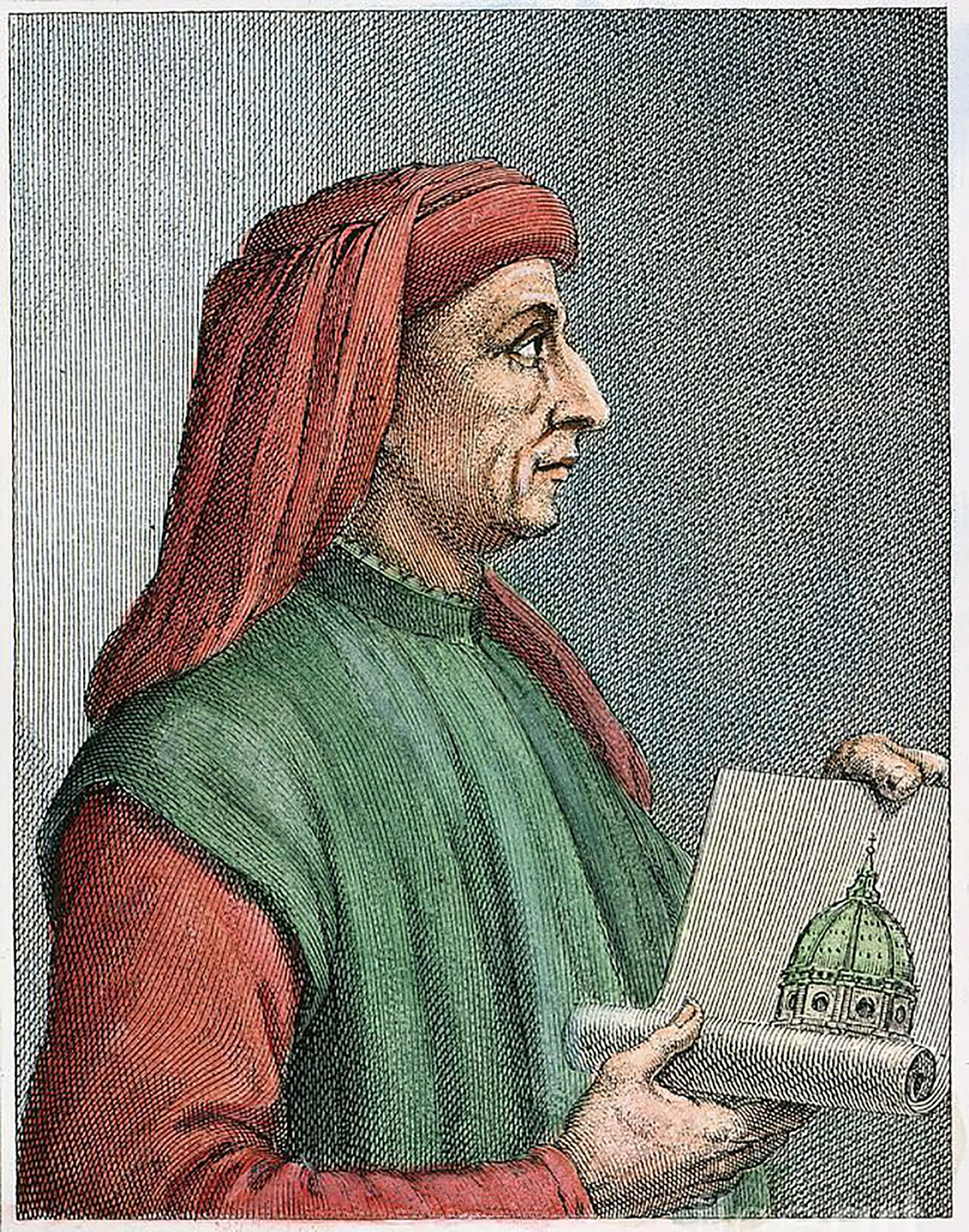

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) was the first architect to be acknowledged as a divine genius due in large part to his design and construction of the Dome on the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and for the machines he designed, built and used to construct that dome. Filippo was born in Florence (Firenze), Italy, a city with a long history marked by genius, and one in which there are reminders of that genius almost wherever one looks. I hope you enjoy this homage to Firenze, its history and to Brunelleschi’s world.

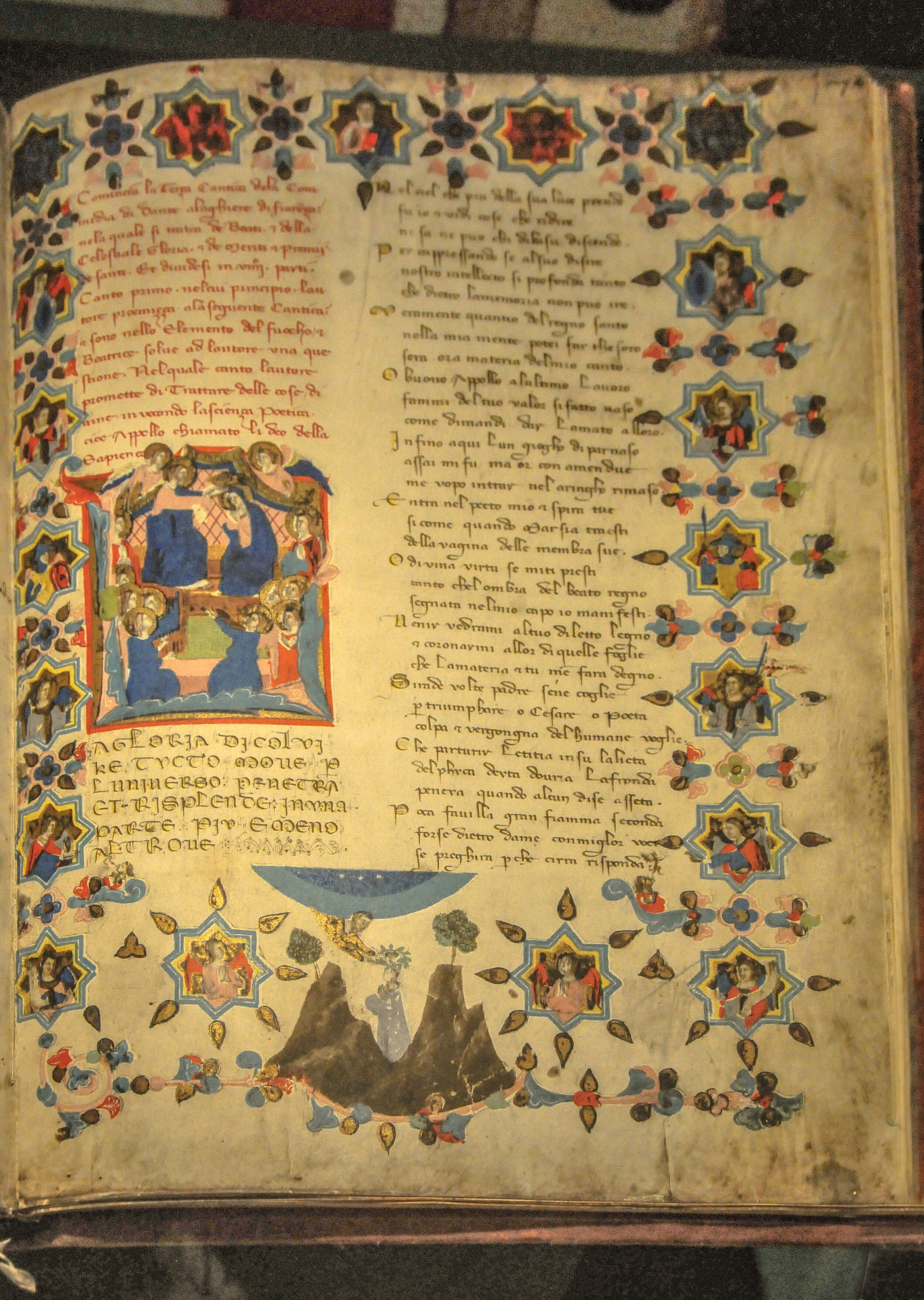

We can begin with the genius of Dante, an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa (modern Italian: Commedia) and later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio, is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language. The Divine Comedy was written in the vernacular Italian, instead of the more acceptable Latin or Greek. This allowed the work to be published to a much broader audience, contributing substantially to world literacy.

Dante’s The Divine Comedy (1308-1320) is a somewhat autobiographical work, set at the time in which he lived and peopled with contemporary figures. It follow's Dante's own allegorical journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso). Guided at first by the character of Virgil, and later by his beloved Beatrice, Dante wrote of his own path to salvation, offering philosophical and moral judgments along the way. The poet T. S. Eliot wrote, “Dante and Shespeare divide the world between them, there is no third.”

The Trivulziano Codex 1080, is a parchment volume written in 1337, by Francesco di ser Nardo da Barberino in Florence 16 years after the Dante’s death. It provides one of the most ancient and authoritative texts of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The calligraphy is an elegant chancery-cursive script, accompanied by fine miniatures that have been attributed to the anonymous Master of the Dominican Effigies.

Inferno (Italian for Hell) is the first part Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen".

Purgatory is depicted as a mountain in the Southern Hemisphere, consisting of a bottom section (Ante-Purgatory), seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (associated with the seven deadly sins), and finally the Earthly Paradise at the top. In describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem outlines a theory that all sins arise from love – either perverted love directed towards others' harm, or deficient love, or the disordered or excessive love of good things.

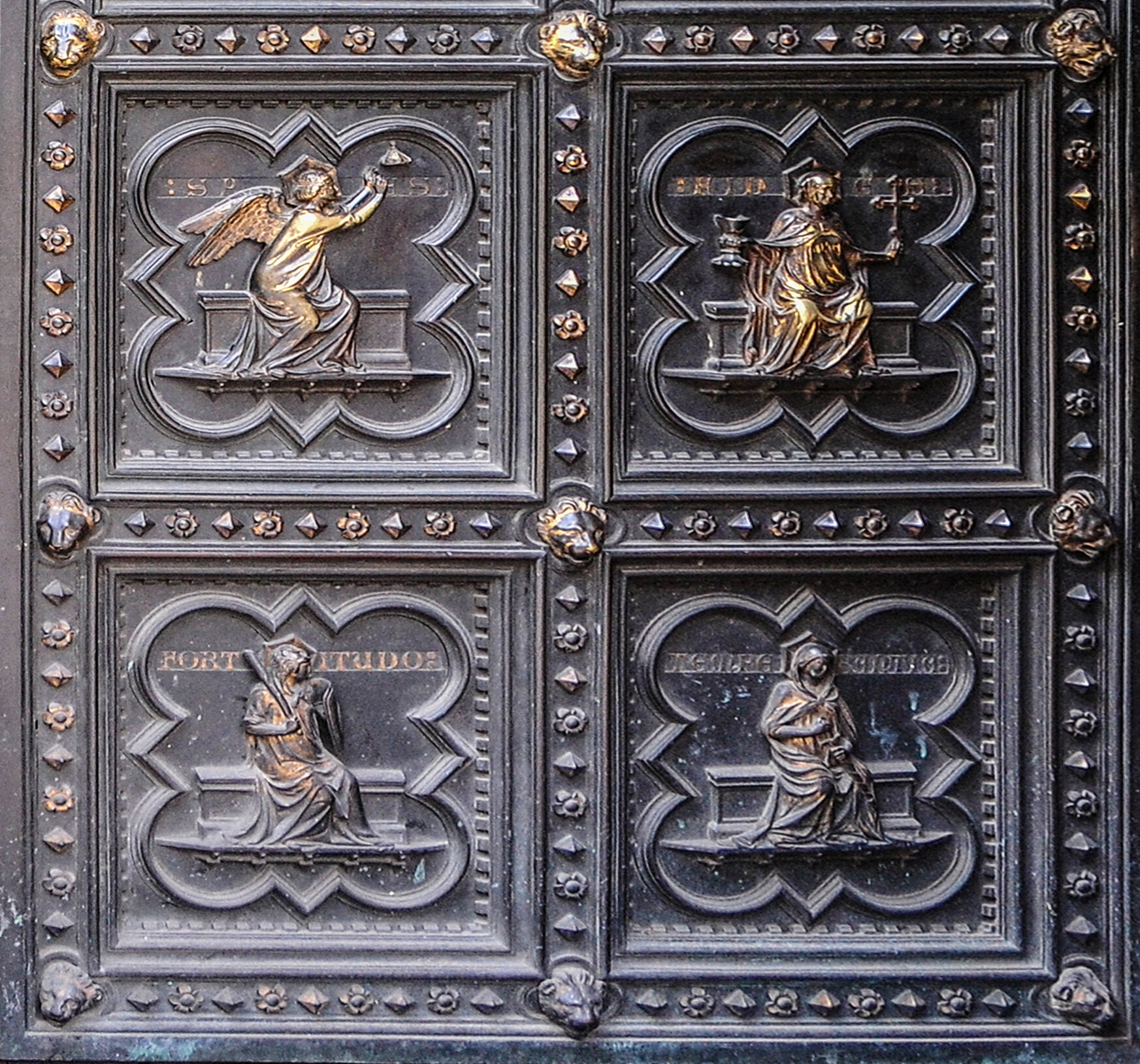

While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatorio were based around different classifications of sin, the structure of the Paradiso is based on the four cardinal virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity). Dante's journey through Heaven is guided by Beatrice, who symbolizes theology. In the poem, Paradise is depicted as a series of concentric spheres surrounding the Earth, consisting of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, the Primum Mobile and finally, the Empyrean. It was written in the early 14th century. Allegorically, the poem represents the soul's ascent to God.

