Welcome to the Stanza della Segnatura, one of the so-called Raphael Rooms in the Palace of the Pontiffs. I took the photographs while visiting the Vatican Museum in March, 2024. The best way to view the photos is to adjust your screen size so that you can scroll them up and down. This allows the explanations for each photo to be presented under the pictures instead of on top of them. (Four of the images, marked “internet,” are not my photos but were included in order to provide a somewhat more complete presentation.)

Pope Julius II commissioned Raphael to decorate the four rooms (stanze) of his Vatican apartments. Raphael worked from 1508 until his death in 1520. The four rooms are named - Room of Signatura (1508-1511), Room of Heliodorus (1512-1514), which were decorated practically entirely by Raphael himself; The Room of the Fire in the Borgo (1514-1517) and The Hall of Constantine (1517-1525) were designed by Raphael but largely executed by his pupils and by Giulio Romano.

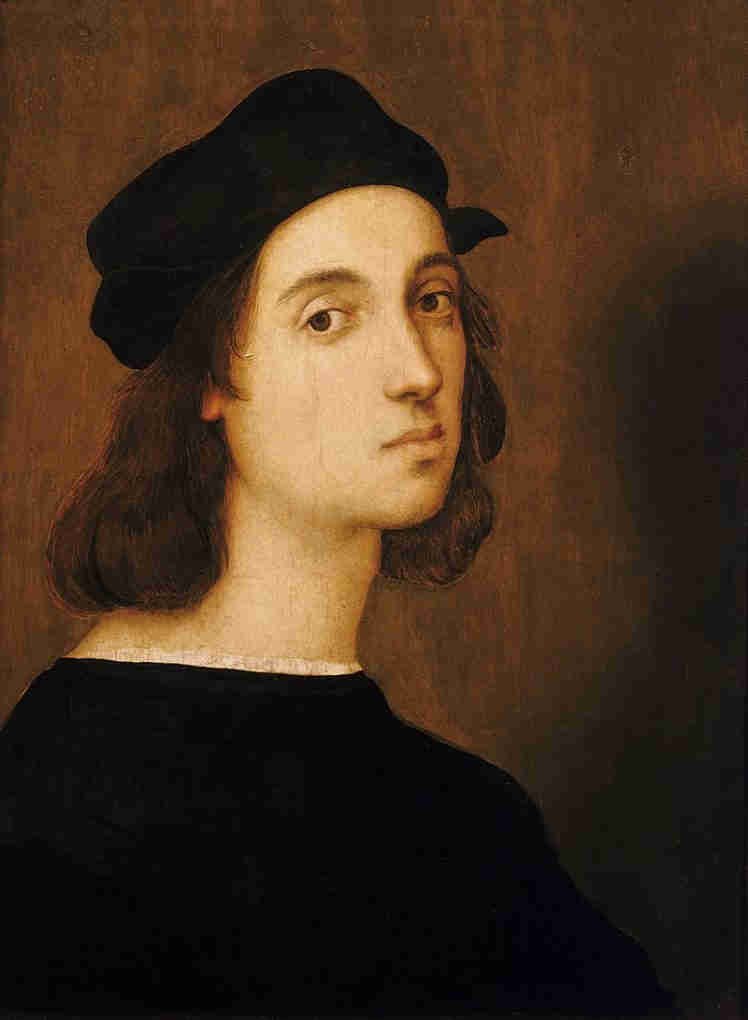

Raphael Sanzio was considered one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, as he mastered the signature techniques of the High Renaissance — sfumato, perspective, anatomical correctness, and authentic emotionality and expression. I photographed the frescoed Raphael Rooms, in the Palace of the Pontiff, the central and the largest work of Raphael's career.

The Stanza della Segnatura was named after the highest papal tribunal, whose judgments require the pope’s signature. With the theme of wisdom appropriately chosen for the room, Raphael presents the three greatest categories of the human spirit: Truth, Good, and Beauty. The Supernatural Truth is illustrated in the Disputation of the Most Holy Sacrament (Theology), the Rational truth is represented in the School of Athens (Philosophy). Good is seen in the Cardinal and Theological Virtues and the Law, while Beauty is represented in the Parnassus with Apollo and the Muses. The idea was to bring together natural philosophy and revealed theology, science and the arts, all under the supreme protection of the Church.

