Many of the artworks presented in the Palazzo Barberini from the 13th to 18th century, images of Christ’s crucifixion and the suffering of various martyrs, regardless of their religious purposes, are reminders of man’s inhumanity to man. Secularly, they are stories of the suffering that humans have imposed upon each other because of difference, and hopefully beckon us to choose a different path. Viewed from this latter perspective I believe them as visual messages from the past that have been saved to inform the present and guide us into our future.

Museum poster: Palazzo Barberini is a Baroque palace designed by three of the most important architects of the 1600s: Carlo Maderno, Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini. The entrance hall ceiling is frescoed by Pietro da Cortona (1632-1639). Palazzo Barberini became a National Museum in 1953 as a second venue of the National Gallery of Antique Art, along with Palazzo Corsini, where the Gallery had first opened in 1895. The Barberini collections provide a comprehensive insight in Italian and European culture from 1200 to 1700, with masterpieces by Filippo Lippi, Raffaello, Caravaggio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pompeo Batoni.

In 1949 the Italian State acquired Palazzo Barberini from the heirs of the Barberini family along with part of their collection, making it one of two locations for the 5,000 works of art, including sculpture, sketches, and decorative art from the 13th to the 18th century of the Nazionale di Arte Antica, along with the Palazzo Corsini, with works from the Corsini collection and adding from the Torlonia, Chigi, Mattei and Sciarra collections.

