This room owes its name to the fire that broke out in the year 847 in the neighborhood in front of St. Peter's Basilica. The room was used in the time of Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) for the meetings of the highest court of the Holy See, the Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae (The Signature of Grace and Justice), presided over by the Pope. However, at the time of Leo X (pontiff from 1513 to1521) the room was used as a dining room and the task of frescoing the walls was assigned to Raphael who entrusted a large part of the work to his school. The work was completed between 1514 and 1517.

After Raphael was assigned to fresco it, Julius II died and the new Pope Leo X (pontiff from 1513 to 1521) decided to have him paint scenes related to the various popes who had had the same name: Leo III (Crowning of Charlemagne and Justification of Leo III) and Leo IV (Fire in the Borgo and the Battle of Ostia). Much of the frescoes in this room were developed by Raphael's students because the Master was engaged by other Papal commissions such as the Sistine tapestries. Six seated figures of emperors and sovereigns who are protectors of the church are shown in the monochromes below the paintings.

In 1508 Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) commissioned Pietro Vannucci, called the Perugino, to paint the ceiling of the room that at the time was used to host the meetings of the highest court of the Holy See, the Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae (The Signature of Grace and Justice), which was presided over by the pontiff. In concert with the room’s function, Perugino depicted in the four medallions: 1) the Most Holy Trinity, 2) the Creator enthroned among angels and cherubs, 3) Christ, as the Sun of Justice, Tempted by the Devil, and 4) Christ between Mercy and Justice.

As the last prophetic book of the Old Testament (515-445 B.C.). Malachi refers to the coming Messiah who will restore all things and usher in the Kingdom of God. In Malachi 4:2, we see the Messiah referred to as the "Sun of Justice", sometimes called the "Sun of Righteousness." The period of waiting for the Messiah was a period of long darkness; but though the night is long, eventually the sun peaks above the horizon, and eventually illuminates the entire earth under its brilliance. By depicting Christ standing between symbolic figures of Holiness and Evil, Perugino reminds us of our freedom to choose between the light and darkness, between good and evil. This is what I love about art – it transcends time, place, culture, etc. to inform us of the human condition; it informs us of our choices today.

In the fresco, Pope Leo III, born a commoner, is seen at trial on December 23 AD 800 during which he was brought face to face with the nobles, including the nephews of his predecessor Pope Hadrian I, who believed a commoner should not be Pope. They had accused him of misconduct, and an angry mob had threatened to gouge out his eyes and tear out his tongue. Pope Leo escaped and fled north to the city of Paderborn where he met with Charlemagne, whom he had previously asked for support. Charlemagne and his forces then escorted Leo III back to Rome. There, Charlemagne held a council with both Pope Leo and the pope’s enemies.

Pope Leo III is shown taking an oath of purgation - he swore that he was innocent of any crimes – while the Pope’s powerful supporter, Charlemagne, holding a crown, is watching seated on the upper left. As a result of this council, the Roman nobles who opposed Leo were banished. Then, two days later, on Christmas Day, 800 C.E., Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor of the Roman Empire. By crowning Charlemagne, the Pope Leo X gave the papacy and the church implicit authority over the empire, since with this act Leo set a precedent for crowning emperors, which subsequent popes would do throughout the reign of the Holy Roman Empire.

On the ceiling of the Room of the Fire in the Borgo, under which Raphael painted the The Coronation of Charlemagne (1516-17), Perugino depicted the Most Holy Trinity, the very essence of the Christian God. Showing in vertical continuation, above is the Father, holding the earth in his hand and surrounded by putti and angels, in the center Jesus incarnate, standing and glorious, surrounded by the kneeling Apostles, and below Christ, toward us, hovers the Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove.

The painting shows how Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III (pontiff from 795 to 816), the continuation of the Holy Trinity on earth, on Christmas Evening, 800. Behind Charlemagne, a child page holds the royal crown that he just took off to receive the imperial one. According to Giorgio Vasari (often called “the first art historian”), the child page holding the royal crown is a portrait of the infant Ippolito de’Midici, whose father died when he was only five (1516), and he was subsequently raised by his uncle, Pope Leo X, and his cousin, Giulio de' Medici.

It is suggested that the fresco refers to the Concordat of Bologna, negotiated, in 1515, between the Holy See (the universal government of the Catholic Church) and the kingdom of France, since Leo III is in fact a portrait of Leo X (head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States (1513 -1521) and Charlemagne a portrait of Francis I (King of France, 1515 - 1547). Amongst other matters, the Concordat of Bologna permitted the Pope (Leo X) to collect all the income that the Catholic Church made in France, while the King of France (Francis I), was confirmed in his right to tithe the clerics and to nominate appointments to benefice (archbishops, bishops, abbots and priors).