The figures on the ceiling of the Stanza della Segnatura complement the themes of the frescoes. The four women in the roundels point us to the central theme of each fresco. Above the School of Athens, we have Philosophy (top), above the Parnassus there’s Poetry (right), above the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament there’s Theology (bottom) and above the fresco of the Cardinal and Theological Virtues, we have Justice (left). In between these small frescoes, there are scenes that combine the categories.

Raphael’s Theology wears a white veil with green and red robes, which represent theological wisdom. Two putti hold signs stating "Divinar rerum notitia", i.e., "Knowledge of Divine things. In the panel to the left of Theology, Raphael portrays the story of Adam and Eve, who by rupturing the tacit covenant between them and God, thus established the need for religion and the Savior, Christ. In the right panel is the Greek myth of Apollo and Marsyas, the satyr, who was flayed to death, punished by Apollo, because of his hubris, i.e., he had dared to challenge a god.

La Disputa, the traditional name for what is really an adoration of the Most Holy Sacrament, portrays discussions concerning transubstantiation amongst the Church Militant (below) and the Church Triumphant (above). The painting is built around the focus of the disputation, in the center of the altar, the monstrance containing the consecrated Host, i.e., the body and blood of Christ; the Eucharist being the link between heaven and earth.

In Raphael's heaven we see, in the middle, the Holy Trinity surrounded by important Biblical figures, from left to right: Saint Peter, Adam, Saint John the Evangelist, David, Saint Lawrence, Judas Maccabeus, Saint Stephen, Moses, Saint James, Abraham, Saint Paul. They discuss the real presence of Christ as taught by St. Paul: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Corinthians 11:26-27).

The altar is flanked by men of the Church discussing the Eucharist, or Holy Communion, as the source and summit of Christian life. In 1551, the Catholic Church, via the Council of Trent, declared transubstantiation a dogma of faith stating that "by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.”

On the left of the altar, are seated Pope Gregory I and St Jerome (red robe). St Jerome's (b. 342-347; d. 420) translation of transubstantiation in the Latin Vulgate, the official Bible translation of the Catholic Church, reads: “Give us this day our supersubstantial bread.” This reference conveys the Church's teaching that the Eucharist becomes something above the ordinary matter or substance of bread. La Disputa represents Supernatural truth, i.e., that which cannot be known by the rational mind through science, but can be accepted through faith.

To the right of the monstrance are Augustine (with arm raised) and Ambrose, along with Pope Julius II (sitting). St. Augustine (circa 400 A.D.) upheld the concept of transubstantiation saying: “That Bread which you see on the altar, having been sanctified by the word of God, is the Body of Christ. …what is in that chalice, having been sanctified by the word of God, is the Blood of Christ.” Pope Sixtus IV (the uncle of Pope Julius II) is the gold-dressed pope, bottom of the painting), with Dante Alighieri (red robe and laurel wreath) standing behind him, and Aristotle (orange and blue robes) in front of Dante. In the back, fifth from right, stands St. Thomas Aquinas (with halo).

The Cosmati were a Roman family, seven members of which, for four generations, were skillful architects, sculptors, and workers in decorative geometric mosaic, mostly for church floors. Their name is commemorated in the genre of Cosmatesque work, often just called "Cosmati", a technique of opus sectile ("cut work") formed of elaborate inlays of small triangles and rectangles of colored stones and glass mosaics set into stone matrices or encrusted upon stone surfaces.

