in what would become the park. Later inhabitants built above-ground dwellings called pueblos. Although a changing climate caused the last of the park's pueblos to be abandoned by about 1400 CE, more than 600 archeological sites, including petroglyphs, have been discovered in the park.

In the 1800’s, train tracks traveled alongside the park. Between 1926 and 1985, Route 66 ran parallel to the tracks. These days, Interstate 40 has replaced Route 66, but a chunk of this historic road still remains. This 1931 Studebaker sedan commemorates U.S. Route 66, the decommissioned transcontinental highway, where it passed through Petrified Forest National Park in northeastern Arizona, United States.

For the discerning eye, each piece of petrified wood is a Natureʻs work of art. Each specimen contains unique hues of color and forms of creative design that have endured through changes in the earth over the last 225 million years. In addition, the Petrified Forest is well worth the visit for its expansive vistas, its stark moon-like landscapes, and for its colorful eroding badlands of the Painted Desert.