The ruins of the theater we see today were sited by ancient Greeks in the 3rd century BCE but re-envisioned during of Rome’s 600-year occupation. The Hellenistic theatre the Greeks built has all but disappeared beneath the layers of Roman brick and concrete. The Greek theatre became a Roman theatre in the 1st century CE and that theatre in turn was transformed into a gladiatorial arena 300 years later. The ruins at Taormina today are a 600-year compilation of Greek and Roman constructions, over two thousand years of wear and erosion, and countless patches and repairs performed by stewards of the theatre site.

In Greek theater, the scaenae frons was the building behind the stage used both as the back scene and the actors’ dressing room. During the Roman period, it was no longer painted in the Greek manner but tended to have architectural decorations combined with luxurious ornamentation.

According to 5th-4th century B.C. Greek pottery decoration the stage was built around 3.3 feet above the ground and had steps at the front. Actors performed on the stage which had an entrance on the left and right sides and from a single central doorway in the scenery behind, usually made to resemble a temple, palace, or cave. The use of painted scenery is also very likely. The stage scene could also have a top platform from which actors could play gods speaking down upon the audience and actors alike. Technical additions included a wheeled platform (ekkylema) pushed out of the doorway and used to dramatically reveal new scenery, and a crane (mechane) situated to the right of the stage and used to lift actors who were playing gods or heroes.

The theater’s cavea (semicircular tiered seating) has a diameter of 358 ft., seating 5,400 spectators. It is, except for that of Syracuse, the largest ancient theater not only in Sicily, but in the Italian peninsula and North Africa. The 3rd c B.C. Greek theater at Taormina was carved directly into the living rock of Mount Tauro . To carry out the gigantic work of the theatre, it was necessary to level the natural hill on which it stands and about 130,800 cubic yards of limestone rock was extracted. Large columns would have been hauled up the mountain by slaves to encircle the stage. Little of this earlier Greek theatre exists except for a few stone seats with 3rd century inscriptions and the remains of a Hellenistic sanctuary at the top of the cavea.