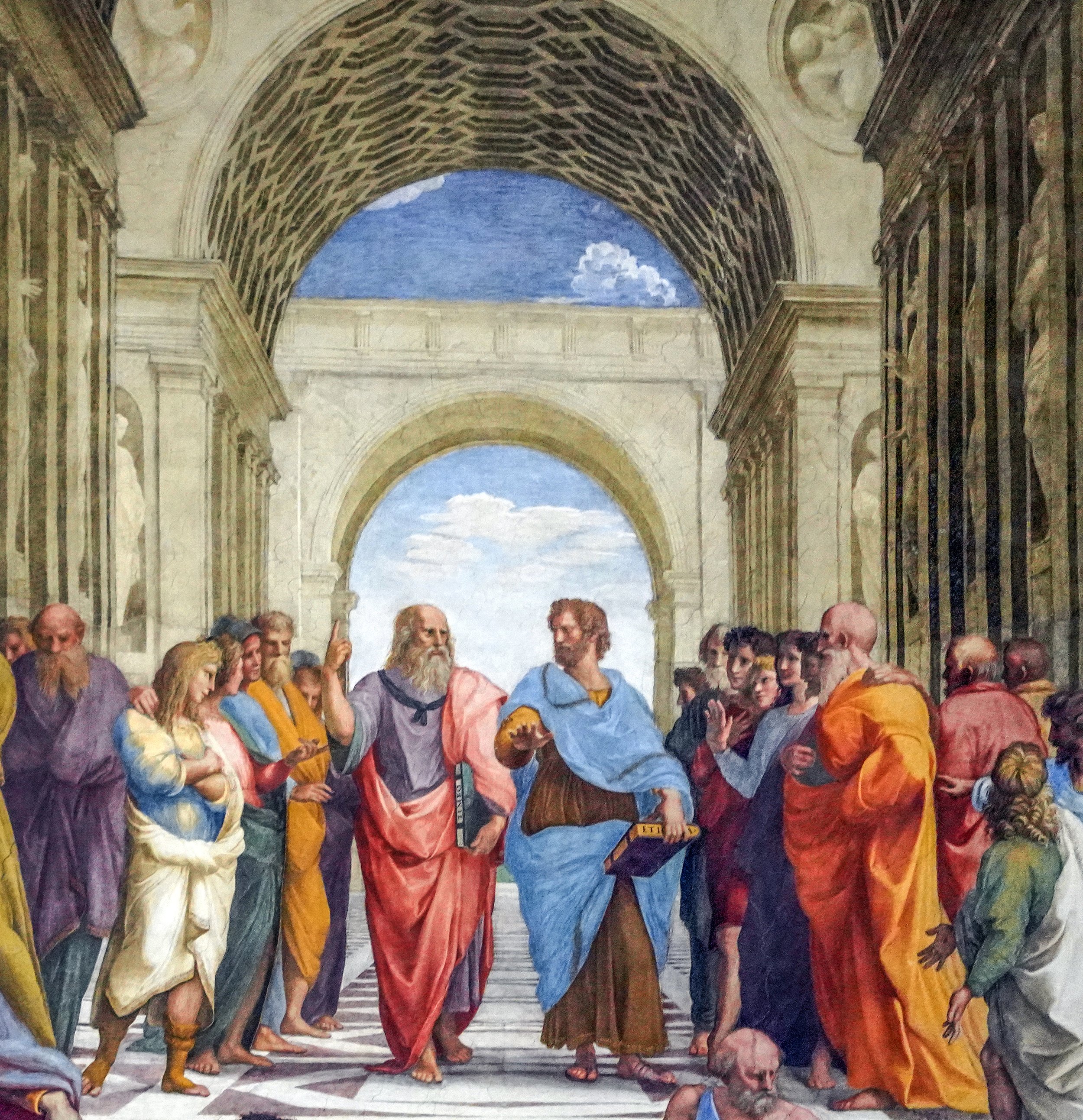

In the School of Athens, Raphael presents Plato and Aristotle’s notion of the Seven Liberal Arts, adapted in the medieval university as the foundational curriculum. There were two basic dimensions of study: one based on language, the trivium — made up of grammar, rhetoric and logic, and one based on numbers, the quadrivium — made up of arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. Together, study of these sciences would lead to a “unified idea of reality.” Raphael portrays the greatest scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers across time sharing their ideas and learning from each other.

The Prime Mover, philosophically, can be seen as an allegory of the beginning of the universe. The Prime Mover or Unmoved Mover is a philosophical concept described by Aristotle as a primary cause or “mover” of all the motion in the universe. As is implicit in the name, the “unmoved mover” moves other things, but is not itself moved by any prior action. In Book 12 of his Metaphysics, Aristotle describes the unmoved mover as being perfectly beautiful, indivisible, and contemplating only the perfect contemplation: itself. The figure looks down, and with her left arm and hand gestures to The School of Athens where Aristotle is a central figure.