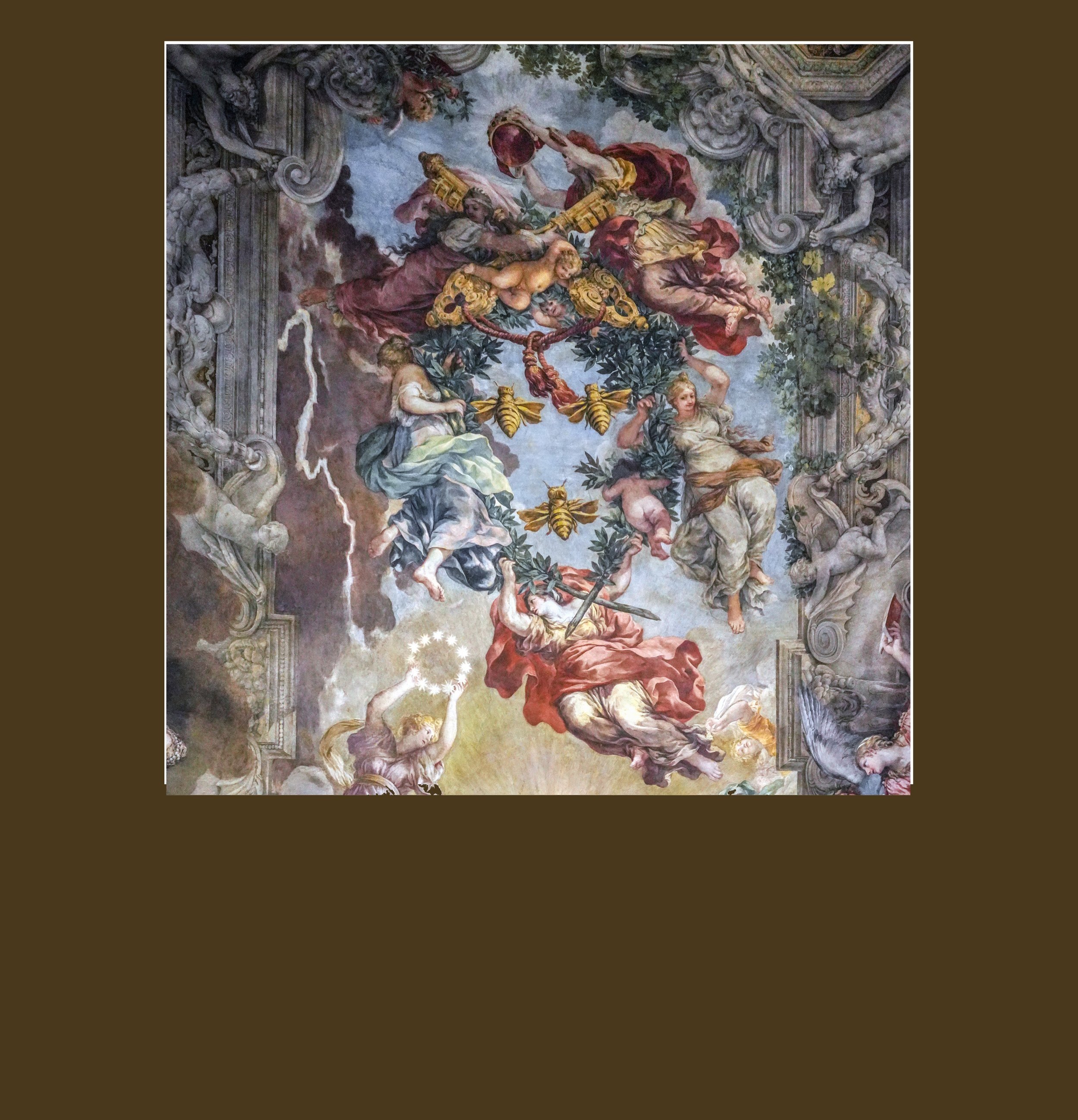

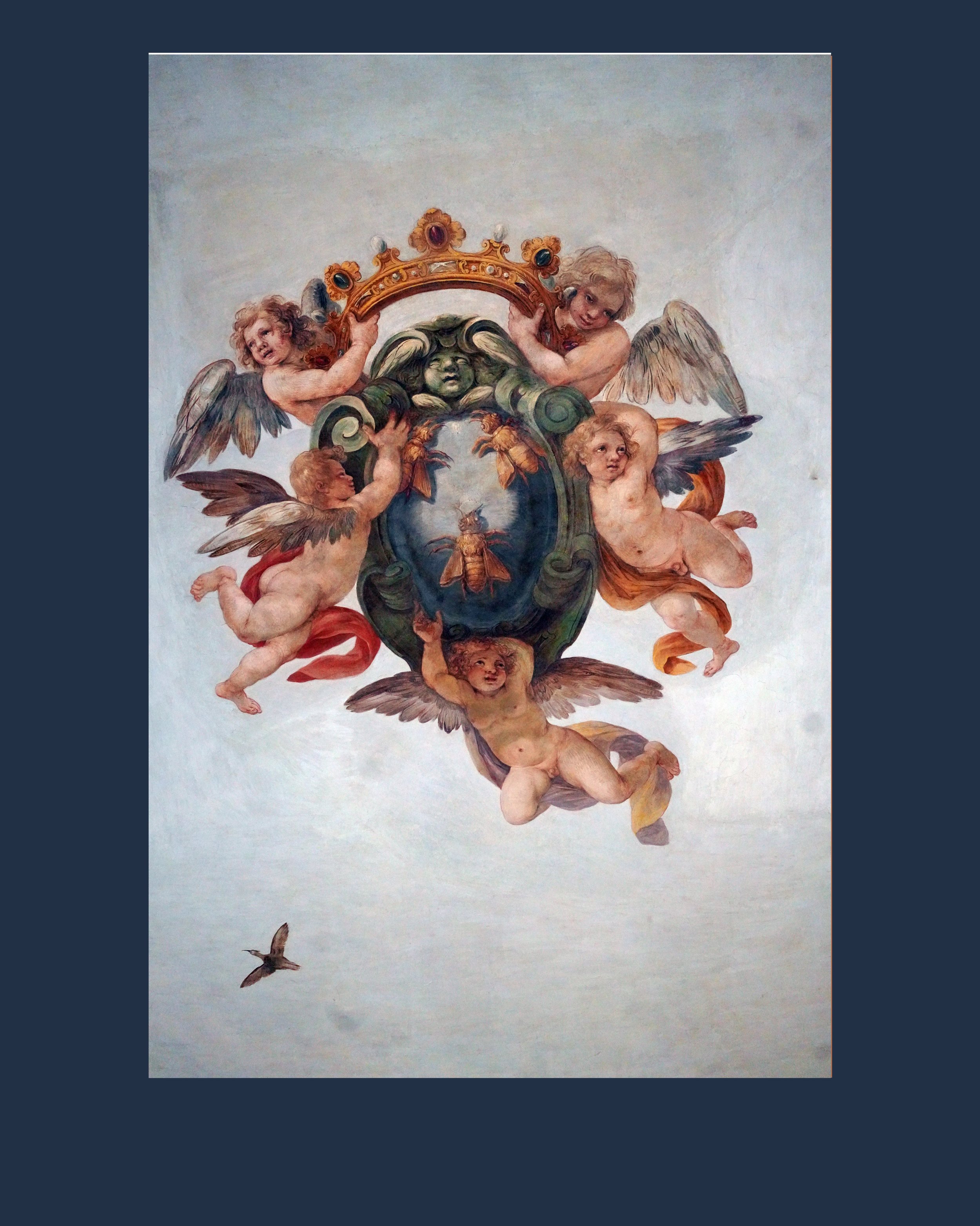

Museum label: The immense composition celebrates the spiritual and political power of the Barberini family through myriad characters – over 100 of them – set in an open space, dilated to infinity beyond the limits imposed by the architecture. The only measure which can anchor the eye is the great rectangular cornice painted illusionistically to resemble marble, dividing the vault into 5 compartments. Divine Providence is seated at the center, enthroned on clouds, holding the royal scepter and commanding Fame to crown the coat of arms of the Barberini family. In each of the side panels, opposing principles are depicted, such as vices and virtues, good and evil: Minerva fells the Giants; Theology and Religion ward off lechery and debauchery; Hercules drives off the avid Harpies; and Good Government banishes war and ensures peace. With it whirling vitality… and frenetic rhythm, the fresco is one of the earliest and most accomplished examples of Baroque painting.

In Pietro da Cortona’s Baroque ceiling, the open center of the vault celebrates the inauguration of the election of Urban VIII as pope, in which the crucial interchange between the earthly and heavenly realms occurs.

Pietro’s highly animated ‘spectacle’ of the Allegory of the Barberini Family takes place against an open sky where the figures are projected in perspective against an infinite space. In this upper section, the three theological virtues are portrayed holding up a laurel-leaf crown (symbol of poetry) which encircles three gigantic bees, an emblem of the House of Barberini and a symbol of Knowledge. Above them Religion holds up the gold keys signifying papal authority while the figure of Rome holds a tiara crown over Urban VIII to highlight the pope’s temporal and spiritual power. In this moving group, the figure of Charity marks the center of the large rectangular frame. The scene is lit by the light emanating from the image of Divine Providence below.

Divine Providence is seated at the center, enthroned on clouds, holding the royal scepter and commanding the embodiment of Rome to crown the coat of arms of the Barberini family; her head radiates light, at the apex of a pyramidal arrangement. Providence is held up by Father Time (carrying a scythe) and Fate (carrying a spindle). To the left of Providence a winged Immortality proffers a crown of stars as she flies towards the Barberini family symbol. Also, included are figures like Truth (dressed in white, below and right of Immortality) and Eternity who represent the triumph of religion and the papacy.