The design of the original Florentine florins was the distinctive fleur-de-lis badge of the city on one side and on the other a standing and facing figure of St. John the Baptist wearing a hair shirt. The Florentine florin was a coin struck from 1252 to 1533. It had 54 grains of nominally pure or 'fine' gold (3.5368 grams, 0.1125 troy ounce) with a purchasing power ranging from approximately 140 to 1000 modern US dollars. As many Florentine banks were international supercompanies with branches across Europe, the florin quickly became the dominant trade coin of Western Europe for large-scale transactions. This wealth allowed for the building of the Cathedral and the many commissions given to the artists, architects, and artisans of Firenze.

The three-story palace was designed by architect Lapo Tedesco, as police headquarters, tribunal, and prison. Converted in 1865 into a museum, the Bargello was the first Italian museum exclusively dedicated to medieval and Renaissance art.

Giambologna’s (Jean de Boulogne) work emphasized refined surfaces, cool elegance, and beauty. This sculpture was commissioned for the Sala del Cinquecento (the Great Council Hall) of the Palazzo Vecchio. Created in time for the wedding of Francesco I de' Medici and Joanna of Austria, Cosimo I de' Medici intended for the Great Council Hall in the Palazzo Vecchio to be decorated with depictions of Florentine military triumphs.

At the age of 23, Donatello carved this conventional 6-foot tall marble sculpture of David to top one of the buttresses of Santa Maria del Fiore, though it was never placed there. He portrays David victorious, after having defeated the giant Goliath, whose head figures at his feet with the stone that killed him still stuck in the middle of the forehead. The pose and the attitude express a conscious pride. At his feet the inscription "Pro patria fortiter dimicantibus Etia adversus hostes terribilissimos Dii prestant auxilium" ( "The gods give support to the brave fighters for their country even against the most fearsome enemies".) which underlines its political significance as a symbol of untamed and libertarian nature of the Florentine Republic, a small republic that fought against great powers.

Donatello created his bronze statue of David 32 years after the marble David (above) he had sculpted in his early twenties. Commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici, Donatello’s bronze David is considered one of the greatest sculptures of the 14th century. Donatello's two statues of David illustrate the development of his style and vision from the heavy Gothic influence of his youth, characterized by ornament and grace, to a more naturalistic style of his later years that was less idealized and more realistic. His body appears lithe as he stands with one foot atop Goliath's decapitated head. His small frame and almost effeminate disposition imply that his victory is due to God's assistance. He holds a sword which looks huge in proportion to his body and smiles proudly. This David is credited with being the first free-standing male nude statue since the era of Greek sculpture.

This bronze statue of David was commissioned by the Medici family. It is sometimes claimed that Verrocchio modeled the statue after his pupil Leonardo da Vinci. The statue represents the youthful David triumphantly posed over the head of the slain Goliath. David holds Goliath’s sword in one hand and rests the other on his hip in a gesture of confident triumph. David, the biblical hero and future king of Israel who achieved victory over a tyrannical adversary, was embraced by Florentines as a symbol of liberty and good government.

A statue of David was originally commissioned in 1464 as one of a series of statues of prophets to be positioned along the roofline of the east end of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. The commission was given to Agostino, who stopped working on it in 1466, and then, 10 years later, to Antonio Rossellini, who also did not finish the project. In 1501 the original block of Carrara marble used by the earlier sculptors was given to Michelangelo to create a David. On September 8, 1504 it was placed in a public square outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of civic government in Florence, in the Piazza della Signoria.

St Matthew is an unfinished marble sculpture created in 1505-6. The 8.9 feet (271 cm) tall sculpture was originally planned to be one of a group made up of all the Apostles and destined for niches of the choir of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. St Matthew. After some months working on the sculpture of St. Matthew, the figure took shape as if struggling to emerge from the marble. The effect of movement inherent in the sculpture makes it very different in pose to David. St. Matthew was the only Apostle statue started and the project was abandoned early in 1506 when Michelangelo was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II to sculpt 40 statues for his tomb.

Dancing, with his arms in the air, the 4.5 feet boy has a pagan and carefree demeanour. He has winged feet, which initially led scholars to believe he may be Eros or Cupid. However, as he has his buttocks and genitals displayed through open and loose trousers, he could also be Attis, the beautiful young shepherd who castrated himself in an act of induced madness. After all the deliberations, researchers settled on the name we know the boy by today, Amor Attis. This seems to be a compromise between the sensual and forbidden nature of Attis and all his joyful abandon, and the obvious and symbolic references to Ero, God of love.

This sculpture, with its striking theatrical pose and accurate anatomical representation, portrays a youth of rare beauty, whom Venus, unrequited, fell in love with. One day while out hunting, Adonis was mortally wounded by a wild boar and not even the goddess was able to reach him in time and save him. The marble statue was purchased by Isabella, daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici, a major supporter of Brunelleschi, for the villa of Poggio Baroncelli where it remained until 1873.

This statue was originally commissioned by Cardinal Raffaele Riario. However, it was rejected by him and eventually found its way to Jacopo Galli, Cardinal Riario’s banker and a friend of the sculptor, who purchased it in 1506. Some 66 years later it was bought for the Medici and transferred to the royal house in Florence, Italy. It is one of just two sculptures surviving Michelangelo’s initial period in Rome, with the other being Pieta.

This Bacchus is one of the first monumental bronzes (7’ 8.5”) made by the Flemish sculptor, Giambologna (Jean de Boulogne), affected, in style, by the influence of Benvenuto Cellini. The original bronze was saved by a bombardment of the German occupation forces during World War II and was relocated in Borgo S. Jacopo in this niche. The City commissioned a replica to the Fonderia Marinelli, which in 2006 took the place of the original Bacchus, now exhibited at the Museum of the Bargello. The mold used to execute the bronze work, using the lost-wax casting process, was produced directly on the original.

“Mercury” is Giambologna’s most famous work. The statue represents the messenger of the gods as a harmonious and able nude figure, in artificial balance on the breathe of Zephyr. It was originally sent to decorate the fountain at the entrance to the garden of Villa Medici in Rome, residence of Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici.

It is believed that the Baptistry was built over the ruins of a Roman temple dedicated to Mars dating in the 4th-5th century A.D. It was first described in 897 as a minor basilica. In 1128, it was consecrated as the Baptistery of Florence and as such is the oldest religious monument in Florence. The octagonal baptistery stands across from Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore. The Baptistery is renowned for its three sets of artistically important bronze doors with relief sculptures. The Italian poet Dante Alighieri and many other notable Renaissance figures were baptized in this baptistery.

These 8 ft. tall bronze statues were placed over the southern doors of the Baptistery in 1571. In the Beheading of St John the Baptist the central St John kneels awaiting his martyrdom, while on the right the elegantly poised executioner holds his sword aloft and on the left is Salome, Herod's daughter. The group stood over the southern doors until the restoration in 2008; then the statues were replaced by copies and this original group is now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo.

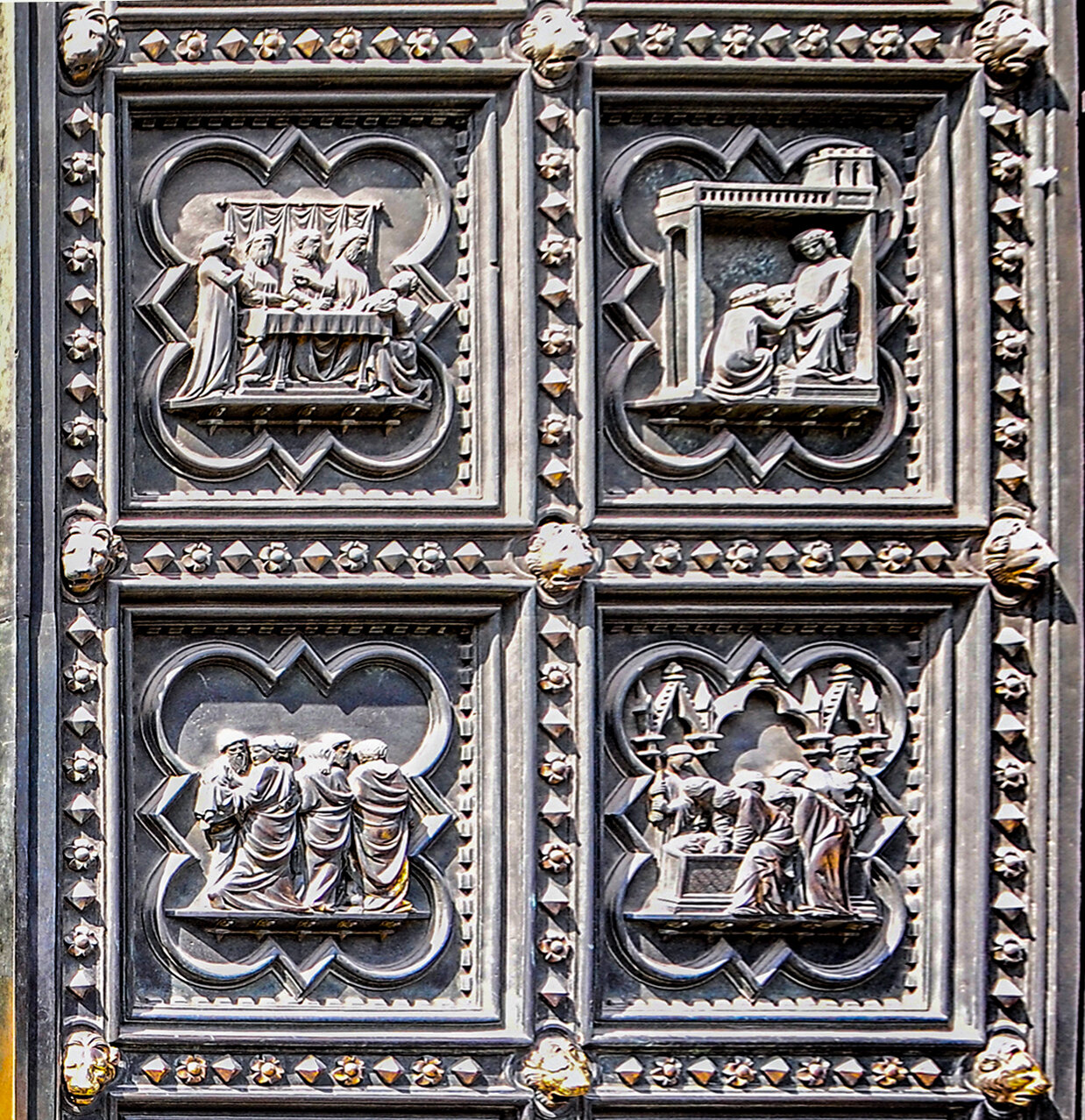

Andrea Pisano designed the earliest of the three doors for the Baptistry with 20 quatrerfoil panels containing scenes from the Life of St. John the Baptist and 8 with figures of virtues. The figures are gilded and set against a smooth bronze surface.

ToTop Left: The Visitation (Mary, pregnant with the infant Jesus visits her cousin Elizabeth. At the sound of Mary’s greeting, Elizabeth, who was 6 months pregnant, felt the infant St. John the Baptist leap in her womb, which, according to later doctrine, signified that he had become sanctified and cleansed of original sin.). Top Right: The Birth of the Baptist; Bottom Left: Zachariah (the father of John the Baptist) writes the boy’s name: Bottom Right: St. John as boy in the desert.

Top Left: John the Baptist Preaches to the Pharisees; Top Right: John announces Christ; Bottom Left: John baptizes the disciples; Bottom Right: John baptizes Jesus.

Top Left: Hope; Top Right: Faith; Bottom Left: Fortitude; and Bottom Right: Temperance

The right side of the South Doors also contains 10 panels of scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist and 4 panels depicting virtues.

Top Left: Presentaion of St. John’s head to Herod Antipas; Top Right: Salome takes the head to Herodias; Bottom Left: Transport of the body of St. John; and Bottom Right: Burial of St. John the Baptist.

Top Left: Charity; Top Right: Humility; Bottom Left: Justice; Bottom Right: Prudence. Note: The virtues used on Andrea Pisano’s south door are those Dante had used earlier in his Paradiso, which he based on the four cardinal virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the three theological virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity).

Ghiberti’s northern doors depicts stories of the Life and Passion of Christ taken from the New Testament. Above the northern door were located three bronze statues, modeled between 1506 and 15011 by Giovanni Francesco Rustici, depicting St. John the Baptist Teaching between the Pharisee and the Levite. Ristici’s originals are now in the Opera del Museo and have been replaced with copies.

Rustici’s three bronze statues, each with its own pedestal (standing 8.5’ in height), were placed above Ghiberti’s northern doors. St John, the patron saint of the city and building, is emphasized by his central placement and the poses and gazes of the flanking figures. The above original statues were replaced on the Baptistry with copies. Rustici was considered by his contemporaries as one of the major sculptors in Tuscany. He shared a house during the commission with Leonardo da Vinci and may have received technical advice from da Vinci.

In 1401, a competition was announced by the Arte di Calimala (Cloth Importers Guild) to design doors which would eventually be placed on the north side of the baptistery. At the time of judging, Ghiberti and Brunelleschi were the finalists, and when the judges could not decide, they were assigned to work together on them. Brunelleschi's pride got in the way, and he went to Rome with Donatello to study architecture leaving Ghiberti to work on the doors himself. Ghiberti’s gilded bronze doors consist of twenty-eight panels, with twenty panels depicting the life of Christ from the New Testament. The eight lower panels show the four evangelists and the Church Fathers Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory and Saint Augustine.

Top Left: Chasing the merchants from the Temple; Top Right: Jesus walking on water and saving Peter; Bottom Left: Adoration of the Magi; Bottom Right: Christ among the doctors.