Sitting above The School of Athens is “Philosophia,” representing the rational truth and holding two books: the red one "Moralis" (Morals), and the green one "Naturalis" (Nature). On the right of the Philosophy rondel Raphael depicts the Wisdom of Solomon, who decides to cut a baby in two in order to determine the true mother. Raphael painted The School of Athens, his allegory for science, on the wall opposite theology, i.e., La Disputa.

In the School of Athens, Raphael establishes an architectural framework, characterized by a high dome, a vault with lacunar ceiling and pilasters and fills it with figures in a variety of poses and gestures, which he controls in order to make one group of figures lead to the next in an interweaving and interlocking pattern, bringing the eye to the central figures of Plato and Aristotle, symbolically used for Philosophy at the converging point of the perspectival space.

Plato (c. 427 – 348 BC) and Aristotle (384–322 BC), his student, are the two central figures, standing under an archway at the center of the composition. The two men appear to be in an intense discussion, with Plato (left), holding his book Timeus, gesturing toward the sky, being engaged with such spiritual ideas as truth, beauty, and justice; and Aristotle (right), holding a copy of his Ethics, gesturing toward the ground, being concerned with worldly reality.

Raphael’s Staircase in The School of Athens has a dual meaning. In addition to its decorative dimension, it serves in fact as an allegory of knowledge. First, because it highlights the different degrees of philosophy and science. For Raphael, each character has a precise place on the ladder of knowledge, corresponding to his importance and prestige. Secondly, because the staircase illustrates the approach of philosophers and scientists: it is a path, an ascent to knowledge.