As Sol Justitiae (the Sun of Justice), Christ triumphs (within the mandorla of divinity) suspended between Justice, equipped with scales and sword, and Mercy, who stands at His right, toward whom He turns with a benign gesture and gaze.

The necklace on the chest of Justice is known as Solomon’s Knot, the sign named after the great King of Israel. On this sign there existed, since Mesopotamian antiquity, a very strong and complex symbolism, taken up by various peoples and reaching as far as Dante in the Divine Comedy. In the Middle Ages Solomon’s knot was used as an amulet to ward off evil and ensure justice. In Perugino’s fresco, the knot signifies the perfect equity of Justice.

The Fire in the Borgo celebrates the intercession of Leo IV, by whose grace a fire which spread through the Borgo, a popular section of Rome near the Basilica of St Peter, was extinguished. The event depicted happened in AD 847 and is documented in the "Liber Pontificalis" (a collection of early papal biographies). The scene is highly effective and demonstrates Raphael's skill as an illustrator, although it may have been executed largely by his pupils.

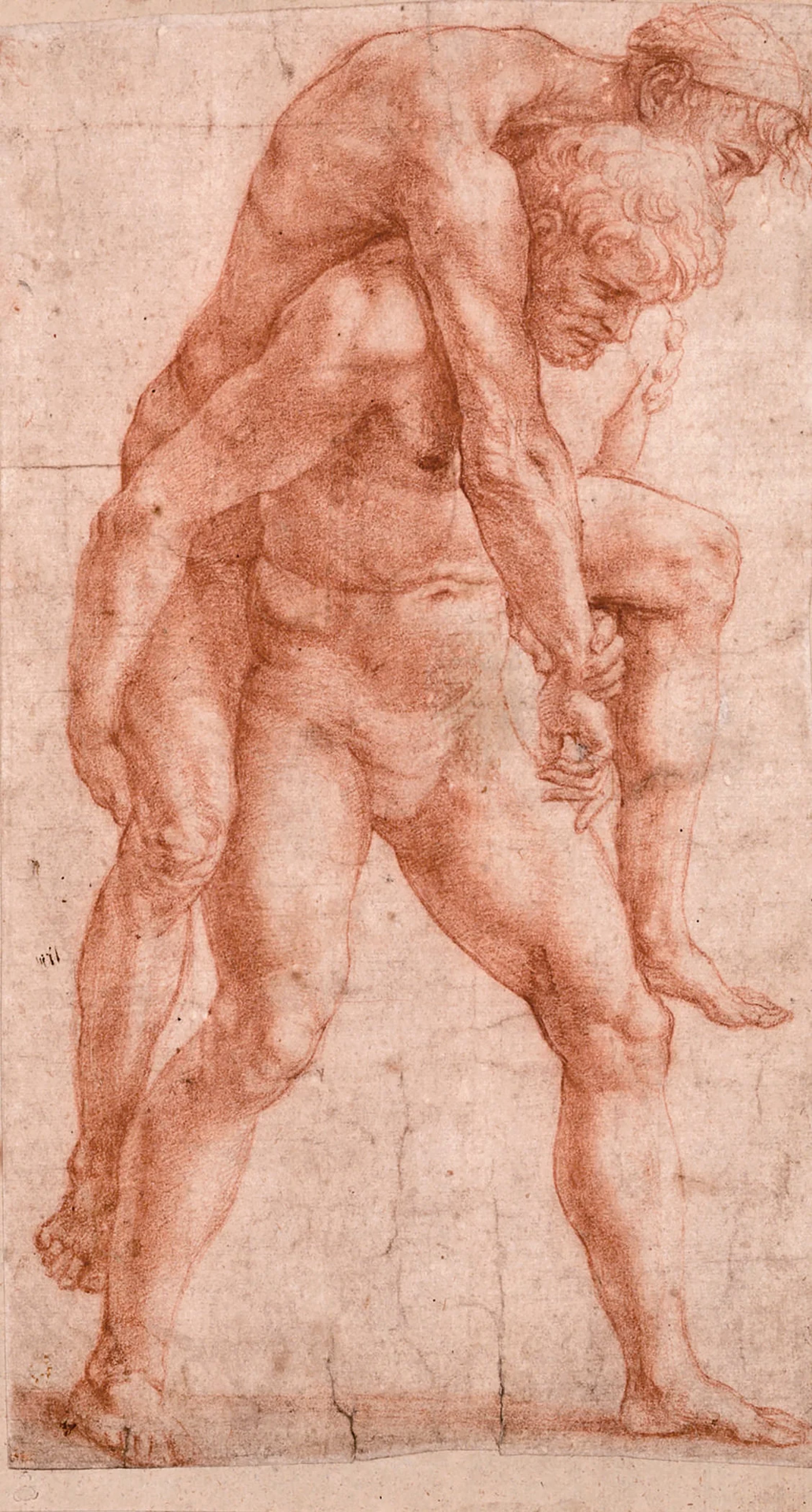

Raphael’s study of Aeneas carrying Anchises for The Fire in the Borgo, based on the episode of the Aeneid in which after a ten-year siege of Troy, the Greeks finally succeeded in overrunning the city by tricking the Trojans with the Trojan horse. As the city was being sacked, Aeneas, a Trojan prince carries his elderly father, Anchises, on his back from Troy.

Raphael may have designed the group in the left foreground of The Fire in the Borgo, made up of an old man on the shoulders of a young man, and a child, from the episode of the Aeneid in which Aeneas, a Trojan prince carries his elderly father, Anchises, on his back; who in turn carries his ancestors' ashes and household gods. Ascanius, Aeneas' son, follows close behind. Aeneas eventually leads his family to Latium in Italy, where he becomes an ancestor of the Roman people. Aeneas was considered a role model for his commitment to moral duty, both before the gods and before other men. Next to Raphael’s illustration (left) I have included my photos of Bernini’s sculpture of Aeneas fleeing Troy from the Galleria Borghese, Rome.

The Pope Leo IV, who again bears the features of Leo X, blesses the frightened crowd from a gallery located beyond the colonnades. The façade of old St Peter's appears behind him, in the background. Pope Leo IV managed miraculously to halt the raging fire, which was threatening this area of the city, by his benediction from the loggia of Old St Peter's. Thus, the Pope, through his grace, protected the people.