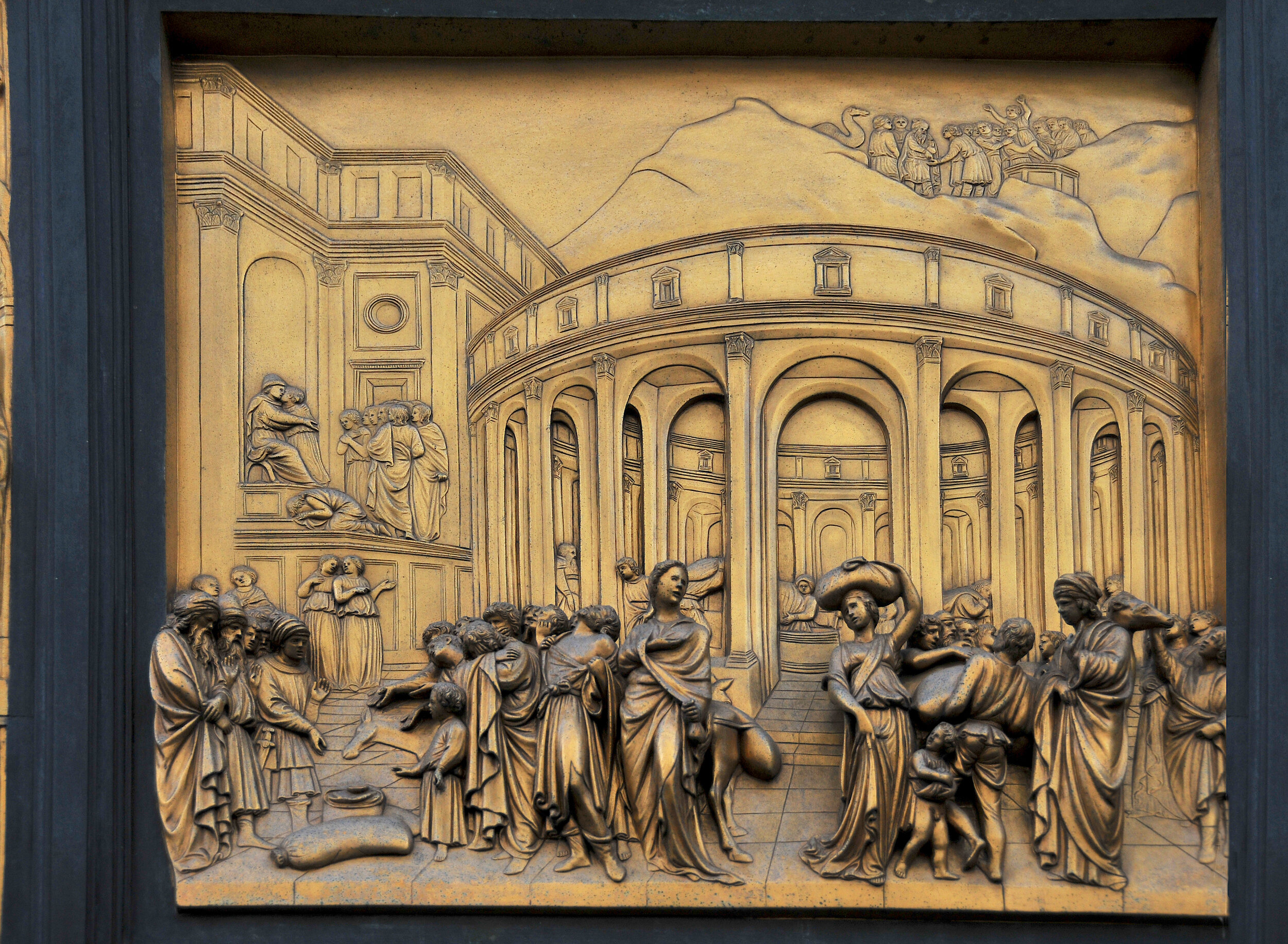

The East doors, referred to as “The Gates of Paradise,” received that name from Michelangelo who is believed to have exclaimed: “they are so beautiful that they would be perfect for the gates of paradise.” Just as early Renaissance painters sought to create an illusion of depth, Ghiberti studied perspective and applied it to his relief sculpture. Rather than his reliefs being figures attached to a flat background, he sculpted the entire surface to create an illusion of pictorial depth. With regard to the “Gates of Paradise” he said “I sought to imitate nature as closely as possible.”

In the period following his return from Portugal to Italy, Sansovino became established as a sculptor of large-scale figures. The monumental marble figures above, standing at heights of 8.5’ to 9’, were placed over the east doors of the Baptistery. These original statues are in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. They were replaced over the east door by copies.

The panels are large rectangles and are no longer embedded in the traditional Gothic quatrefoil, as in the previous doors. Ghiberti employed the recently discovered principles of perspective to give depth to his compositions. The east doors consist of 10 rectangular panels, displayed in two lines. They depict scenes of the Old Testament. In each panel Ghiberti described more than one scene so that there are over fifty scenes depicted. All around the frame of the doors Ghiberti added 24 small bronze busts of famous Florentines, including his own self-portratit.

The biblical Book of Genesis speaks of the relationship between fraternal twins Jacob and Esau, sons of Isaac and Rebekah. The story focuses on Esau's loss of his birthright to Jacob and the conflict that ensued between their descendant nations because of Jacob's deception of their aged and blind father, Isaac, in order to receive Esau's birthright/blessing from Isaac. The bronze panel follows several episodes from the Bible story: 1) Rebecca's conversation with God before the twins are born, 2) Rebecca on the birthing bed, 3) Esau's selling of his birthright to Jacob for a pot of porridge, 4) Isaac telling Esau he will be blessed if he goes and hunts, 5) Esau's leaving for the hunt, 6) Rebecca's instructing of Jacob in the deceit, and 7) Jacob's receipt of the blessing. On the bottom right corner of the frame is a self-portrait of Ghiberti.

In the foreground depicts all the tribes of Israel gathered at the bottom of the mountain in order to witness this historic moment. It is the rocky mountain that perhaps grabs the eye first, with the sculptured surface protruding out from the surface of the artwork to give a three dimensional finish. Moses and his interaction with the heavens, the focal point of this narrative, is located in the upper right of the panel. The multitude of figures at the bottom adds further interest and also allows Ghiberti to further confirm his exceptional skills of portraiture.

Ghiberti’s “David and Goliath” provides a very literal description of the difference in size between the two warriors, placing them at the bottom of this panel. Multiple soldiers from both sides look on in awe as David protects his town by slaying Goliath. Their town sits in the background at the top of the panel, seemingly unaware of the sacrifices being made in its honour. Lorenzo Ghiberti again uses a rocky landscape in between in order to separate the two parts of the composition, with some additional trees that aim to soften the area beneath the rocks.

The Queen and King stand in front of Solomon’s great Temple of Jerusalem, the dwelling-place of God on earth. Ghiberti’s classical pillars and gothic arches seem to owe rather more to the cathedral of Florence than to the ancient structure in Jerusalem. In the centre of the composition, below the great porch, stand Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. They turn towards each other holding hands, in a pose which looks very like that of a marriage. It has long been suggested that this panel was intended as a commemoration of the impending Council of the Eastern and Western Churches, which opened in Florence in 1439. The Queen, as representative of the Eastern Church, and King Solomon as the Western Church, stand together in a glorious union, blessed by God. Ultimately the attempt to heal the Great Schism was a failure.

Ghiberti tells the story of the Fall of Jericho according to Joshua 6:1-27, that the walls of the city of Jericho would fall after Joshua's Israelite army had invaded and sounded their trumpets around the city. The outline of this story is clear to see within this artwork, with the architectural scenery found in the background and a multitude of figures in the foreground, seemingly in discussion rather than battle at that point. This is perhaps one of the most detailed panels for the Gates of Paradise series, with visual interest spread right across the bronze panel. The tents are perhaps the most impressive part of this panel, with then the fortified city in the background also displaying the artist's growing knowledge of depicting architectural scenes and also putting perspective accurately into artwork.

In "The Story of Joseph" is portrayed the narrative scheme of Joseph Cast by His Brethren into the Well, Joseph Sold to the Merchants, The merchants delivering Joseph to the pharaoh, Joseph Interpreting the Pharaoh's dream, The Pharaoh Paying him Honour, Jacob Sends His Sons to Egypt and Joseph Recognizes His Brothers and Returns Home.

Ghiberti combined two accounts of the story of Abraham from the Book of Genesis. At the lower left is the story found in Genesis 18:2-10; a time when three men (Ghiberti interpreted them as heavenly beings with wings) came to Abraham. Sarah is at the doorway of their tent while Abraham is kneeling before the men with a pan of water with which they may wash their feet. The men tell him his wife, Sarah, will have a son. Ghiberti’s narrative composition continues with images from Genesis 22:3-13; the sacrifice of Isaac. At the lower center is a donkey and to its right are Abraham’s two servants who wait while he and Isaac go to a higher level of the mountain. Above them, Isaac is kneeling on an altar and Abraham has raised his knife. An angel has arrived just in time to hold back the knife and stop him from killing his son. Behind the feet of Abraham is a ram caught in a thicket; it will be sacrificed in place of Isaac.

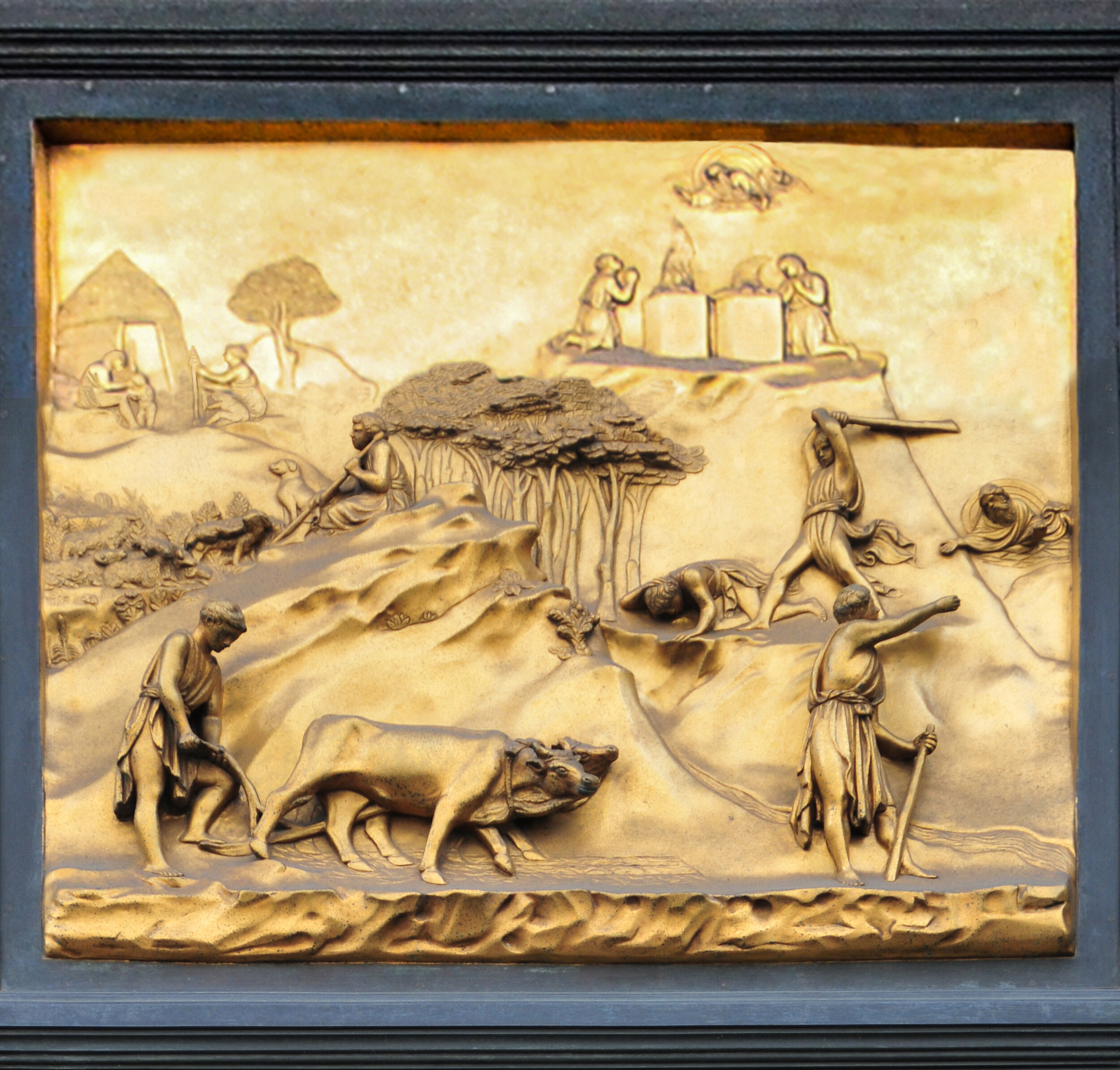

The panel has a left to right motion, beginning with Adam and Eve in the upper left, while Abel tends to his flock in the middle left and Cain plows his fields. At the top and towards the right Cain and Abel make their sacrifices to God. Just below that we see the murder, in the midst of Cain's attack on Abel. Just below that Cain appears again to receive the curse or mark from God who appears on the far right. It is quite remarkable that Ghiberti achieved such complex use of space and managed to clearly depict the story. However his skill in metalwork is even more remarkable. He makes the metal soft and hard at the same time, especially noticeable in the rock formations that take up the center of the panel; he conveys their hardness, but they appear flowing and soft as well. He creates a different effect altogether in the leaves of the trees, which are molded quite rigidly, but only to show their density and fineness. Ghiberti's molding of musculature is also incredibly skillful, as is the way he depicts Cain's pair of oxen, a technique that was still being worked out in the fifteenth century.