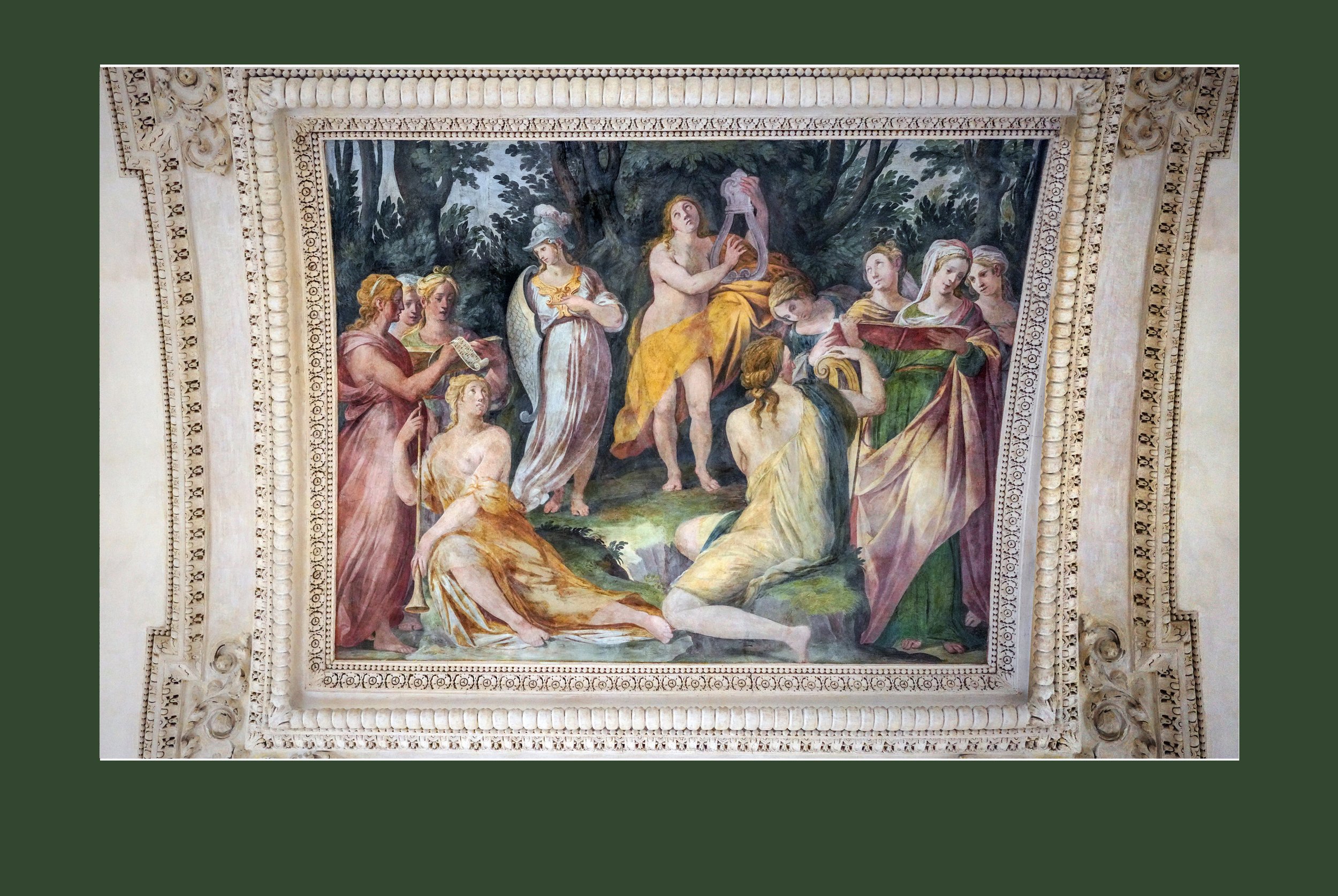

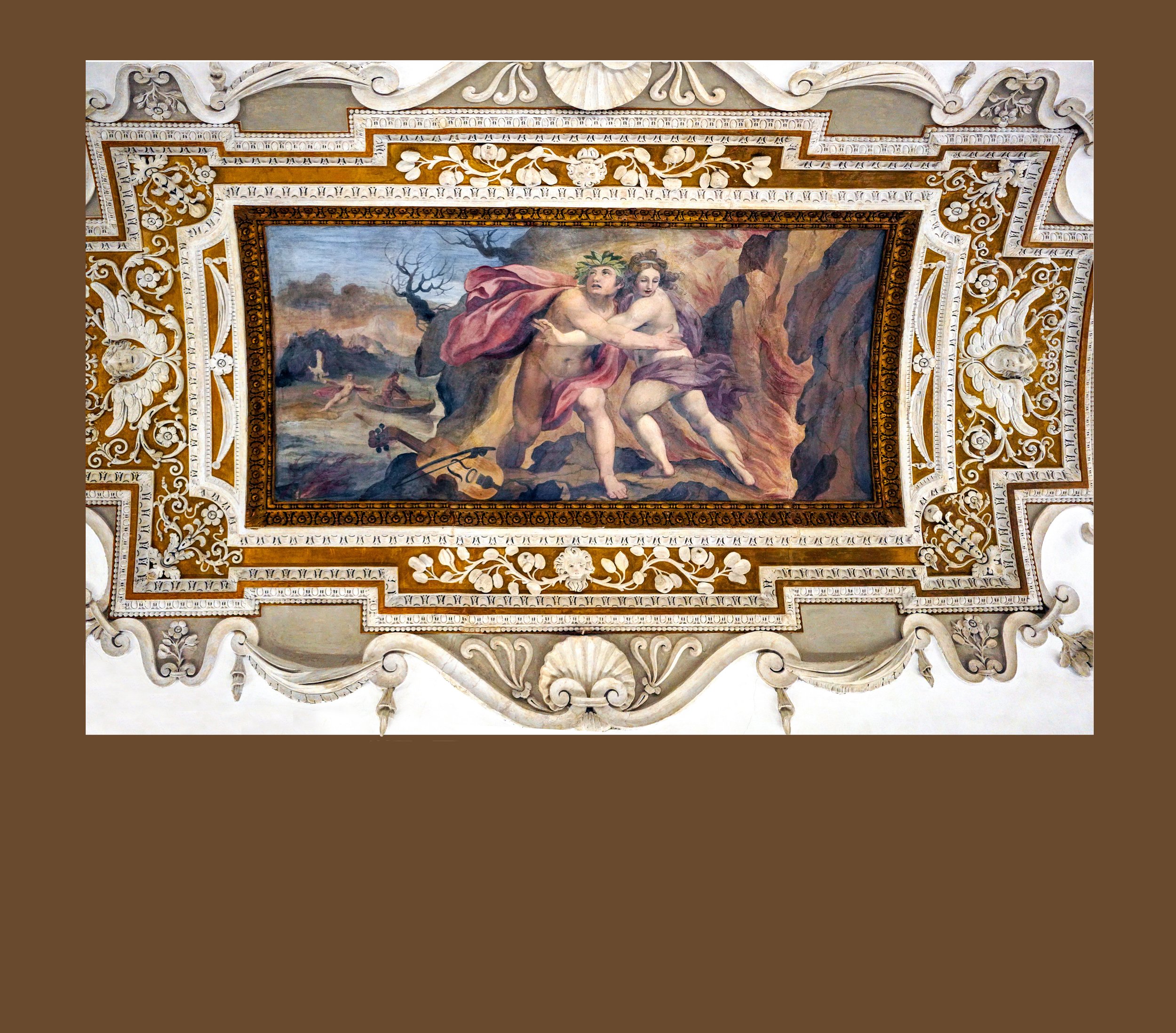

On the sides of the Allegory of Divine Providence are episodes of pagan mythology representing opposing principles, such as vices and virtues (clockwise): Hercules Drives Off the Avid Harpies, While Justice and Plenty Come to the Aid of the Beggars; Theology and Religion Ward off Lechery and Debauchery; Minerva Fells the Giants; and Good Government Banishes War and Ensures Peace. The scenes alluded to the virtue and power of the Barberini family that gave prosperity and peace to the people thanks to the primacy of intelligence over force.

The scenes in Pietro’s ceiling alluded to the virtue and power of the Barberini family who gave prosperity and peace to the people thanks to the primacy of intelligence over force. Here, he presents Hercules Drives Off the Avid Harpies, while Justice and Plenty come to the Aid of the Beggars. Hercules drives