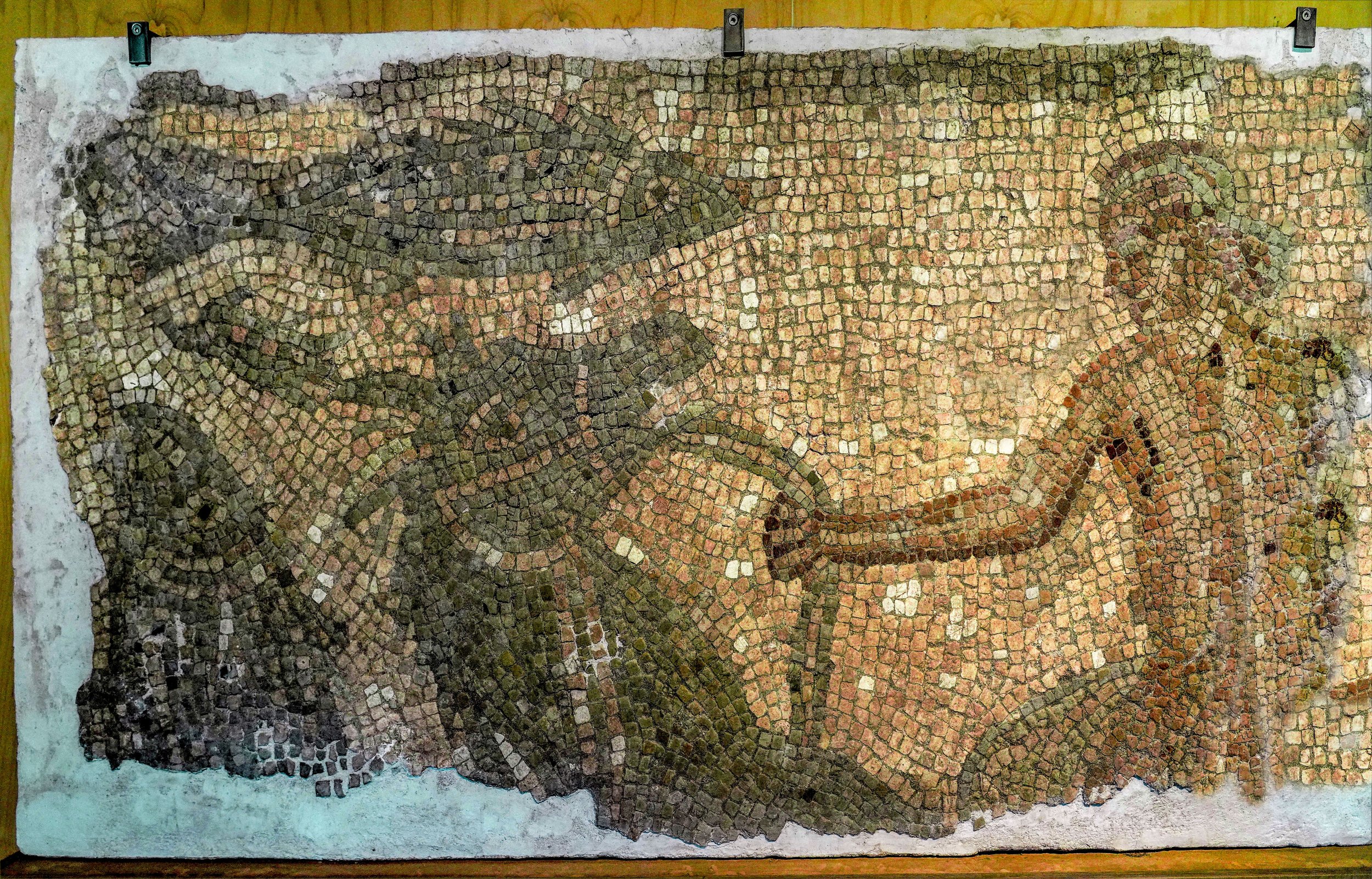

In the town of Taormina an extraordinary cultural heritage of mosaic floors has been discovered in private houses dating to the late Hellenistic period and Roman Imperial times (2nd century BC - 3rd century AD). This mosaic is an example of old restoration attempts of mosaics found in the 1950/60s inside private houses in Taormina that were mounted on rigid supports in reinforced concrete, fixed with iron braces and were then put on display on the corridor wall of the orchestra of the ancient theater.

As elements of the iconography of Dionysius (in Greek)/Bacchus (in Latin), maenads and satyrs are shown dancing and playing Bacchic musical instruments. Music and dance played an important role in bacchanalia, showing figures dancing.

In Greek mythology, the Niobids were the children of Amphion of Thebes and Niobe, slain by Apollo and Artemis because Niobe, born of the royal house of Phrygia, had boastfully compared the greater number of her own offspring with those of Leto, Apollo's and Artemis' mother: a classic example of hubris.

The Greek theatre was designed to accommodate dramatic or musical performances and so included an orchestra at the lowest levels of the theatre and a large scene where actors or dancers would perform. After the Punic Wars the Romans annexed Sicily, forcing out the Carthaginians. While Sicily remained largely Greek culturally, the Roman settlers expanded the theater and shifted its function to reflect Roman entertainment. The majority of the ruins we see today are the result of numerous Roman reconstructions and additions that began as early as the Trajanic/Hadrianic period, (98 to 138 A.D.).

The type of performances held in both Greek and Roman theaters were quite similar. Comedy and tragedy dominated, and theaters housed drama competitions and festivals to be carried out throughout the year. Masks, costumes, props, songs, and music all made up the show, with actors communicating with the audience directly or indirectly. Roman dramas, while originally taking themes from Greek topics and myths, eventually began to adopt their own themes with Etruscan and Latin origins. Choruses in Roman tragedies were incorporated into on-stage action, an aspect that differed from Roman comedy. Roman comedy were either Greek adaptations or entirely Roman in a Roman setting.

According to legend, Catherine was a princess who showed great intellectual prowess from childhood. As a young woman she had a vision of the Virgin and Child, and converted to Christianity. She was martyred for refusing to give up her Christianity. The accepted version of the saint’s life includes her asking Christ at the moment of her death to answer the prayers of those who remember her martyrdom and invoke her name. In the medieval Christian mind, this made her a powerful intercessor – i.e., she would intercede with God on behalf of the person praying.

As a princess, Catherine's attributes include a crown and royal robes, in addition to a palm frond, open prayer book and a sword. The palm frond pinned on her robe symbolizes that she was a martyr for her Christian faith even under torture. The sword she holds symbolizes her martyrdom and death by decapitation under the pagan emperor Maximinus, who ruled from AD 306 to 312. The emperor, over whom she triumphed, is shown crushed beneath her feet. The book in her left hand is symbolic of her intellectual achievements. Catherine’s legend may simply represent a of a series of persecutions of Christian women.

On the main altar you can see an imposing painting depicting Saint Catherine's martyrdom, attributed to the Sicilian painter Jacopo Vignerio (XVI century). Below the main portal there is a beautiful crypt fully excavated during the recent restoration, in 1977.

It seems to me that the Last Supper bas relief at the bottom of the altar of the Church of Saint Catherine owes much to Leonardo DaVinci’s version of the Last Supper. The St. Catherine version focuses on the same moment in the Last Supper, i.e., when Christ announced that one of the apostles would betray him. Christ’s arms and hands are in similarly posed as portrayed by DaVinci, having just established the sacrament known as the Holy Eucharist. At that point Christ announces the betrayal in both works. Finally, although the Saint Catherine Last Supper shows the apostles organized in different groups and their individual physical and psychological expressions are different from those of da Vinci’s apostles, both works of art provide the viewer with insight into the effect of Christ’s announcement oof betrayal on the apostles.

Mount Etna, view from the Ancient Greek/Roman Taormina Theater, Sicily