The designer and original architect for the Cathedral was Arnolfo di Cambia (1245-1310), the builder of both the Palazzo Vecchio and the city’s massive new fortifications. Filippo Brunelleschi grew up in Florence nearby the Santa Maria del Fiore and watched the cathedral being built. The foundation stone for the Cathedral had been laid September 8, 1296, but the Cathedral was not structurally completed and consecrated by Pope Eugenius IV until 1436, (140 years later). Even then it was not completed until May 27, 1471, when the gold ball designed by Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435 – 1488) was placed on top of the lantern of the dome.

A bust of Arnolfo di Cambio designer and first capomaestro of the San Maria del Fiore seen looking at his floor plan for Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedra. The bust is now located in the Museo dell’Opera del Museo on the Piazza del Duomo. After Arnolfo died in 1302, work on the cathedral slowed for almost 50 years. When the relics of Saint Zenobius were discovered in 1330 in Santa Reparata, the project gained a new impetus. In 1331, the Arte della Lana, the guild of wool merchants, took over patronage for the construction of the cathedral and in 1334 appointed Giotto to oversee the work. Assisted by Andrea Pisano, Giotto continued di Cambio's design. His major accomplishment was the building of the campanile. When Giotto died on 8 January 1337, Andrea Pisano continued the building until work was halted due to the Black Death in 1348.

Construction of the Cathedral of S. Maria del Fiore had progressed so well by 1300 that the Florentine city council authorized a lifetime tax exemption for its founding architect, Arnolfo di Cambio. Arnolfo was also the first capomaestro (artistic director and chief builder), a position later held by Brunelleschi while he was building the dome. Although di Cambio was the original architect, the design of the Florence Cathedral is generally regarded as collective in authorship due to the changes made during construction, repair and refurbishment over the years since his death, e.g., by Francesco Talenti.

In later life Arnolfo di Cambio returned to Florence (1296) and embarked on the ambitious project for the façade of the Duomo until his death. It is known from paintings, a drawing and descriptions, that he created sculptures for the facade highlighting episodes from the childhood of Christ and the life of Mary (above), a Virgin and Child (below), and statues of prophets and saints, including Pope Boniface VIII (below). Arnolfo arranged the façade so as to introduce the statues in niches, thus covering the walls of the lower parts.

Arnolfo made the statue to be placed on the facade he designed for the Cathedral. The term dormition expresses the belief that the Virgin died without suffering, in a state of spiritual peace. It is a great feast of the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches which celebrates the “falling asleep” (death) of Mary the Theotokos (“Mother of God” literally translated as God-bearer) and her being taken up into heaven (bodily assumption).

Arnolfo di Cambio balances the divine and human in the Madonna and Child Enthroned, also known as the Madonna of the Glass Eyes (1296). Madonna, the mother of Jesus, sits still on the throne holding baby Jesus on her knee and looks out afar. The now blank eyes of Jesus would have had painted pupils, but these would not have been as realistic and humanized as the glass eyes of Madonna. Arnolfo represents the baby Jesus with an adult-look in a gesture of blessing to emphasize his divinity. Because mostly marble sculptures before the time of Michelangelo are painted or partially painted, Madonna of the Glass Eyes would also initially, at least partially, have been painted by Arnolfo di Cambio to add the realism of the sculpture.

Pope Boniface VIII (born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – d. 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. Boniface VIII put forward some of the strongest claims of any pope to temporal as well as spiritual power. He involved himself often with foreign affairs, including in France, Sicily, Italy and the First War of Scottish Independence. These views, and his chronic intervention in "temporal" affairs, led to many bitter quarrels with Albert I of Germany and Philip IV of France. Boniface was the infamous pope who began the practice of selling indulgences to fill church coffers. Dante Alighieri placed the pope in the Eighth Circle of Hell in his Divine Comedy, among the simoniacs (the buying or selling of ecclesiastical privileges).

Giotto's sketch is for an ornate building in the Gothic style that accords with the imagined buildings of his earlier paintings. His lower section includes colored marble - white, green, pink and red predominantly - organized in geometric patterns. His design is complemented with a series of sculptural reliefs, designed by Giotto and executed by Andreas Pisano and other Florentine masters (including Donatello and Luca Della Robbia). Taken as a whole, the relief cycle represents a celebration of knowledge and thinking and charts the development of civilization through a series of panels. Collectively the reliefs (relievos) convey the idea that exploration, and learning through technology and theology, had made mankind worthy (potentially) of divine redemption.

The Campanile, 288’ tall and approximately 49’ in breadth, is the most eloquent example of 14th century Gothic architecture in Florence. By the time Giotto died he had completed only the first part of his bell tower, up to the hexagonal panels which form a kind of figurative narrative carved by Andrea Pisano to Giotto's design, and to the reliefs (formerly on a blue ground) by Andrea Pisano and Luca della Robbia. On the strength of his contribution to the cathedral's design, Giotto joined Brunelleschi (designer of the cathedral's dome) and Alberti (author of the first printed book on architecture "De re aedifcatoria", 1450) as one of the founding fathers of Renaissance architecture.

In 1334 Giotto was appointed chief architect to Florence Cathedral, of which the Campanile bears his name, but was not completed to his design. When Giotto took on the project, he was determined to remain faithful to the polychrome style that Arnolfo di Cambio employed in the rest of the cathedral—in addition to his own painterly aesthetic. Most noticeably is the geometric arrangement of different colored marble. Giotto imported material from the surrounding towns, including white marble from Carrara, green marble from Prato, and red marble from Siena.

Giotto is considered the most important Italian painter of the 14th century, credited with giving a new value to the human figure and its relationship with space. Giotto's depiction of the Virgin and Child as a human mother and child, as well as divine beings, was an important influence for later Renaissance artists, especially figures such as Filippo Lippi, tutor to Botticelli, whose images of the Madonna and Child develop the human element of the scene, eventually reducing the figures' gold halos to simple symbolic rings.

The painting is also notable for the clear sense of anatomical realism with which the figures are depicted. In previous eras, the anatomy of the figures beneath their clothes was generally not closely attended to, where Giotto takes care to suggest the human fleshliness of the Virgin and the baby Jesus. This is particularly highlighted through the subtle representation of Mary's knee and breasts through the fabric of her clothes, as well as the baby's body in its translucent robe.

Giotto's Crucifix in the church of Santa Maria Novella is a tempera painting that was commissioned by Dominican priests; it is the oldest major artwork in the church. The painting has extraordinary beauty that lies in the realism of the figure. Giotto focuses on the pathos of the Crucifixion scene and thus encourages the viewer to empathize with Christ's suffering. In contrast to earlier representations of Christ on the Cross, such as those by his teacher Cimabue, Giotto emphasizes the earthly heaviness of the body: the head sinks deeply forward and the almost plump body sags. The human side of the Son of God is made clear. Mary and John look down sorrowfully from the horizontal ends of the cross at the dead Lord. Giotto is revered as the father of European painting and the first of the great Italian masters. In The Divine Comedy, Dante acknowledged the greatness of his living contemporary through the words of a painter in Purgatorio (XI, 94–96): "Cimabue believed that he held the field/In painting, and now Giotto has the cry,/ So the fame of the former is obscure."

This picture shows the six of the hexagons designed by Giotti that are on the south side of the campanile, from left to right: “Gionitus, the inventor of astronomy:” Collaborator of Andrea Pisano (Master of Armor), 1334-1336; “Architecture,” Collaborator of Andrea Pisano (Master of Armor), 1334-1336; “Medicine,” Nino Pisano, 1334-36; “Hunting,” Andrea Pisano, 1334-1336; “Textile Production,” Andrea Pisano, 1334-36. [the woman on the right can perhaps be identified as Minerva, the inventor of weaving]; and “Phoroneus, inventor of law,” Nino Pisano, 1334-36. [Phoroneus was believed to have arbitrated a dispute between Hera and Poseidon.]

As a result of the work and guidance of Giotto and Pisano, at the base of the Campanile there is a remarkable set of 54 reliefs -- 26 hexagonal and 28 rhomboid. This bas relief "Euclid and Pythagoras" or "Geometry and Arithmetic," now in the Museo dell’Opera, was preserved from the north side of the lower basement of the campanile (bell tower); a copy is on the Campanile.

“Orpheus or Music” from the north side of the campanile (bell tower) lower basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

This original bas relief of "Plato and Aristotle" is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

Phidias (480-430 B.C) is often credited as the main instigator of the Classical Greek sculptural design and is consider one of the greatest of all ancient Greek sculptors. His Statue of Zeus at Olympia was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The relief was originally placed on the east side, but the relief was moved to the north side for the front door widening to the bell tower. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

Nino Pisano was an Italian sculptor, the son of Andrea Pisano. He collaborated with his father in sculptures for the churches of San Zanipolo at Venice and in Santa Caterina at Pisa, and provided some panels, such as this, for the bell tower of Santa Maria del Fiore. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the east side of the campanile.

"Agricoltura" from the east side of the campanile (bell tower), lower basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile..

"Navigation" from the east side of the campanile, the lower basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile..

"Creation of Adam" from the west side of the campanile. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile..

"Creation of Eve" from the west side of the campanile, lower basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

The city of Florence has proudly carried the Giglio of Florence on her coat of arms for almost a thousand years. The origin of the ubiquitous lily symbol however is even more ancient and can be traced back to the ruling class of the Roman Empire. This beautiful white flower was first applied to the city’s coat of arms in the 11th century; it was white on a red background. After the bloody battle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, which ended in 1250 with a victory for the Guelphs, they switched the colors as a sign of their power, thus creating the famous symbol of the red giglio on a white background.

Cacus lived in a cave in Italy on the future site of Rome. To the horror of nearby inhabitants, Cacus lived on human flesh and would nail the heads of victims to the doors of his cave. According to Evander, Hercules stopped to pasture the cattle he had stolen from Geryon near Cacus' lair. As Hercules slept, the monster stole four bulls and four cows by dragging them by their tails, so as to leave a trail in the wrong direction. When Hercules awoke and made to leave, the remaining herd made plaintive noises towards the cave, and a single cow lowed in reply. Angered, Hercules stormed towards the cave. Cacus attacked Hercules by spewing fire and smoke. Eventually, Hercules leapt into the cave, aiming for the area where the smoke was heaviest. Hercules grabbed Cacus and strangled the monster. According to Virgil in Book VIII of the Aeneid, Hercules grasped Cacus so tightly that Cacus' eyes popped out and there was no blood left in his throat.

Gino Micheli worked under the direction of Andrea Pisano between 1318 and 1323 and 1337 and 1341. “Matrimonio” was taken from the north side of the bell tower, upper basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

"Geometry" from the east side of the campanile, upper basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo and a copy is on the Campanile.

“Music” is one of the seven Liberal Arts among the 24 lozenges with bas relief on the campanile. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

"Astronomia" from the east side of the campanile, upper basement. This original bas relief is now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

Andrea Pisano, who was already famous for his South Doors of the Baptistry, built the next three sections of the Campanile. He first added the next level fascia, this time decorated with lozenge-shaped panels (1347–1341). He then built two more levels, each with 16 niches, four niches on each side. Statues were placed in the first level but the second row of niches are empty. Construction came to a halt in 1348, year of the disastrous Black Death. By 1352 the population of Florence had dropped to less than half of what it had been at the start of 1348. Almost 60,000 people living in the city had died, and those who did not die, fled to the countryside in large numbers, leading to further depopulation of the city.

Andrea Pisano replaced the bas-reliefs planned for the second level with sixteen niches, four on each side, designed to contain figures of the Kings and Sibyls (female prophets or oracles) and statues of the Patriarchs and Prophets. Those pictured here include from left to right: “The Beardless Prophet” by Donatello (probably a portrait of his friend, the architect Filippo Brunelleschi); “The Bearded Prophet” by Nanni di Bartolo; “The Sacrifice of Isaac” by Donatello; and “Il Pensatore” (The Thinker) by Donatello. The originals of all these sculptures, created between 1408-1421, are now kept in the Opera Museum for conservation purposes.

According to the Hebrew Bible, God commands Abraham to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice. After Isaac is bound to an altar, a messenger from God stops Abraham before the sacrifice finishes, saying "now I know you fear God." Abraham looks up and sees a ram and sacrifices it instead of Isaac. The other central theme in the Abraham story is God's test of his obedience. A copy of this statue is located on the campanile (3rd for left, above), on second level from the bottom.

“The Prophets” Donatello carved for the east side of Florence Campanile date from between 1415 and 1436. Pictured above, “Il Pensatore” (marble, ca. 1419-1420, 1.94 m height, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence) represents a milestone in realism, including a study in human thoughts and character. His attitude conveys thinking: the right hand under the chin and his slightly forward position seem to emphasize a contemplative attitude.

The Prophet Habakkuk statue was originally located on the north side of the Campanile. In Donatello’s Habakkuk the rendering of realism reached one of its highest points and it is recognized as one of the most important marble sculptures of the 15th century. Habakkuk’s figure appears skinny and bony under his rough robe that resembles a toga; his right hand clutches the strap and the rolled top of a scroll; his bald head is curved, left intentionally rough. While intended to represent a tormented and emaciated prophet, it is probably a portrait of Giovanni Chiericini, an enemy of the Medicis. This statue was Donatello’s favorite, and in his writings Vasari claimed Donatello is said to have shouted “speak, damn you, speak, or get the plague!!” at the marble as he was carving it. According to scripture, Habakkuk was saddened by the rampant injustice and violence occurring around him, and he was puzzled by God’s toleration of it. In his questioning of God, the prophet asks, “Why do you make me look at injustice? Why do you tolerate wrongdoing? Destruction and violence are before me; there is strife, and conflict abounds” (Habakkuk 1:3).