off the harpies, half-human and half-bird creatures, whose name means 'snatchers' or 'swift robbers', and who were said to steal food from their victims while they were eating. Justice carries the fasces, the bundle of rods, which in ancient Rome symbolized a Roman king’s power to punish his subjects, and later, a magistrate’s power and jurisdiction, while Plenty brings food to the poor.

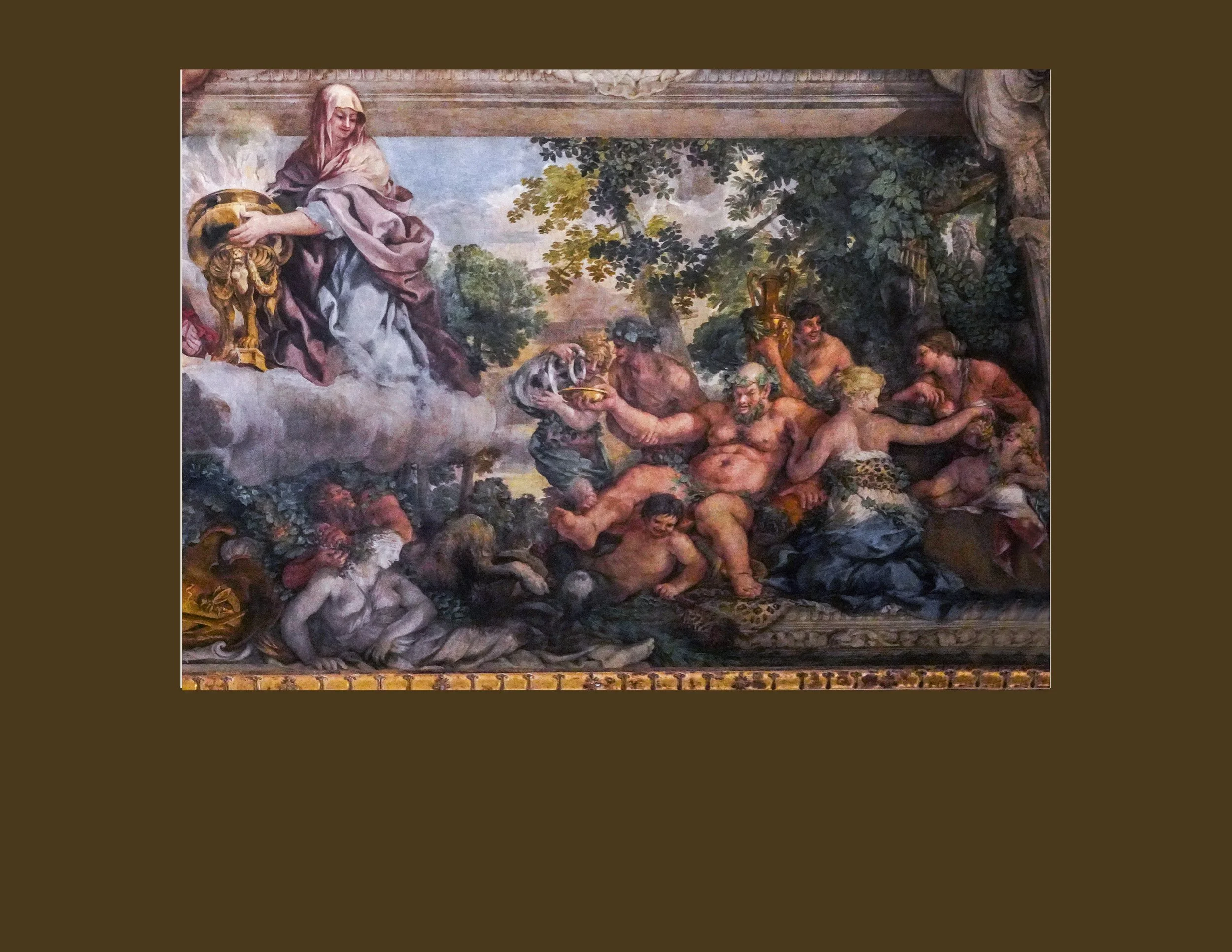

Theology and Religion ward off lechery and debauchery, in the form of Venus reclining on the left, and Silenus on the right.

Venus is in the pose described as the Venus Pudica, or "modest Venus," which referrs to the ancient Greek type of female nude, that is, a purposeful rendering of Venus so that her lower body is concealed from view. The proliferation of Venus pudica during the Renaissance marked a considerable effort to censor the female body, and its association with sexuality and eroticism.