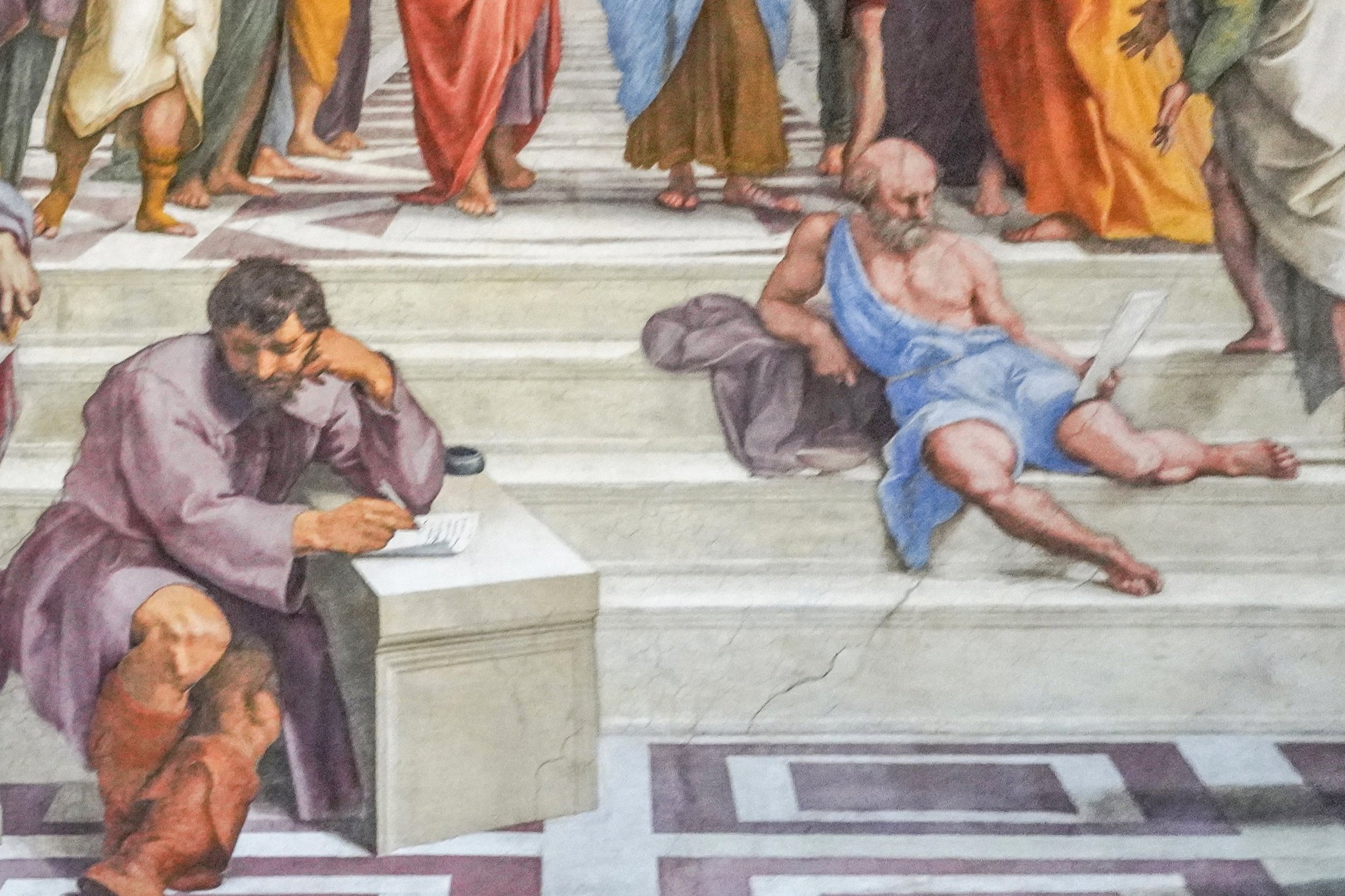

Sprawled out on the staircase steps below Plato and Aristotle, Diogenes (c.412 BCE-323 BCE), the unconventional Greek philosopher and founder of Cynicism, is seen reading in a relaxed pose. Diogenes made a virtue of poverty. He begged for a living and often slept in a large ceramic jar in the marketplace. He criticized the social values and institutions of what he saw as a corrupt, confused society. He also criticized Plato, disputing his interpretation of Socrates. The arch pessimist Heraclitus (b. circa 535 BCE) - thought to be a portrait of Michelangelo, who was then at work on the Sistine ceiling - is writing on a bench of marble. Heraclitus taught that there is nothing permanent except change, e.g., "No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man."

To the left of Plato and Aristotle, Raphael portrays Socrates (d. 399 BCE), wearing an olive green robe, and fingering syllogisms before a group, from left to right: Athenian statesman and general Alcibiades (450 BCE - assassinated 404 BCE), Greek philosopher Antisthenes (444 BCE-365 BCE) standing to his left wearing a black hat and a burgundy robe; Greek statesman Aeschines (389 BCE - 314 BCE), wearing a blue robe.

Standing facing forward is Hypatia (b. 350–370; d. 415 AD) a female philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician. She was a prominent thinker in Alexandria, Egypt, where she taught philosophy and astronomy and was renowned in her own lifetime as a great teacher and a wise counselor. To her right is possibly the mathematician and musician Nicomachus of Gerasa (c. 60- c. 120 AD) who authored Arithmetic Introduction. A Latin paraphrase of Nicomachus's works on arithmetic and music became standard textbooks in medieval education.