Francesco Talenti, Master of the Works from 1348 to 1359, completed the bell tower in 1359. In the 1350s he completed the the third and fourth stories of Giotto's Campanile set with eight windows (two on each side) and each of these is split with twisted Gothic columns. Inside the open windows on the three stories are seven bells, cast between 1705-1956. In addition, instead of a spire, the architect Talenti built a large projecting terrace. Visitors can climb to the top of the Bell tower to the projecting terrace (414 steps) for a view of Florence.

As capomaestro of Santa Maria del Fiore, Talenti completed two doorways, the Porta dei Cornacchini and the Porta del Campanile, respectively in the north and south sides of the Cathedral. Talenti enlarged the Cathedral structure by redesigning the apses and prolonging the nave, making the church the largest ever built in Europe so far. He continued working at the Duomo (1351–64, 1366–8), building the nave and helping to finalize the design of the east end, including the octagon above which the dome would be built 70 years later by Brunelleschi. Francesco Talenti’s involvement with the decorations of the north portal date back to its second phase of development, i.e. in 1353-64 in which, under the direction of Talenti, the splayings, the archivolt and the cusp with the tondo at the center, and finally the last phase (around 1380) in which the column-bearing lions supporting the twisted columns and the tabernacle above the spire were positioned.

Although Arnolfo di Cambio (1240-1310) designed the Cathedral in 1296, construction on the dome did not start until 1420. The picture shows the finished Cathedral facade (center) with Brunelleschi’s dome (near rear left), Campanile (middle rt.), and section of the Baptistry (far rt.)

The door is adorned with scenes from the life of the Madonna.

The building of the cathedral had started in 1296 with the design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was completed in 1469 with the placing of Verrochio's copper ball atop the lantern. The original façade was completed in only its lower portion and then left unfinished and would remain so until the 19th century. It was dismantled in 1587– 1588 by the Medici court architect Bernardo Buontalenti, ordered by Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici, as it appeared totally outmoded in Renaissance times. In 1864, a competition held to design a new façade was won by Emilio De Fabris (1808–1883) in 1871. Work began in 1876 and was completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto's bell tower and the Baptistery. The whole façade is dedicated to the Mother of Christ.

There are 13 statues above the main portal to the Cathedral and below the circular “Rose Window” - including the central statue of the Madonna with Jesus on her left knee, created by Tito Sarocchi, and statues of the 12 Apostles. In the spaces between the top of the pilasters and the pediment are the five priests blowing their trumpets before the walls of Jericho. The tympanum contains a bas-relief of the Madonna, seated and surrounded by seraphims and the Gonfaloniere and Priors (Magistrates) of the Florentine Republic who ordered the building of the Cathedral, along with Pope Callixtus III, St. Catherine of Siena, and others. On top of the pilasters are Pope Leo the Great (Leo I, d. 461) and Pope Gregory VII (d. 1085), two very powerful Popes. At the very bottom of the photo, Pope Callixtus I (d. 222), and Pope Celestine I (d. 432) are under baldachins in the middle of the left pilaster, and in the middle of the right pilaster are St. Jerome (d. 420) and St. Bonaventure, also under baldachins.

This statue of Brunelleschi sits outside of the Duomo and features the architect of the dome gazing upwards at his magnificent creation, mechanical tool in hand. It is almost as if he is still pondering the problems of its construction and determined to provide their solutions. Filippo Brunelleschi died in 1446 and was given the great honor of being one of the only Florentines who was granted permission to be buried inside of Santa Maria del Fiore. The inscription on his tomb states “Here lies the body of the great ingenious man Filippo Brunelleschi of Florence”.

Brunelleschi completed the dome In sixteen years only. With less than one hundred skilled workers he built this absolute masterpiece of engineering, consisting of more than 4 million bricks, with an estimated total weight of around 28,000 tons, for an external diameter of 54.8 meters (179.9 ft.) and 116 meters (380.6 ft.) tall (the lantern that tops the dome is as high as a six-story building, and it’s made of 600 tons of white marble).

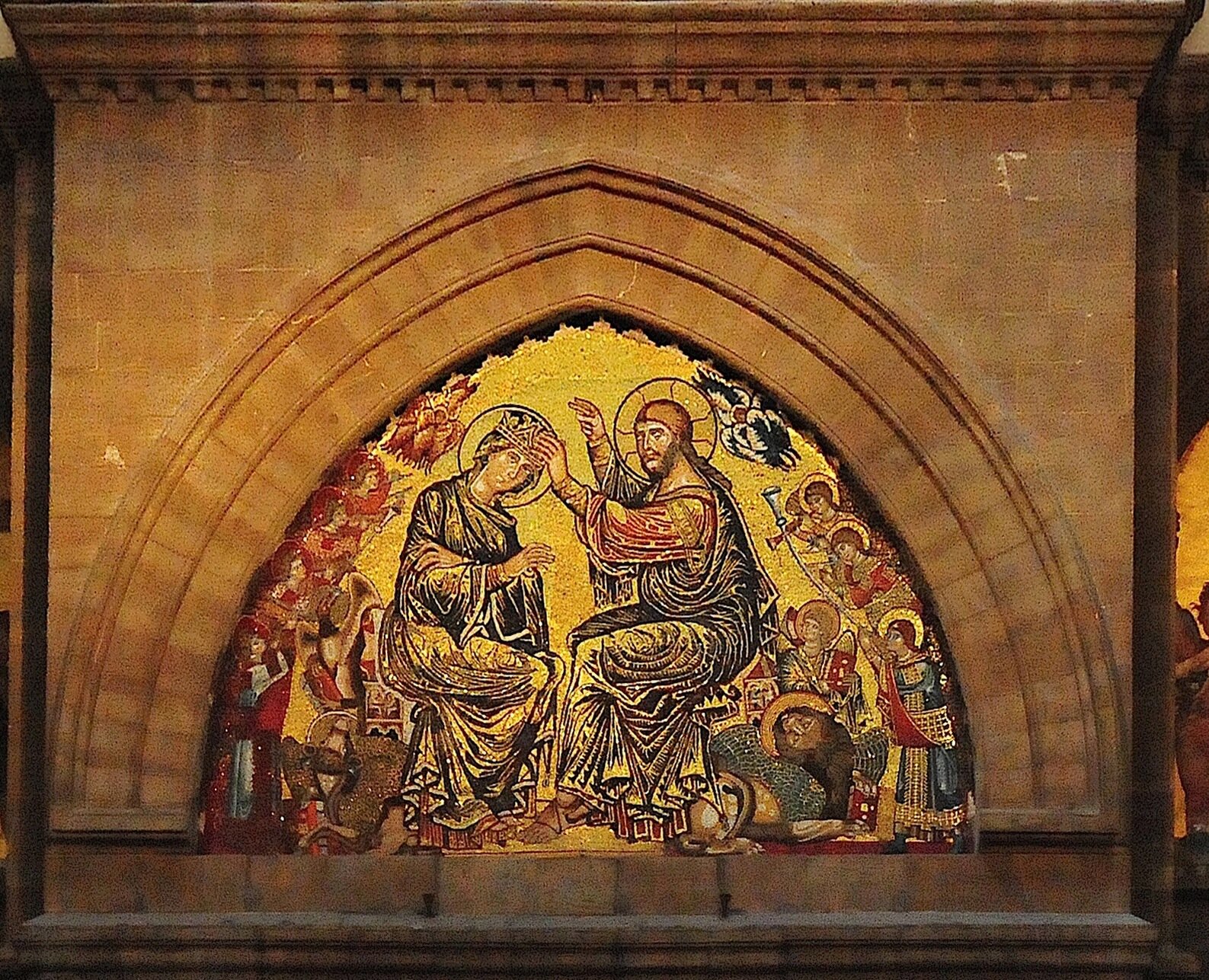

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s stained glass window (1405), Paolo Uccello’s unique Liturgical Clock, Gaddo Gaddi’s Coronation mosaic (1307), and Santi di Tito’s Music-Making Angels (1570s).

Thanks to Giorgio Vasari, we know that Paolo Uccello painted the clock facade in 1433 and that it measures almost seven feet in diameter. On the dial each of the 24 hours are painted counterclockwise in Roman numerals. At the center of a blue disc is a golden star. The radius with the ball on its tip rotates counterclockwise throughout the white areas arranged radially. They are inscribed in a square whose four corners are filled with four mysterious heads of men with halos appearing to look toward the center and down. According to some, they are prophets; for others, the four Evangelists.

Gaddo Gaddi was a painter and mosaicist of Florence in a gothic art style. Almost no works survive. He was the father of Taddeo Gaddi. He also completed mosaics on facade of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

In order to supervise the construction of Santa Maria del Fiore, the Florentine Republic founded, in 1296, the Fabbriceria, or Opera del Duomo. The emblem of the Opera—which can be translated as The Cathedral Works Administration—is the “Agnus Dei,” or Lamb of God, a crest derived from the Woolmakers' Guild, with the added initials OPA, meaning “per Opera,” that is, for the Opera: in this way homage was given to the Guild which almost entirely funded the construction of the cathedral.

The Gothic interior is vast and gives an empty impression. The dimensions of Santa Maria del Fiore are enormous: building area 89,340 square feet, length 502 feet, width 125 feet, width at the crossing 300 feet. The height of the arches in the aisles is 75 feet. The height of the dome is 375.7 feet. The relative bareness of the church corresponds with the austerity of religious life, as preached by Girolamo Savonarola, the Italian Christian preacher, reformer, and martyr, renowned for his clash with tyrannical rulers and a corrupt clergy. After the overthrow of the Medici in 1494, Savonarola was the sole leader of Florence, setting up a democratic republic.

Lighting a candle for someone is a way to both extend your prayers and show solidarity with the person the prayer is being made on behalf of. The faithful also light candles as a sign of gratitude to God for answered prayers. Also, burning votive candles are a common sight in most Catholic churches. These candles are seen as an offering that indicates we are seeking some favor from the Lord or the saint before which the votive is placed. (This information was taken from mercyhome.org website)

The canvas is divided, like the Commedia, into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Dante is placed in the center wearing a red robe and with the cap of the Florentines and a wreath of laurel on his head, and holding a volume of his poem La Divina Commedia. With his right hand he points to a procession of sinners being led down through the nine circles of Hell. Behind him in the center are the seven levels of the Mount of Purgatory, with Adam and Eve at the top standing in and representing the Earthly Paradise. Above them, the sun and moon and seven planets represent the Heavenly Paradise, while on the right is Dante’s home city of Florence, which is being illuminated by rays emanating from his poem, hence the title The Comedy Illuminating Florence. Michelino includes the recently completed Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, the Campanile or bell tower designed by Giotto, the Baptistry where Dante was baptized), the Bargello, and the Tower of Palazzo Vecchio.

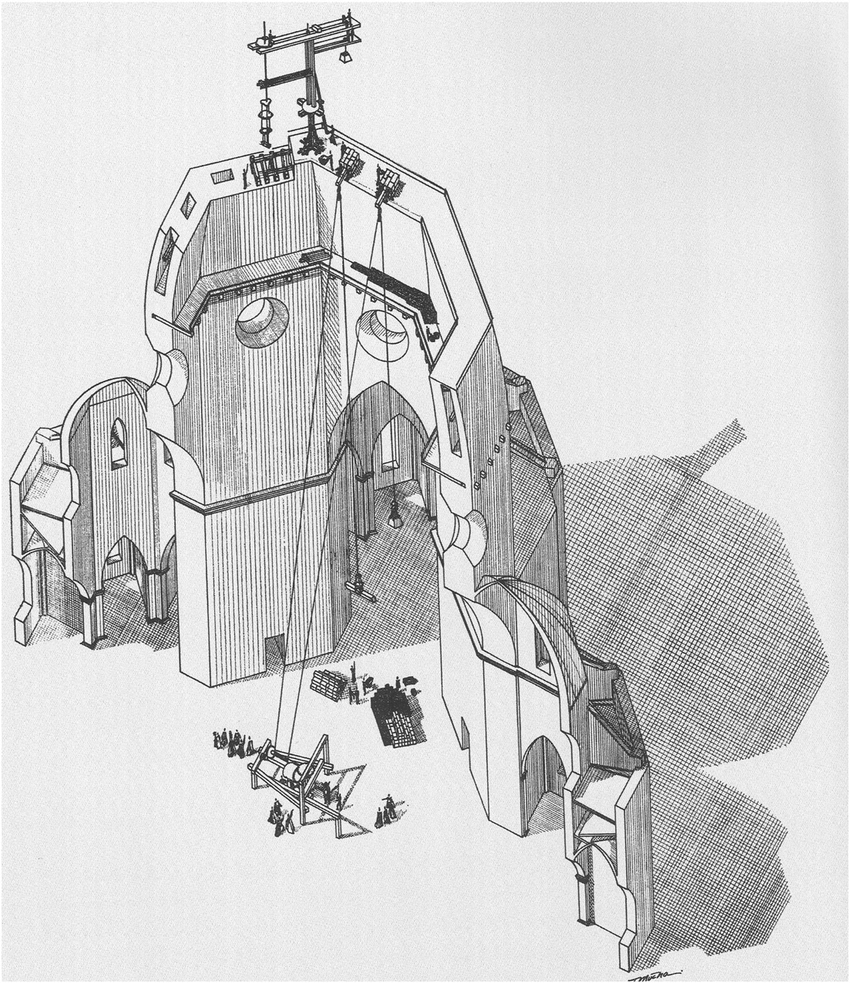

In order to raise the heavy marble up to the dome construction site, Brunelleschi invented the ox-hoist (1420-21). Before the dome was completed in 1436, the hoist would raise aloft marble, brick, stone, and mortar weighing an estimated 70 million pounds. The oxen walking in a circle, always in the same direction, made thousands of revolutions over the next dozen years lifting the materials up to the level of construction; they could raise a 1,000 pounds up to 200 feet in approximately 13 minutes.