Some traditions portray Silenus as a notorious consumer of wine, who was usually drunk and had to be supported by satyrs or carried by a donkey. He was described as the oldest, wisest and most drunken of the followers of Dionysus. Silenus may have become a Latin term of abuse around 211 BC, when it is used in the Roman playwright Titus Maccius Plautus’ Rudens (The Fisherman’s Rope) to describe Labrax, a treacherous pimp or leno, as "...a pot-bellied old Silenus, bald head, beefy, bushy eyebrows, scowling, twister, god-forsaken criminal"

Minerva Goddess of Wisdom is depicted overthrowing the giants who are seen being hurled down past the mountains they had amassed together to challenge the prominence of Heaven which is an allegorical representation of the defense of religious things.

All Pietro da Cortona’s scenes are meant to allude to the virtue and power of the Barberini family who purportedly gave prosperity and peace to the people thanks to the primacy of intelligence over force. Here Good Government rules over Vulcan's Forge on the left and Furor, on the right, who is bound as Peace closes the Janus temple.

The allegory purports war can be stopped by Good Government. War is symbolized by Vulcan who is forging armaments, many of which are strewn on the ground in front of the forge. Vulcan made thrones for the other gods to sit on in Mount Etna, a volcano on the east coast of Sicily. Through his identification with the Hephaestus of Greek mythology, Vulcan came to be considered as the manufacturer of art, arms, iron, jewelry and armor for various gods and heroes, including the thunderbolts of Jupiter.

Pietro’s Good Government bounds Furor (bottom right), which according to Virgil’s Aeneid (1.148-56) influences the crowd, causing their anger to boil over into violence. Conversely, the wise statesman is a leader of great virtue who uses this to calm their anger and return them to their senses. The result is Peace (upper middle), who Pietro depicts closing the doors of the Janus Temple. Plutarch, in Life of King Numa, wrote that the Janus Temple at Rome had double doors, which they call the gates of war; for it always stands open in time of war, but is closed when peace has come. The latter was a difficult matter, and it rarely happened, since the realm was always engaged in some war, as its increasing size brought it into collision with the barbarous nations which encompassed it round about.

Palazzo Barberini presents a chronological and representative configuration of the leading schools of painting from the 13th to the 18th century. The 16th and 17th centuries are the most represented centuries with works by Raffaello, Piero di Cosimo, Bronzino, Hans Holbein, Lorenzo Lotto, Tintoretto, up to Caravaggio and his "Caravaggeschi" followers and the prosperous 17th century with works by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Guido Reni, Guercino, Nicolas Poussin, Pietro da Cortona. Below, we begin with works from the 11th century collection.

The canonical Byzantine figure known as Haghiosoritissa, The Madonna of Intercession/Advocate, in which Mary is depicted without the Christ Child, with both hands raised, is joined here by the uncommon detail of an image of Christ blessing. He appears to grant the prayers of the Madonna Advocata and possibly also to seal the authenticity of this icon thought to be miraculous.