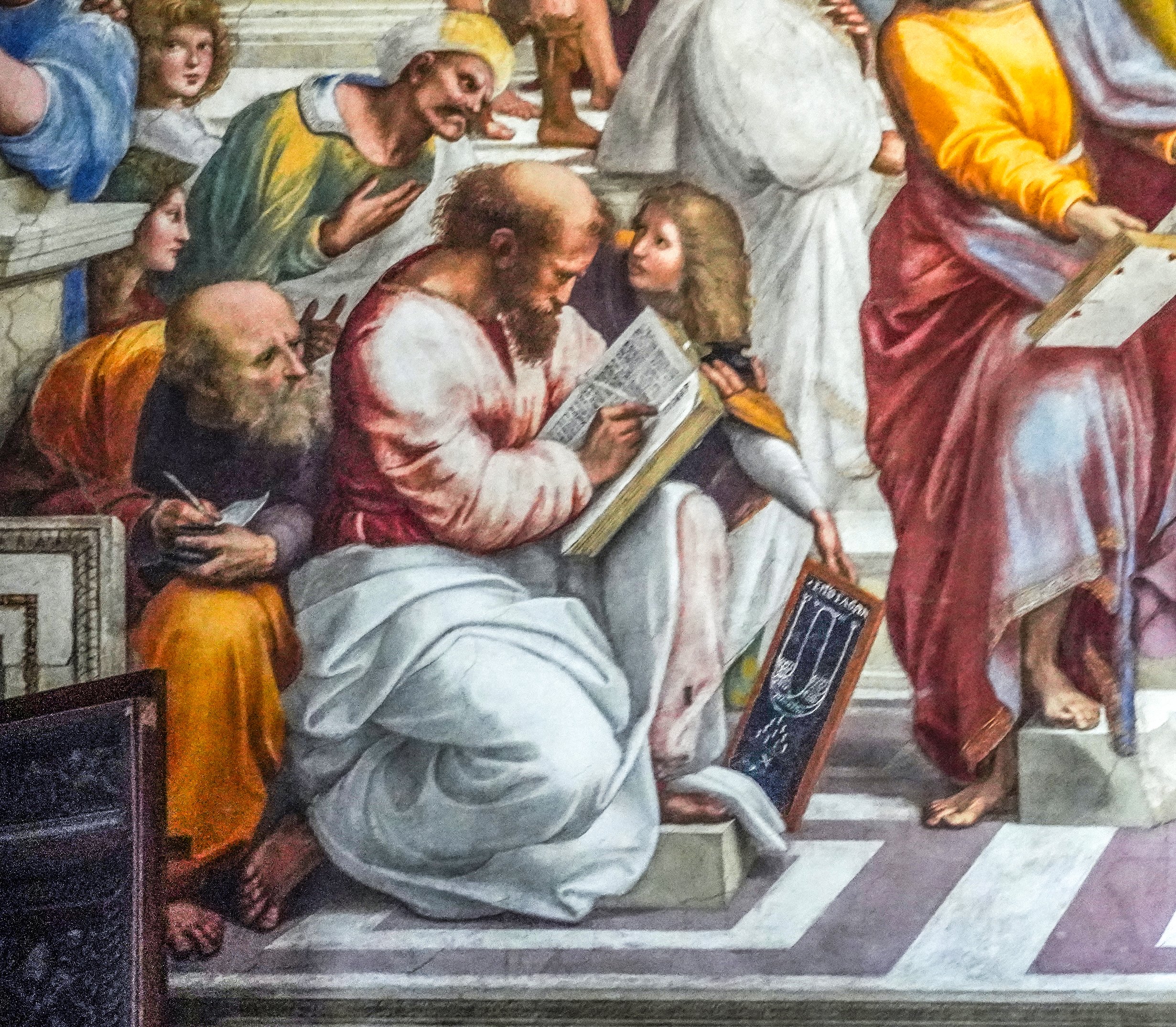

Pythagoras (kneeling, writing in book) believed that the world (including the movement of the planets and stars) operated according to mathematical laws. These mathematical laws were related to ideas of musical and cosmic harmony, and thus (for the Christians who interpreted him in the Renaissance) to God. A young man, Archimedes, helps him by holding before him a tablet with his Principles. Averroes is leaning behind Pythagoras and wearing a turban and a green robe; Anaximander (the first on the left in the foreground wearing a yellow robe) crouches, looking at Pythagoras’ work while writing on a sheet of paper.