Brunelleschi invented an ox-driven hoist that brought the tremendously heavy stones up to the level of construction. The hoist was gear driven with a clutch (using a three cogged wheel system) that allowed the hoist to be reversed without reversing the direction of the oxen. This technique had never been utilized before. The platforms for the workers were cantilevered from the walls of the dome and pockets were built in the walls to support these platforms. The accuracy of these pockets is remarkable, and it is believed that the platforms needed to be accurate and level so that the geometry of the dome could be ascertained by chains and string lines that were used to guide the masons in laying brick.

It was the Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici who had the idea to paint the dome’s interior. In 1572, (136 years after its completion) he commissioned Giorgio Vasari to paint frescoes on the dome of the Florence cathedral. When Vasari died in 1574, two months after the death of Cosimo I, he had only carried out one third of the work. Federico Zuccari, was hired to complete the work. Zuccari’s painting method was weak in quality but of great effect, a technique he learned to use for theatrical backdrops. He portrayed a lively gallery of contemporary personalities among the Elect: his Medici patrons, the Emperor, the King of France, Vasari, Borghini, Giambologna, other artists, and even himself as well as many of his friends and relatives.

Once Brunelleschi had finished the dome, the cathedral was structurally complete, minus the lantern, and Pope Eugenius IV, who was living at the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, consecrated Santa Maria del Fiore on March 25, 1436 — the feast day of the Annunciation and the first day of the Florentine new year. The Museo dell’Opera del Duomo is on the Piazza del Duomo, a three minute walk from the Cathedral; it contains many original statues and bas reliefs that were originally in or on the Cathedral.

The Opera del Duomo, also known as the "OPA", is the the Cathedral Workshop or "works commission" and was founded by the Republic of Florence in 1296 to oversee the construction of the new Cathedral and its bell tower. Since then, the main task for the Opera del Duomo has been to conserve these monuments - including the Baptistery of San Giovanni. In 1891, the Museum was founded to house the works of art which, through the course of the centuries, had been removed from the Duomo and the Baptistery. The Museo is comprised of 64,583 sq. ft. of showroom space, more than 750 works of art, a little more than 720 years of service by the commission (OPA), set in 25 rooms with a floor plan on 3 levels.

The Arte della Lana was the wool guild of Florence during the late Middle Ages and in the Renaissance and was nominally responsible for the building and decoration of the most important edifice in the city, namely the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. Its coat of arms is an Agnus Dei, lamb of God, an emblem to be found in various representations within and without the building. In the Agnus Dei symbol, the lamb was used to symbolize innocence and was also a sacrificial animal. The Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God, is an ancient symbol of Christ and His sacrifice. Standing with a banner, the lamb represents the risen Christ triumphant over death.

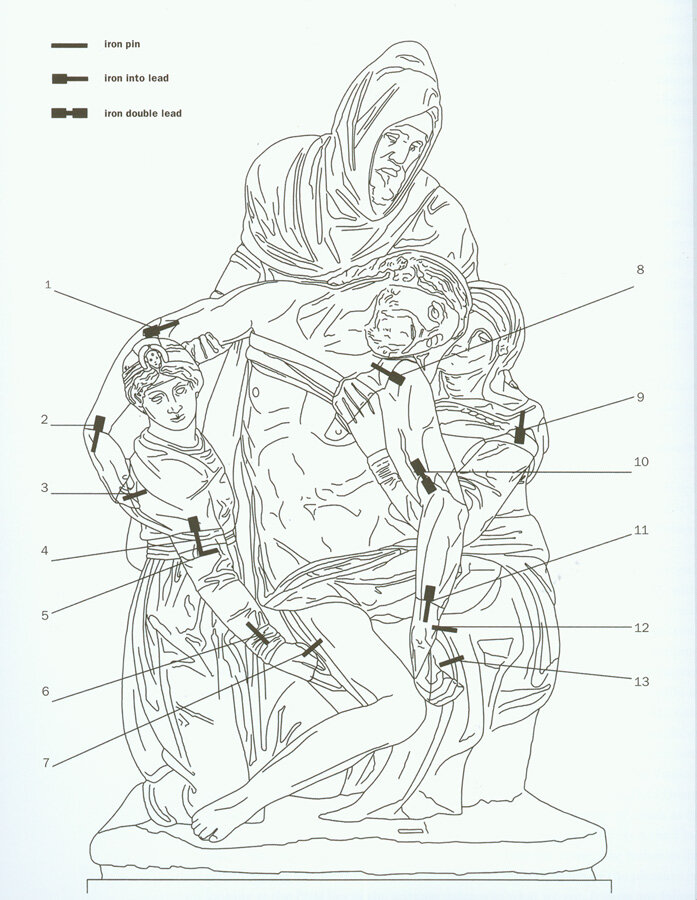

The four figures in this Florentine Pieta, the dead body of Jesus Christ, newly taken down from the Cross, Nicodemus, to whom the artist bestowed his own features, Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary are carved from a single block of marble that measures 7.4 feet tall and weighs some 5,952 pounds. Michelangelo was unhappy with the quality of the marble that came from the Seravezza quarries, which were owned by the Medici, because it revealed sudden veining and minute cracks difficult to detect from the surface. Vasari (1511-1574), gave several reasons why Michelangelo might destroy the Florentine Pieta: "...Either because of defects in the marble, or because the stone was so hard that the chisel often struck sparks, or because he was too severe a judge of his own work and could never be content with anything he did.”

A recent 2019-2021 restoration of the Florentine Pieta confirmed that the block used for the Pietà was indeed flawed. Numerous small inclusions of pyrite were discovered, and they most certainly would have caused sparks when hit with a chisel; the presence of numerous minute cracks, particularly on the back and front of the base, suggest that Michelangelo may well have encountered them when carving Christ and the Virgin's left arms and was forced to stop working on it. According to Vasari, ”…a piece had broken off the arm of the Madonna. This and a vein which appeared in the marble had caused him infinite trouble and had driven him out of patience.” According to Vasari, “Michelangelo often said that, if he were compelled to satisfy himself, he should show little or nothing. The reason is obvious: he had attained such knowledge in art that the slightest error could not exist without his immediate discovery of it….He often declared that this was the reason that the number of his finished works was so small."

Michelangelo gave the statue, with its various pieces, to his servant Antonio da Casteldurante who had it "restored" by Tiberio Calcagni. Tiberio Calcagni used models provided by Michelangelo himself on which to base his repairs. In his restoration, Calcagni reattached the limbs of Mary Magdalene, the Virgin's fingers, Christ's left nipple, Christ's left arm (as can be seen clearly in this picture) and elbow, and Christ's right arm and hand. The only thing that was not reattached was Christ's left leg. Castteldurante then sold the Pieta for 200 scudi to the banker Francesco Bandini.

Here you can see the results of the the damage and repair to Christ’s left arm and elbow, Mary’s left upper arm and the fingers on Mary’s left hand. Vasari noted that Michelangelo, at age 75, without commission, had worked tirelessly into the night with just a single candle to illuminate this work. After 8-10 years of working on it, Vasari claimed that Michelangelo attempted to destroy the work in a fit of frustration. However, the recent Opera del Duomo restorers found no sign of any hammer blows, unless, of course they were erased later by someone else. Others have suggested that Michelangelo removed the various parts with a chisel, perhaps with the intention of repurposing the marble.

The face of Nicodemus under the hood is considered to be a self-portrait of Michelangelo himself. Michelangelo started working on this sculpture when he was 73. The Florentine Pieta provides us with Michelangelo’s understanding of and preparation for his death at this point in his life. He wrote in a letter to Giorgio Vasari: “I have reached the twenty-fourth hour of my day, and…no project arises in my brain which has hath not the figure of death graven upon it.” In one of Michelangelo’s final poems, he confronts death and in some ways accepts and welcomes it: “Of death I am sure, but not of the time; Life is short and little remains before me; My senses are deleted, however I am bound for Heaven, and she prays that I go.”

The Brandini Pieta/Diposition” is my favorite Michelangelo Pieta due to its mature portrayal of physical death and its conveyance of the grief of death felt by the living. Vasari had proposed that this sculpture be placed on Michelangelo’s tomb, as Michelangelo had intended but these wishes were not carried out. In 1772 the sculpture was placed behind the high altar of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. It was sheltered in the Cathedral from 1942 to 1945 to protect it from war damage. In 1981, it was moved to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo both to prevent the massive influx of tourists from disturbing church services and for security reasons (the Vatican Pietà had been vandalised in 1972).

This sculpture group portrays the Virgin and St John the Evangelist holding up the lifeless body of Christ. The flattening of the relief might be connected to the piece of marble used, which was first carved in antiquity and originally an architectural element, as is clear from the decorative foliate and egg-and-dart motifs on the back. Purchased by the Italian State, thanks to a private donation, the sculpture came to the Galleria dell’Accademia in 1939. This unfinished Pietà was originally in a room beside the Santa Rosalia church in Palestrina and was owned by the Barberini family.

Michelangelo completed this work when he was only 24 years old. The sculpture, in Carrara marble, was moved to its current location, the first chapel on the north side after the entrance of St. Peter’s Basilica, in the 18th century. It is the only piece Michelangelo ever signed. Pieta means Pity or Compassion, and represents Mary sorrowfully contemplating the dead body of her son which she holds on her lap. Michelangelo made marble seem like flesh, and created complicated folds of drapery. It is an important work as it balances the Renaissance ideals of classical beauty with naturalism.

"The Penitent Magdalene" was carved from white poplar wood and records indicate Donatello was commissioned by the Baptistery of Florence. “The statue is a stunningly realistic interpretation of Magdalene’s character that differed from any other artist before him. It was common knowledge that Mary Magdalene had committed sin and lived a non-virtuous lifestyle. In Donatello's sculpture she appears penitent for her sins with an expression that pleads forgiveness. Donatello's Mary is also shockingly haggard…Donatello leads viewers to the assumption that her life of adultery and prostitution has stolen her beauty. She is deeply wrinkled and clothed in rags while her slightly open mouth reveals missing teeth. Donatello's interpretation of Mary is a staggering achievement that encapsulates the best of Renaissance naturalism.” (donatello.net)

Luca della Robbia's Cantoria for the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral was commissioned in 1431 and initially served as an organ loft. The Cantoria's ten large relief panels illustrate the text of Psalm 150, which is inscribed on its front in three sections and calls for the people to “Praise God…with sound …and dance…LET EVERY THING THAT HATH BREATH PRAISE THE LORD.

Women play the "cittern" (a lute-like instrument that is strummed or plucked) and sing in praise of God.

Women playing music and singing in praise of God with onlookers. The psalteries here are like our zithers or dulcimers with children at their feet mimicking their elders.

The children in motion below the trumpets are not holding up the trumpets but are making an arm arch for other children to dance under and through. A lively scene to show the joy of the trumpets' sound in praise of God.

Donatello was commissioned to create his Cantoria for the Duomo in Florence around 1433. The piece was part of a program that intended to beautify the interior of the Duomo. Donatello's work began shortly after the sculptor Luca della Robbia finished a piece of similar size and subject matter that decorated the area around the cathedral's organ. Donatello's Cantoria had the functional purpose of providing standing room for the choir and was nicknamed the "singing gallery." This enormous marble piece is composed of five large medievally styled columns. Behind the columns Donatello carved angelic dancing children in simple garments. These subjects are referred to as "putti" and were a common decorative element in both Donatello and Robbia's pieces for the Duomo.

Architecturally, Santa Maria Novella is one of the most important Gothic churches in Tuscany and was an integral part of Brunelleschi’s world. The facade is not only the oldest of all the churches in Florence but it is also the only church with its original, planned facade still in place today! This church was called Santa Maria Novella ('New') because it was built on the site of the 9th-century oratory of Santa Maria delle Vigne. When the site was assigned to the Dominican Order in 1221, they decided to build a new church and adjoining cloister. The church was designed by two Dominican friars, Fra Sisto Fiorentino and Fra Ristoro da Campi.

Building of Santa Maria Novella began in the mid-13th century (about 1276), and lasted around 80 years, ending under the supervision of Friar Iacopo Talenti with the completion of the Romanesque-Gothic bell tower and sacristy. Fra Jacopo was Magister lapidum ed edificoroum (master of stone building) of the convent and church of Santa Maria Novella from 1339 to 1362. Fra Jacopo was a brother of Francesco Talenti, who as a capo maestro of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral (1351–64, 1366–8) expanded the Cathedral’s size and finished its Campanile in 1359.

The Piazza di Santa Maria Novella was officially inaugurated in 1287 by Decree of the Republic Fiorentina and donated to the homonymous Basilica as its natural extension. The place soon became an important reference for the entire local community and beyond. The Piazza fronts the Basilica, the adjoining cloister, and chapterhouse, which contain a store of art treasures and funerary monuments. Especially famous are frescoes by masters of Gothic and early Renaissance. They were financed through the generosity of the most important Florentine families, who ensured themselves of funerary chapels on consecrated ground.