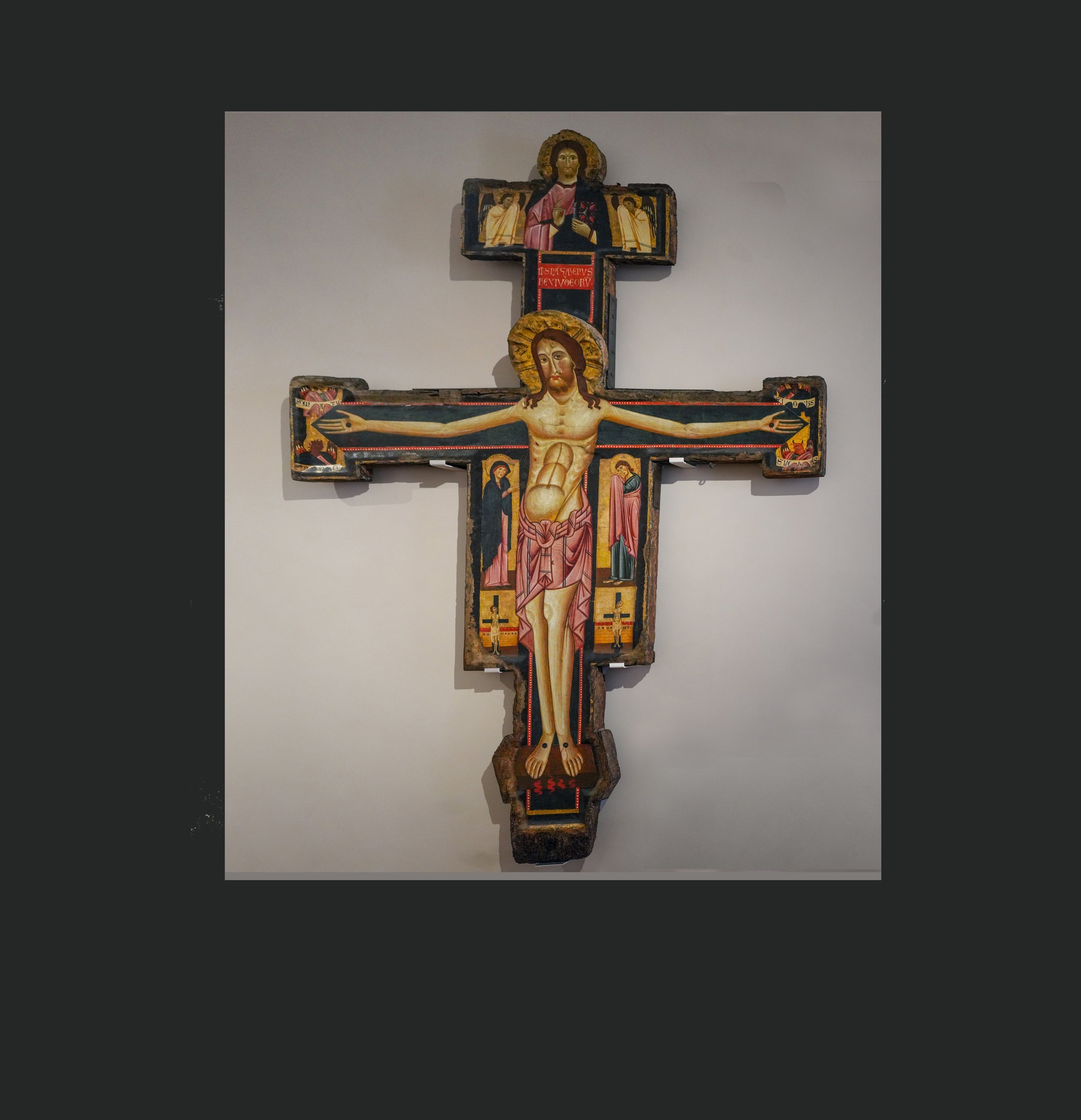

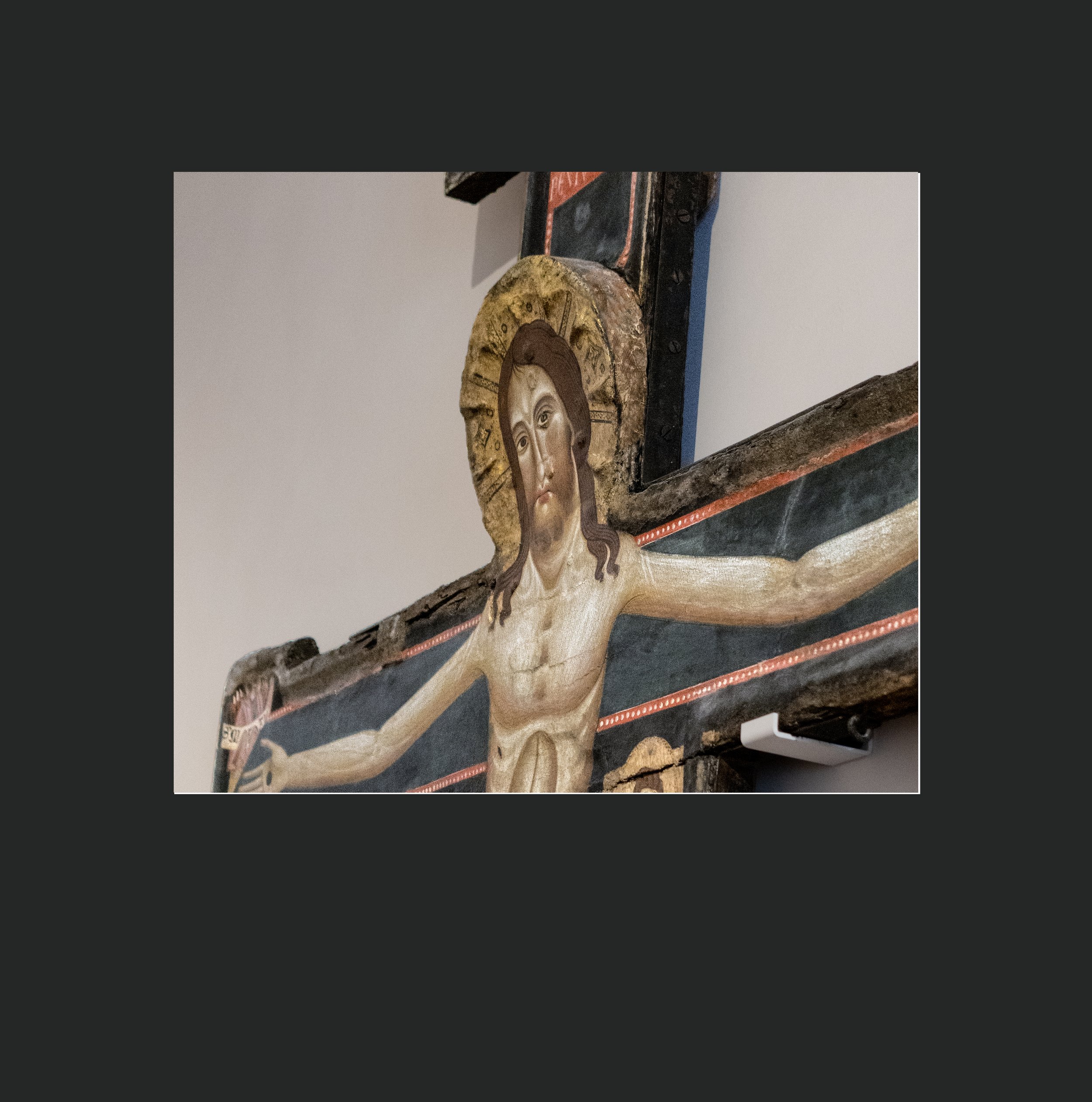

From the museum label: “In the culminating act of the crucifixion, Jesus shows us the fatal wound in his rib cage, yet in accordance with an ancient tradition he is alert and virtually insensitive to his suffering. Thus the image clearly seeks to convey Christ’s dual nature: his human nature “without comeliness and liable to suffering”, in the words of Irenaeus of Lyon (130-202, Adversus haereses 3, 19:2), but more importantly, the triumphant “impassive” nature of the Deus fortis (God is strong).

Berlinghieri’s Crucifix is intended to bring into the reality of the ritual the iconic presence of the crucified Christ, alive (Christus triumphans – Christ triumphant), as a powerful deity who could overcome the torment of the Crucifixion. That is one of the reasons why Christus Vigilans (Christ the Watcher), being alive, appeals to the worshipper to look him in the eye, mindful of Psalm 121(4): "Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep". Christ's face is often painted, as here, on a tilted wooden support projecting out from the panel precisely so that he can look directly at the worshipper.