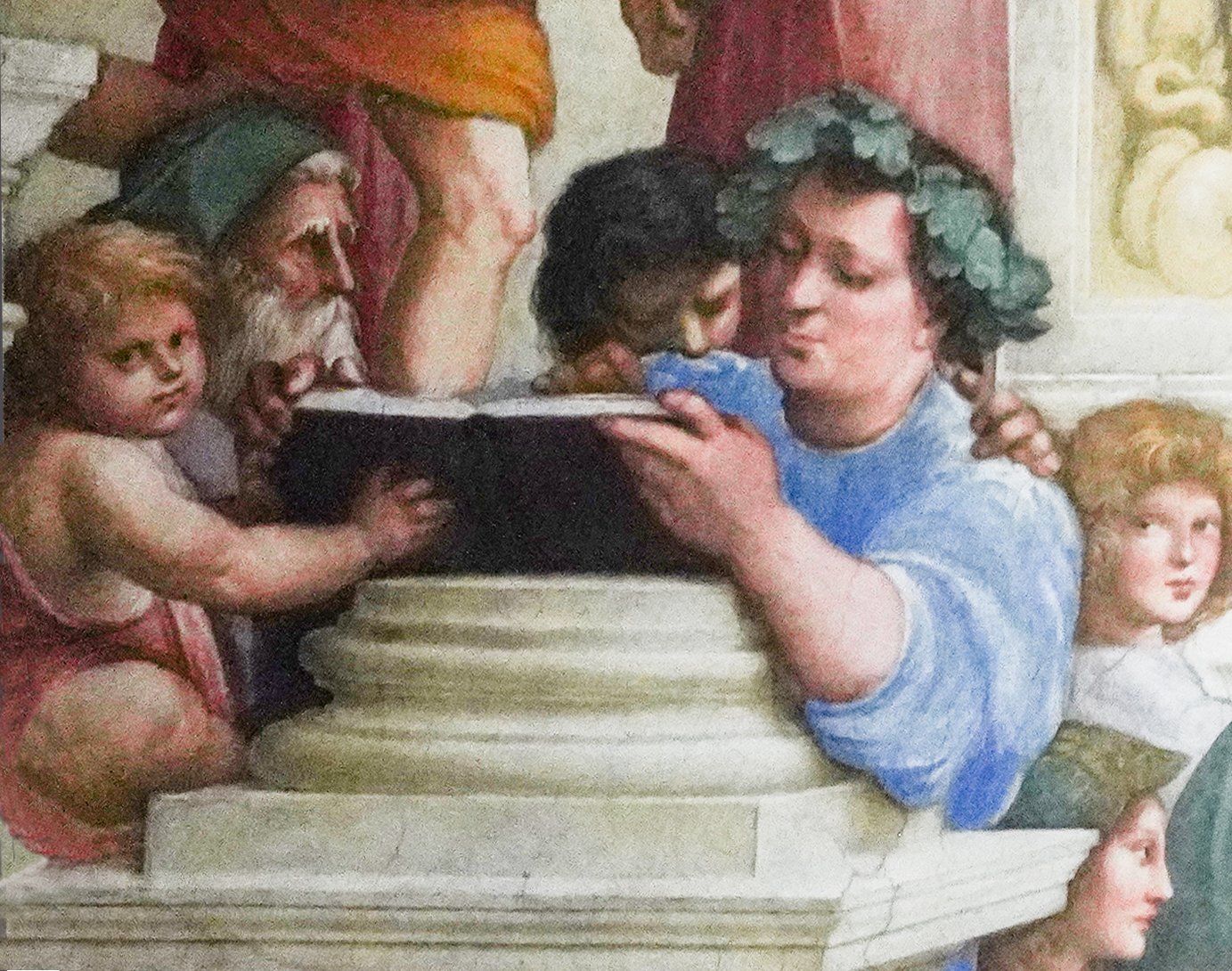

The head of Zeno of Citium is on the far left wearing a green hat and behind a small putto, and to his right is the Greek philosopher Epicurus leaning against a pedestal and wearing a crown of leaves on his head. Zeno was the founder of the Stoics School of philosophy, which he taught in Athens. Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature. Epicurus asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain happy (eudaimonic), tranquil lives characterized by ataraxia (peace and freedom from fear) and aponia (the absence of pain). He taught that people should act ethically because, due to the power of guilt, amoral behavior would inevitably lead to remorse weighing on their consciences and as a result, they would be prevented from attaining ataraxia.

Plotinus (204/5–270 C.E.), standing in a red robe, was a Greek philosopher and the founder of Neoplatonism, a school of philosophy that was influential in late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. Taking his lead from his reading of Plato, Plotinus developed a complex spiritual cosmology involving three foundational elements: the One, the Intelligence, and the Soul. It is from the productive unity of these three Beings that all existence emanates, according to Plotinus.