After the arrival of the Dominicans the Piazza Santa Maria Novella became in fact the scene of crowded religious sermons. Given the importance and the big affluence in Santa Maria Novella, they City of Florence started to celebrate events, games and traditional rides. The most important amongst these rides was the one so called the “Palio dei Cocchi” (a race with coaches like the Roman chariot), established by Cosimo I di Medici in 1563. The carriages (or Cocchi) used to race around two marble obelisks supported by four bronze tortoises (built by Giambologna) that bordered the highest points of the track. The game used to be played on June 23th, on St. John the Baptist eve, saint and patron of Florence. The four wooden chariots had four different colors (depending on the district represented): green, blue, red and white, each one pulled by two horses. After three elliptical laps around the pyramids, the race ended. The prize for the winner was a velvet fabric (or drape). [Opera Per Santa Maria Novella Magazine 5/17/2016]

Pope Eugenius IV (1383–1447), as the Catholic’s living symbol of Christ on earth, lived in Papal apartments located in the Dominican convent of Santa Maria Novella that were prepared for him after he had to flee Rome in 1434 due to a popular uprising in Rome led by the Colonna family. Workers had to be reassigned from the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral to prepare the Papal apartments, creating delays in the construction of the Cathedral dome. However, once Brunelleschi finished the dome, Pope Eugenius IV consecrated Santa Maria del Fiore on March 25, 1436 —the feast day of the Annunciation and the first day of the Florentine new year. In 1439 Santa Maria Novella was the scene of the Council of Florence, convoked by Eugenius IV to bring about the reunion of the Greek and Latin Churches.

Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai a wealthy Florentine wool merchant commissioned Leon Battista Alberti who completed the upper part of the church facade using the inlaid green marble of Prato, also called 'serpentino', and white marble (1456–1470). His contribution consists of a broad frieze decorated with squares, and the full upper part, including the four white-green pilasters and a round window, crowned by a pediment with the Dominican solar emblem, and flanked on both sides by enormous S-curved volutes. The four columns with Corinthian capitals on the lower part of the façade were also added. The pediment and the frieze are clearly inspired by antiquity.

One problem that Alberti had to solve in his design for Santa Maria Novella was the fact that the two levels of the church were of quite different heights. He solved this by tying them together visually with the use of ornate S-curved scrolls on either end. Alberti’s use of the scrolls in the upper part of the Basilica facade introduced a new design element that was without precedent in antiquity and solved a longstanding architectural problem of how to transfer from wide to narrow stories. The scrolls (or variations of them), found in churches all over Italy, all draw their origins from the design of this church. The façade that Alberti added is a perfect example of the harmony found in the arts in the early Italian Renaissance.

The Main Portal lunette contains the primary fresco that shows a Dominican Friar (Black Friar), identified as St. Thomas Aquinas, with angels in the foreground, and the procession for the Feast of Corpus Domini, leading to Santa Maria Novella in the background. Since the late 1200s, processions of the Feast of Corpus Domini in Florence always terminated at the Piazza di Santa Maria Novella, which was the largest public space in Florence at the time. Santa Maria Novella, the first great basilica in Florence, is the city's principal Dominican church.

The lunette and pediment above the left portal contains a fresco that references the Lombards, the Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin which, in the 6th through 8th centuries, controlled Italy and provided many of the bankers and other important families living in the area during the Middle Ages. All three of the portals were frescoed with scenes that refer to the feast and procession of the Corpus Domini, which had terminated at Santa Maria Novella since the late 1200s. The Lombard figure is presenting bread.

The lunette and pediment above the right portal contains a fresco that references a much older patriarchal figure, dressed in robes of the late Roman period. Due to the deterioration of the fresco it is difficult to tell what sort of food the patriarchal figure is presenting to the feast, but it seems to be some sort of flask. Just like the other Lombard-related figure this fresco is intended to represent the early heritage of the feast day of Corpus Domini.

Dominican nun Plautilla Nelli created this ground-breaking addition to the Last Supper genre. Nelli was a self-taught painter and innovator who ran an all woman artists' workshop out of the Santa Caterina convent. In 1568, she embarked on her most ambitious project, a monumental The Last Supper painting featuring life size depictions of Jesus and the twelve apostles. She was likely the first woman in the world history to paint this iconic scene. Nelli's large canvas is remarkable for its challenging composition, powerful brushstrokes, and adept treatment of anatomy at a time when women were banned from studying the scientific field. Her painting was likely a workshop collaboration, with Nelli executing the drawings and painting the heads shown in 3/4 profile. The work hangs in the SM Novella museum alongside masterpieces by Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Ghirlandaio.

Wall of the suggestive garden, which was in actual fact used in the 14th century as a burial ground, the so-called Cemetery of Plaona, can be seen on the righthand side of the Basilica. It once contained as many as 80 tombs placed underneath the typical Gothic sepulchre arches: in fact they gave the name to the street, Via degli Avelli (tombs), that connects Piazza Santa Maria Novella with Piazza Stazione. Painter Domenico Bigordi, better known as Ghirlandaio, was buried in one of these tombs in 1494, the third from the facade; the arch above it once contained a life-size portrait of him. Portraits of all the Bigordi family can be seen in the frescoes in the Main Chapel.

This Botticelli “Nativity Scene” is standard in terms of its content: the infant Christ, required to be at the centre of course, with Joseph the carpenter on one side, and the Virgin Mary on the other. They are within a semi-derelict cattle-shed, with a background of an ox and an ass, and while there are no attendant shepherds there is a small angelic figure. Botticelli does a fine job here but it does not have the greatness of his later paintings, e.g., Primavera (1482), The Birth of Venus (1486), Madonna of the Pomegranate (1487), a personal favorite, or his Mystic Nativity (1500).

From the entrance, looking up the nave of the Basilica one sees a bronze crucifix by the sculptor Giambologna (Giovanni da Bologna, 1529-1608) on the main altar. Behind the altar is the Tornabuoni Chapel by Domenico Ghirlandaio. The frescoes of this apsidal chapel represent a major example of chapel decoration at the end of the Quattrocento (14th century). The patron was the wealthy Giovanni Tornabuoni, the relative by marriage of the Medici, and in order to finish this work timely Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494) enlisted his whole workshop in the undertaking, including possibly a then 13-year-old apprentice called Michelangelo Buonarroti. The chapel’s vault contains the Evangelists. On the left wall Domenico frescoed the stories of Mary, while on the right the life of St. John the Baptist. In the lunette of the window wall is the Coronation of the Virgin.

The left window begins with Saint Dominic who holds lilies, above him Saint John the Baptist holds a cruciform staff, and, at the top, Saint Peter carries a book and keys.

The central section begins with the Miracle of the Snow. The legend tells that the Virgin appeared in a dream to Pope Liberius, asking for a church in her name. The following morning, despite it being August, snow fell, outlining the dimension of the church. Begun in 432, the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore is one of the most venerable in Rome. Above the Miracle is the Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple. Above that is the Assumption of the Virgin, who lets down her girdle to Saint Thomas, a reference to the tangibility of her physical assumption to heaven.

To the right, the row begins with Saint Thomas Aquinas wearing a star-studded robe and holding a sun of divine radiance, symbol of his inspired theology. Above him Saint Lawrence, a deacon in Rome, holds his grill, the symbol of his martyrdom. At the top is Saint Paul, a complement to Saint Peter on the left.

Ghirlandaio decorated the Tornabuoni Chapel vault (ceiling) with the four evangelists, St. John the Evangelist (bottom), St. Matthew (left), St. Luke (right) and St. Mark (top).

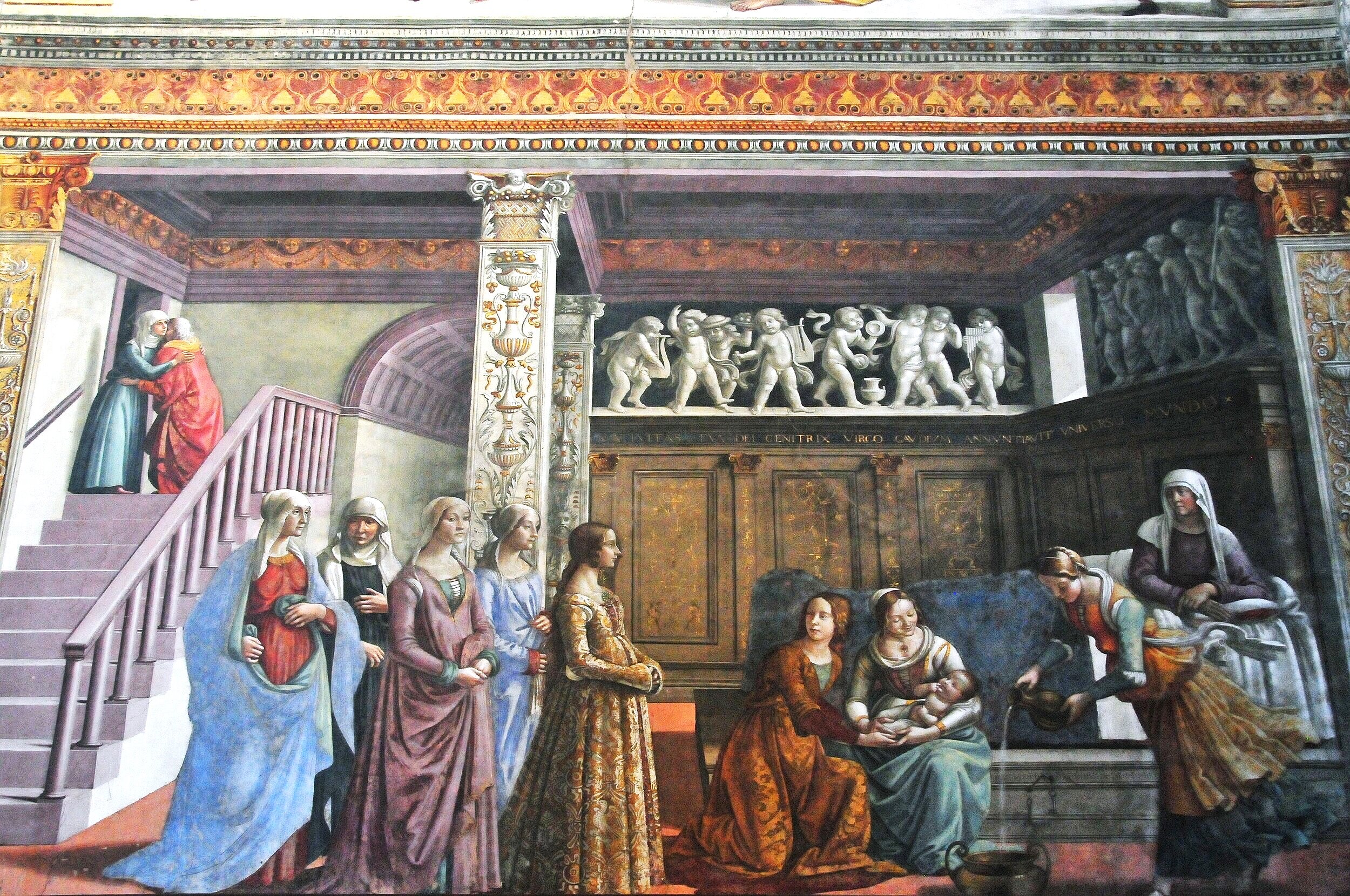

Ghirlandaio filled the Scenes from the Life of the Virgin and Scenes from the Life of the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence, with figures from the upper-class Florentine society of the time. On the right wall of the chapel the “Scenes from the Life of the Baptist, right to left: (bottom row) “The Apparition to Zachariah” and “The Visitation;” (row 2) “Birth of St. John” and “Zacharias Writes Down the Name of his Son;” (row 3) “Preaching of St. John the Baptist” and “Baptism of Christ:” and (top) “Herod’s Banquet.”

“The Visitation” portrays the meeting of Mary with the aged Elizabeth. The complex composition includes in the centre the key episode, the relevance of which is strengthened by the converging lines of a wall in perspective and a ravine in the background. Behind Elizabeth are two maidens, while on the two extremities are other groups of women. The group on the right include portraits of contemporaries: the first, in profile, is Giovanna degli Albizzi, who had married Giovanni Tornabuoni's son Lorenzo. The city is fanciful, but details like the tower of Florence's Palazzo Vecchio and the Santa Maria Novella campanile, as well as Rome's Colosseum are from real buildings. All the elements in this picture were explicitly required in Tornabuoni's contract with Ghirlandaio: the landscape, the city, the animals, the perspective, the portraits and the classical elements.

This scene is linked with that in the opposite wall, the Birth of the Virgin, with which it shares an element of composition having the bed placed symmetrically. Elizabeth is depicted on the bed in a calm and majestic posture, with a book in her left hand. As in the other scene, there are two nurses painted with brilliant colours to attract the watcher's attention. Three women, also in the foreground, are visiting Elizabeth. The first, luxuriously dressed, could be a relative of the Tornabuoni. Of the two other figures, the older is most likely Lucrezia Tornabuoni, Giovanni's sister, who had recently died. The maid entering from the right with a basket of fruit on her head resembles both one of the nymphs of Botticelli's Primavera and the Salome painted by Filippino Lippi in the Prato Cathedral. In a preparatory drawing now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin the maid is in fact Salome carrying the Baptist's head.

The scene of the baptism follows a traditional scheme: for example, the panel on the North Doors (1403-1424) of the Baptistry of St. John by Lorenzo Ghiberti showing St John pouring water over Christ’s head. Also notable is the figure of the kneeling man on the right, who is removing his shoes while looking with curiosity at the scene, while traditional portrayal is again seen with God giving his blessing between the angels, in the upper area, which is in a quasi-Late Gothic style.