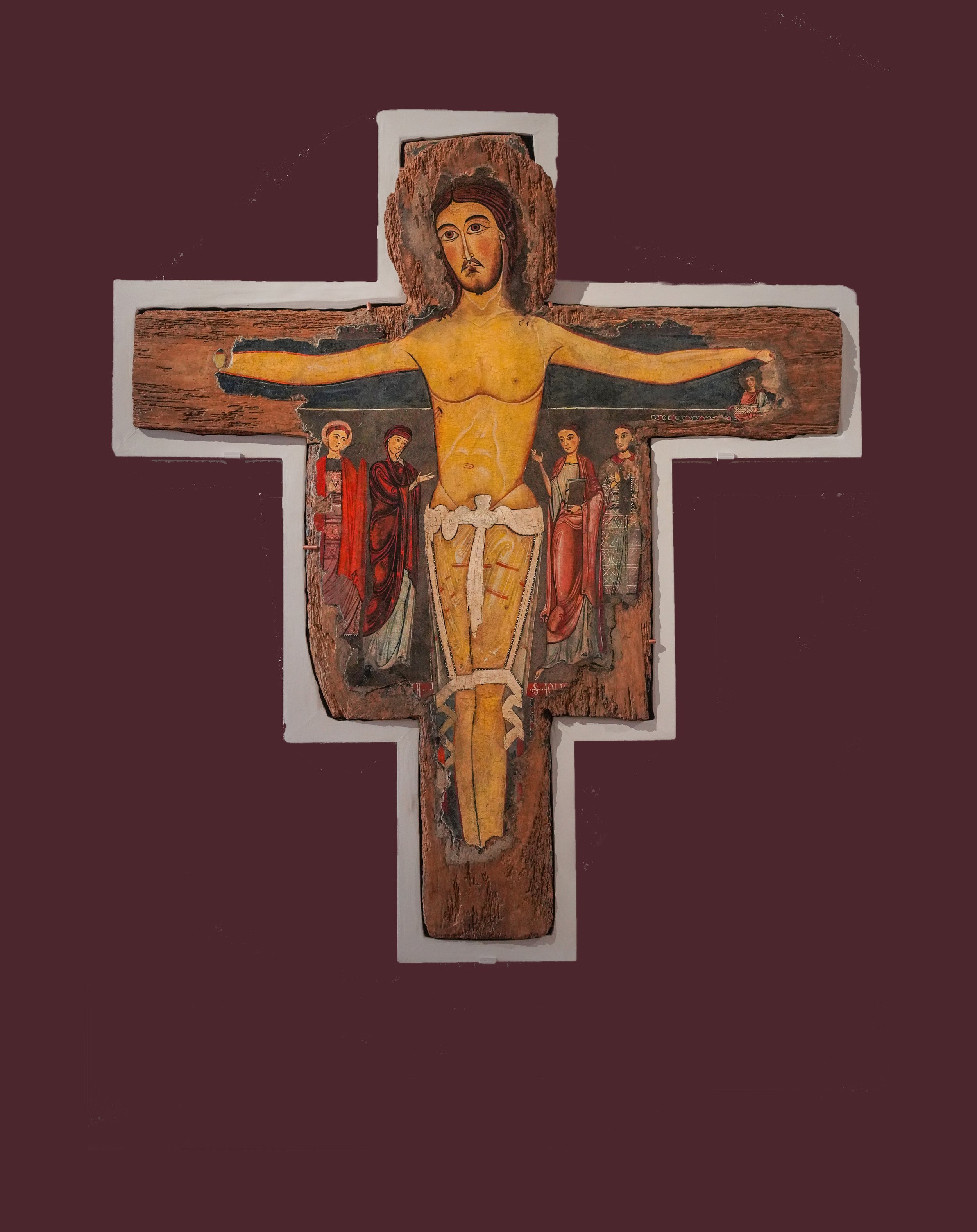

Based on the museum label: This cross by the so-called Florentine master “of Bigallo” perfectly illustrates such images can represent a composite of ideas, merging historical events with their past, present and future symbolic meanings. For example, at the top of the cross Christ reappears, blessing, above Mary interceding who also appears beside St. John on Golgotha (on the sides of Christ’s torso).

From the museum label: The panel at the foot of Bigallo’s cross shows the (historical) Gospel story of St. Peter's denial, with the rooster prophesying the apostle's betrayal and sin. That is why the Redeemer's blood penetrates the bowels of the earth and bathes the skull which an early tradition tells us belonged to Adam, who was buried beneath Calvary. Thus, the cross is the linchpin between earth and heaven, between sin and salvation, between man's history and divine providence.

From the museum label: This cross is a magnificent example of an iconographical type that was developed and disseminated throughout the 12th century, particularly in central Italy. The primary function of such paintings was to conjure up the historic episode of the crucifixion in narrative form which explains the presence of the mourners, the Virgin Mary and St. John, on either side of the cross, on Golgotha.

Based on the museum label: The image of Christus Patiens (Christ Suffering), dying or even dead on the cross, had been known in Byzantium and the West since at least the 9th century. In the 13th century, “Christ suffering" acquired a more specifically pathos-filled, sentimental tone, e.g., Machilone paints Jesus's face wearing a moving expression of grief and uses side panels to give more room to Christ's body as it bends under the weight of death.

Simone and Machilone use iconography as a visual response to certain heretical positions current in the 13th century, e.g., Monophysites and Docetists, that denied the full reality of Jesus's human suffering. To emphasize the reality of Christ’s human suffering, in addition to the expression of grief on the face of Jesus, they mirrored that human emotion, as shown here at the end of Christ’s arms, in the gestures of the Virgin and St. John as they dry their tears.

The lyre of Apollo is an image of the celestial harmony, or the melody caused by the orderly revolutions of the celestial spheres. The lyre symbolizes the joy of connecting with the gods of Olympus through music, poetry, and dance. It also represents wisdom, moderation, and the peace of Elysium, the paradise where heroes go after the gods grant them immortality. Elysium is the closest Ancient Greek equivalent to the more modern, Abrahamic concept of heaven.