The Eternal Father Enthroned, surrounded by cherubim and angels sits within the golden circle of light; he holds the world, the symbol of the entire creation, in his hand; his angels have the colors of the theological virtues and are shown suspended in superhuman spirit of God.

In the Battle of Ostia (849) the troops of Leo IV met the Saracen armies in combat. Raphael’s design of the miraculous victory of the papal army is celebrated, and, in addition, he alludes to Leo X’s plans for a crusade against the Turks directed against Constantinople. Leo X, in order to stop the advance of the Ottoman sultan, Selim I, who was threatening eastern Europe, made elaborate plans with France, England, Spain, and Portugal for a crusade. His plans fell through due to England’s insistence for control. In 1519 Hungary concluded a three years' truce with Selim I, but the succeeding sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent renewed the war in June 1521 and in August captured the citadel of Belgrade. The pope was greatly alarmed, and although he was then involved in war with France, he sent about 30,000 ducats to support the Hungarians.

The naval Battle of Ostia took place in 849 in the Tyrrhenian Sea between a Muslim fleet and an Italian league of Papal, Neapolitan, Amalfitan, and Gaetan ships. The battle ended in favor of the Italian league, as they defeated the Muslims. It is one of the few events to occur in southern Italy during the ninth century that is still commemorated today, largely through the walls named after Leo IV and for the existence of this paining in the Room of the Fire in the Bargo.

News of a massing of Muslim ships off Sardinia reached Rome early in 849. A Christian armada, commanded by Caesar, son of Sergius I of Naples, was assembled off recently refortified Ostia, and Pope Leo IV came out to bless it and offer a mass to the troops, as shown here. After the Muslim ships appeared, battle was joined with the Neapolitan galleys in the lead. Midway through the engagement, a storm divided the Muslims and the Christian ships managed to return to port. The Muslims, however, were scattered far and wide, with many ships lost and others sent ashore. When the storm died down, the remnants of the Muslim fleet were easily picked off, with many prisoners taken.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Ostia, much flotsam and jetsam washed ashore and was pillaged by the locals, per jus naufragii (a medieval custom which allowed the inhabitants or lord of a territory to seize all that washed ashore from the wreck of a ship along its coast. This applied, originally, to all the cargo of the ship and the wreckage itself.) The prisoners taken in battle were forced to work in chain gangs building the Leonine Wall which was to encompass the Vatican Hill. Rome would never again be approached by a Muslim army.