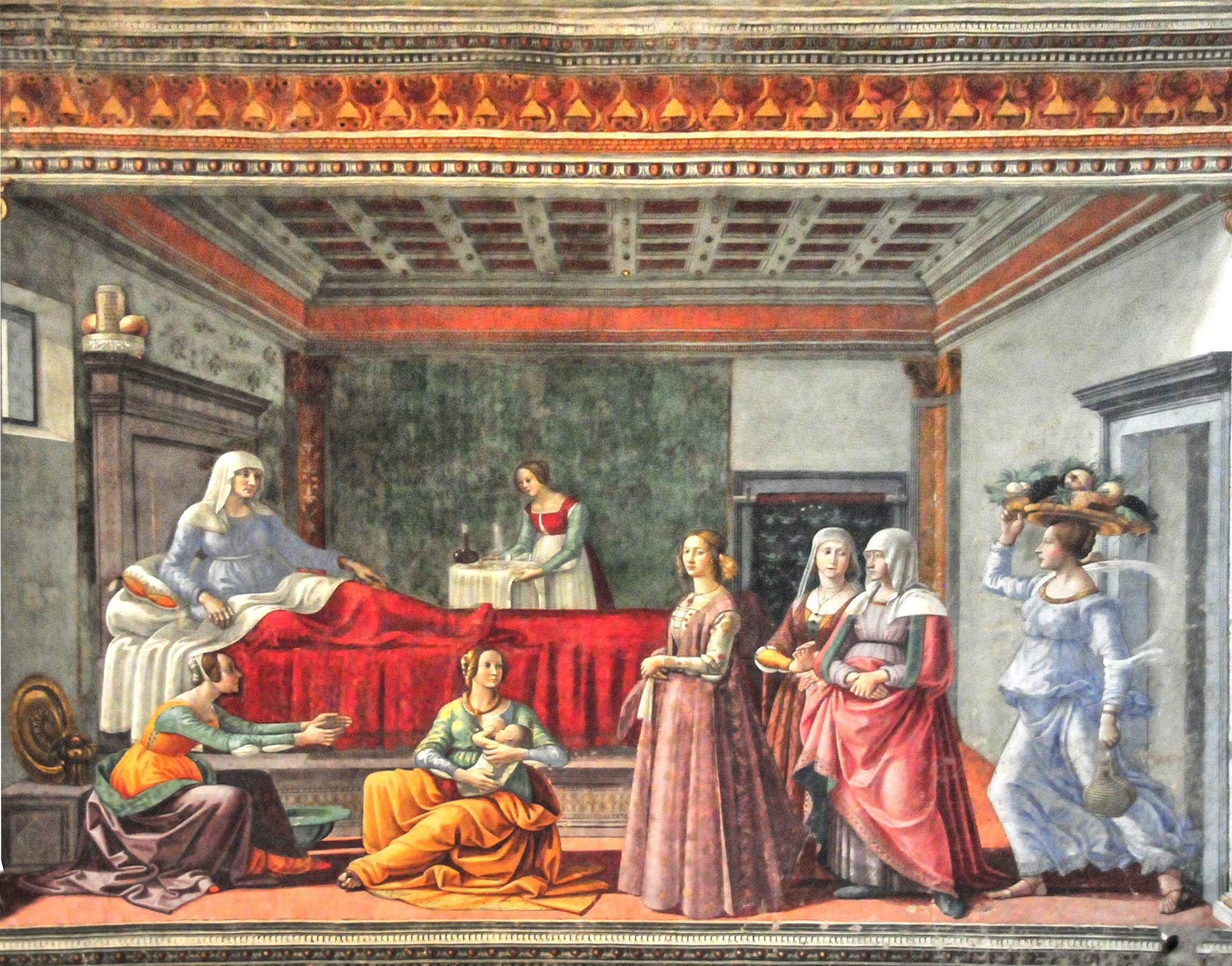

The “Nativity of Mary” is set in a luxurious room with inlaid wooden panelling surmounted by a frieze in bas-relief of music-making putti and a cornice of winged cherubs. To the right, St. Anne reclines in bed, while three young women prepare to bath the new-born Mary. The nurse who is pouring water into a basin is the only figure in the room to be moving rapidly. Her flowing robes and swirling scarf make her an iconic motif to be found in many paintings both by Ghirlandaio and other painters and sculptors of the period.

Several well-dressed Florentine ladies have come on a congratulatory visit. The first in the procession of noblewoman, portrayed in profile, is Ludovica, daughter of Giovanni Tornabuoni. The rendering of the magnificent women's clothes is particularly notable. The scene is considered one of the best executed in the chapel. Above the cabinets in the background is an inscription reading: "Your birth, oh Virgin Mother, announced joy to the whole universe."

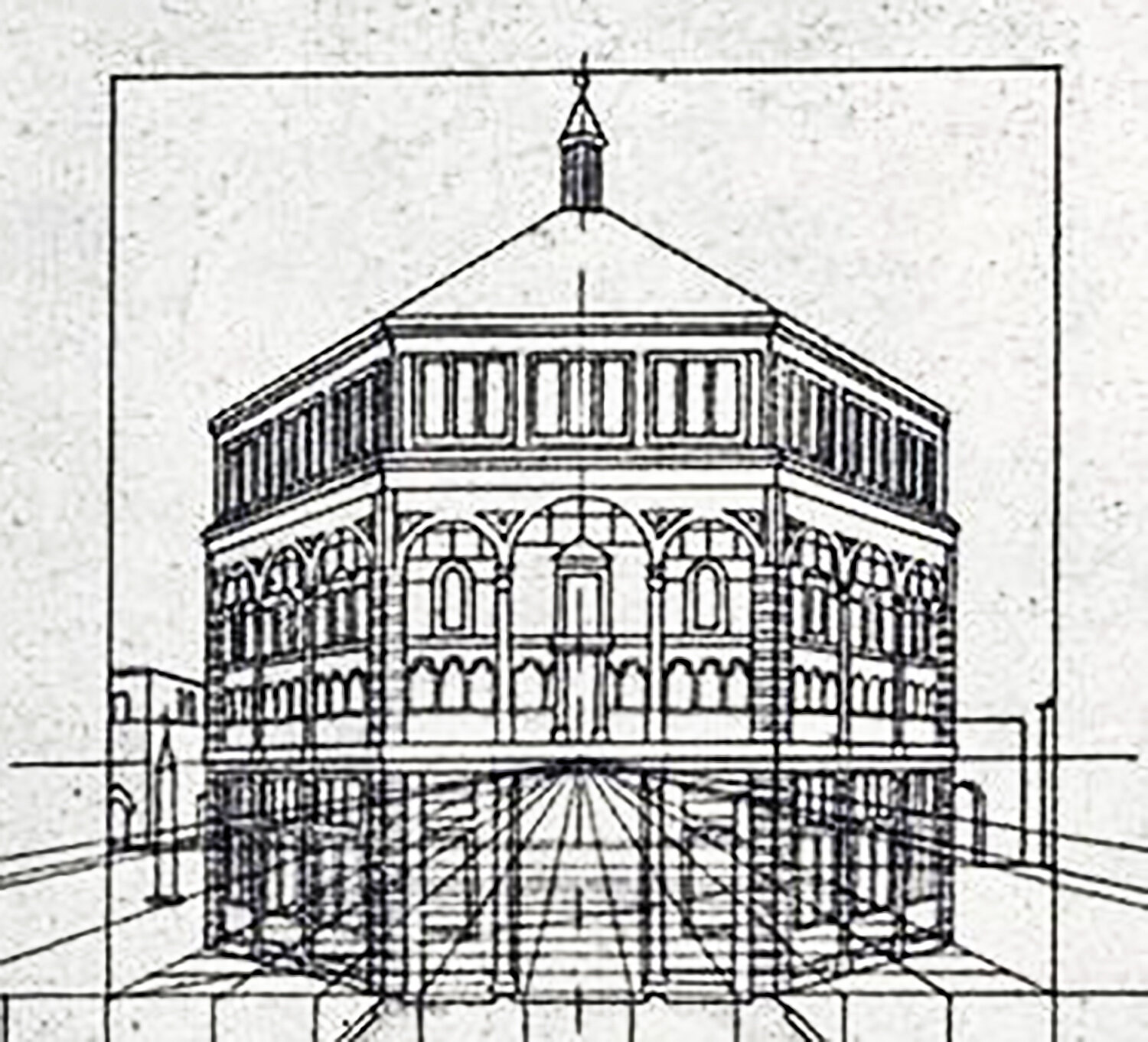

In the early 1400s, the Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi reintroduced a means of rendering the recession of space, called linear perspective. In Brunelleschi’s technique, lines appear to converge at a single fixed point in the distance. This produces a convincing depiction of spatial depth on a two-dimensional surface. Brunelleschi used this technique in a famous experiment. With the help of mirrors, he sketched the Baptistery in perfect perspective. He mathematically calculated the scale of objects to appear within a painting, in order to make them look realistic. This discovery of a mathematical system for representing three-dimensional objects and space on a two-dimensional surface was tremendously significant. Soon after Brunelleschi’s discovery, other artists employed this method of rendering perspective, with astonishing results.

Brunelleschi's mathematically based 3-dimensional representation of the Baptistry of St John on a two-dimensional surface from a Lost Painting of the Battistero di San Giovanni. Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Max-Planck-Institut. © 2006, SCALA, Florence / ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

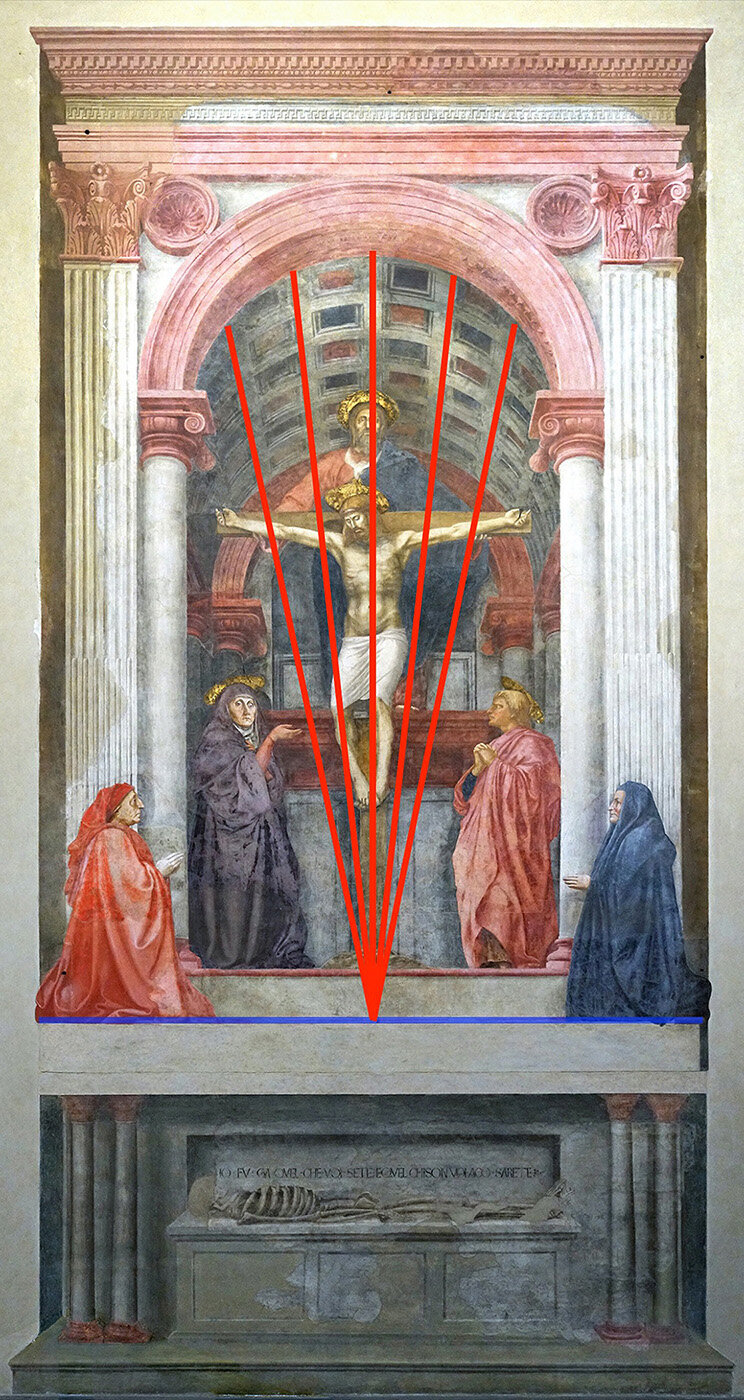

Masaccio, born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi's development of linear perspective in his art. Masaccio started by producing a rough drawing of the composition and perspective lines on the wall. The drawing was covered with fresh plaster for making the fresco. To ensure the precise transfer of the perspective lines from the sketch to the plaster, Masaccio inserted a nail in at the vanishing point under the base of the cross and attached strings to it, which he pressed in (or carved into) the plaster. The marks of the preparatory works are still visible.The orthogonals (lines that are perpendicular or that form right angles) can be seen in the edges of the coffers in the ceiling (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance). Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint, as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals, we would see that the vanishing point is on the ledge that the donors kneel on. As for the innovation of perspective in painting, Vasari wrote that "the most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is a barrel-shaped vaulting, drawn in perspective and divided into squares filled with rosettes, which are foreshortened and made to diminish so well that the wall appears to be pierced."

Masaccio presents the Trinity as Jesus on the cross, The Holy Spirit above his head in the form of a White Dove, and God the Father standing behind. Here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract, but as a man. A man who stands—his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and is capable of walking. In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives—but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man. Also, Masaccio echoes Giotto's depiction of the realistic suffering and bodily weight of Christ. These presentations are good indications of Humanism in the Renaissance. There is a cadaver tomb below the fresco that carries in Italian the epigram: "I was once what you are, and what I am you will become" (see picture below).