Euclid is shown teaching geometry to his students, and Zoroaster (facing forward) is represented holding the heavenly sphere, while Ptolemy (back to us) holds the earthly sphere. Euclid (fl. 300 BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician, and is considered the "father of geometry." Zoroaster was an Iranian religious reformer and the founder of Zoroastrianism, the first documented monotheistic religion in the world, founded in the second millennium BCE. He also had an impact on Heraclitus, Plato, Pythagoras, and the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Ptolemy tried to mathematically explain the movements of the planets. Raphael included a self-portrait, far right, looking forward, wearing a dark hat.

Raphael portrays himself as the Greek painter Apelles of Kos (facing forward, 2nd from right, wearing a black hat and standing behind his friend Sodoma, who is wearing a white hat). Raphael had been nicknamed by Vasari the "new Apelles.” Apelles was probably the most important Greek painter born about 370 BCE in Colophon. He worked for Alexander the Great and his father Philip. Apelles is famous for saying: “Not a day without a line”, i.e. do something every day!

In cosmati work you can find bands, panels and shaped reserves of intricate mosaic alternating with contrasting bands, guilloches and simple geometric shapes of plain white marble.

Poetry holds a Lyre, which is associated with Apollo, god of music, poetry and the arts. The putti hold signs stating "Numine and Afflatur" i.e., "Inspired by the Divine." In the panel to the right of Poetry, the concept of inspiration by the Divine is manifested by the image of the Prime Mover or Unmoved Mover, the primary cause of all motion in the universe. Also, the application of the science of astronomy in the panel might be Raphael’s homage to Pope Julius II, i.e., a constellation on the globe can be calculated exactly: the night of 31 October 1503, the date that Julius II was elected pope. Raphael was “inspired” by Julius’ decision that the room should be decorated to honor past officers and followers of the Church.

Mount Parnassus, according to Greek mythology, was sacred to Apollo and the home of the Muses. As the home of the Muses, Parnassus became known as the home of poetry, music, and learning. Raphael’s fresco, Parnassus, presents the god Apollo seated at the center, playing the lyre surrounded by the nine Muses, protectresses of the arts, and by ancient and modern poets, among whom Homer (blind), Virgil and Dante are easily recognizable behind him, as well as the poetess Sapphos seated at the bottom left, with her name written on the scroll she holds in her left hand.

The Cardinal and Theological Virtues and the Law is on the wall opposite the Parnassus. Raphael portrays Justice holding scales and a sword above the books on law. The more prominent position of Justice above the fresco is explained by the emphasis Plato placed on this fourth virtue. He introduced it to ensure the other three cardinal virtues existed in harmony. To the left of Justice is depicted Solomon’s wisdom via the story of two women who claim a baby as theirs and to the right is Adam and Eve whose justice was being expelled from paradise for breaking God’s law.

In the lunette below Justice, Fortitude, dressed in armor (left), sits in the shade of an oak tree (the oak tree symbolizes strength and alludes to the Della Rovere family to which Pope Julius II belonged). Prudence is placed on the highest step of the base. She has two faces: one of a young woman who looks at her reflection in a mirror handed to her by a winged putto; the other, of an old man, the symbol of old age, of which prudence is the chief quality. Finally, Temperance is represented holding a pair of reins. The three winged putti symbolize the theological virtues (Charity, gathering the fruits of the oak; Hope, in the center with a flaming torch; and Faith, at the extreme right, pointing toward the sky).

Below the frescoes presenting The Cardinal and Theological Virtues and the Law, there are two frescoes found lower on the wall also portraying scenes concerning the law.

To the left of the window below The Cardinal and Theological Virtues and the Law, is a fresco designed by Raphael but executed by his studio. It depicts the Emperor Justinian receiving the civil code known as the Pandects of the Corpus Juris Civilis from Tribonian (500 AD-542 AD), who was a Byzantine jurist and advisor. During the reign of the Emperor Justinian I, he supervised the revision of the legal code of the Byzantine Empire. These Pandects were important documents of Roman Civil Law that had been brought into accordance with Canon (Church) Law.

Below the to the right of the window, Pope Gregory IX (as portrayed by Julius II) receives the code of canon law known as the Decretals of Gregory IX from Raymond of Penyafort, a Catalan Dominican friar in the 13th century, who compiled the collection of canonical laws that remained a major part of Church law until 1917 when it was replaced. Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, later to be Leo X, is standing on the pope’s far left.