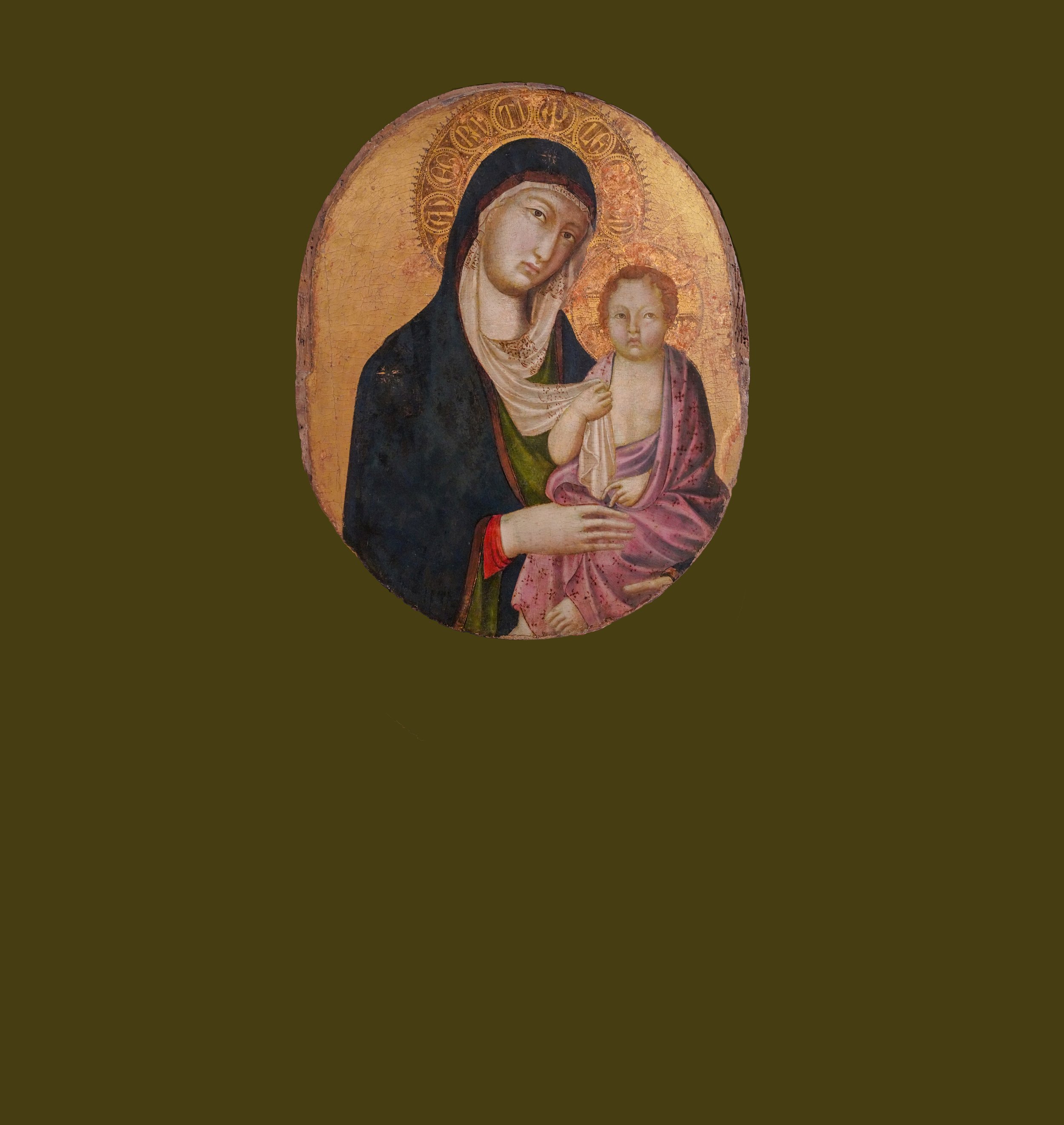

Segna di Bonaventura’s Madonna and Child is an excellent example of the persistence of the Byzantine style. It emerges here in the composition’s rather archaic hieratic and stern mood and in the drapery’s pure linear, golden or “chrysographic” treatment (i.e., the “golden highlighting” through use of gold lines in the image to define features such as the folds of clothing, as seen here in the Madonna’s scarf). The greenish hue of the figure’s flesh, is caused by the resurfacing of a primer layer created using the technique known as “verdaccio” or “bazzeo”. The image focuses on the gesture of Jesus as he grasps Mary’s veil, foreshadowing the shroud of his Passion.

Based on the museum label: Nicolo, the son of Segna di Bonaventura, whose uncle was Duccio, all painters of the Sienese school, presents Madonna and Child with an elaborate decoration of the Virgin's halo, which bears the inscription: "Ave Gratia Plena D[omi]n[us Tecum]" (Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with you). The red sleeve of Mary’s blouse – traditionally a male, powerful, nearly divine color – is almost entirely hidden by her midnight blue cloak – receptive, quiet, humble like the night. Jesus's symbolic gesture involving raising and showing the Virgin's veil symbolizes the relationship between mother and child, e.g., the human nature that Christ inherited from his mother as well as their loving bond.

From the museum label: The anonymous Palazzo Venezia Master - named for the museum in which this panel once hung – was a pupil or follower of Sienese painter Simone Martini, whose technique he emulated, particularly in the skilled application of punching (i.e., technique using mechanical tools to impress repeated motifs on gold foils to create decorative patterns) and so-called “sgraffito” (i.e., a technique that involves scratching a surface to create a pattern or shape from an underlying color) in his treatment of finely decorated damask fabrics. The figures gaze outwards in this picture while the Christ Child points to a scroll on which the words that he himself was to address to his apostles - “I am the way, the truth, and the life:” (John 14:6).

Museum label: This small triptych reveals the dual tendency that was such a feature of Late Gothic painting in Italy. On the one hand, the cloth of honor hanging behind Mary becomes an ornamental heraldic drape, while on the other, the artist breathes life into the iconic formula of the Virgin and Child, as they look into each other’s eyes, in an attempt to lend the figures and their gestures a more vibrant psychological immediacy and to offer them a more tangible and sculptural concrete space. The triptych, …is signed “Symon pincxit”.

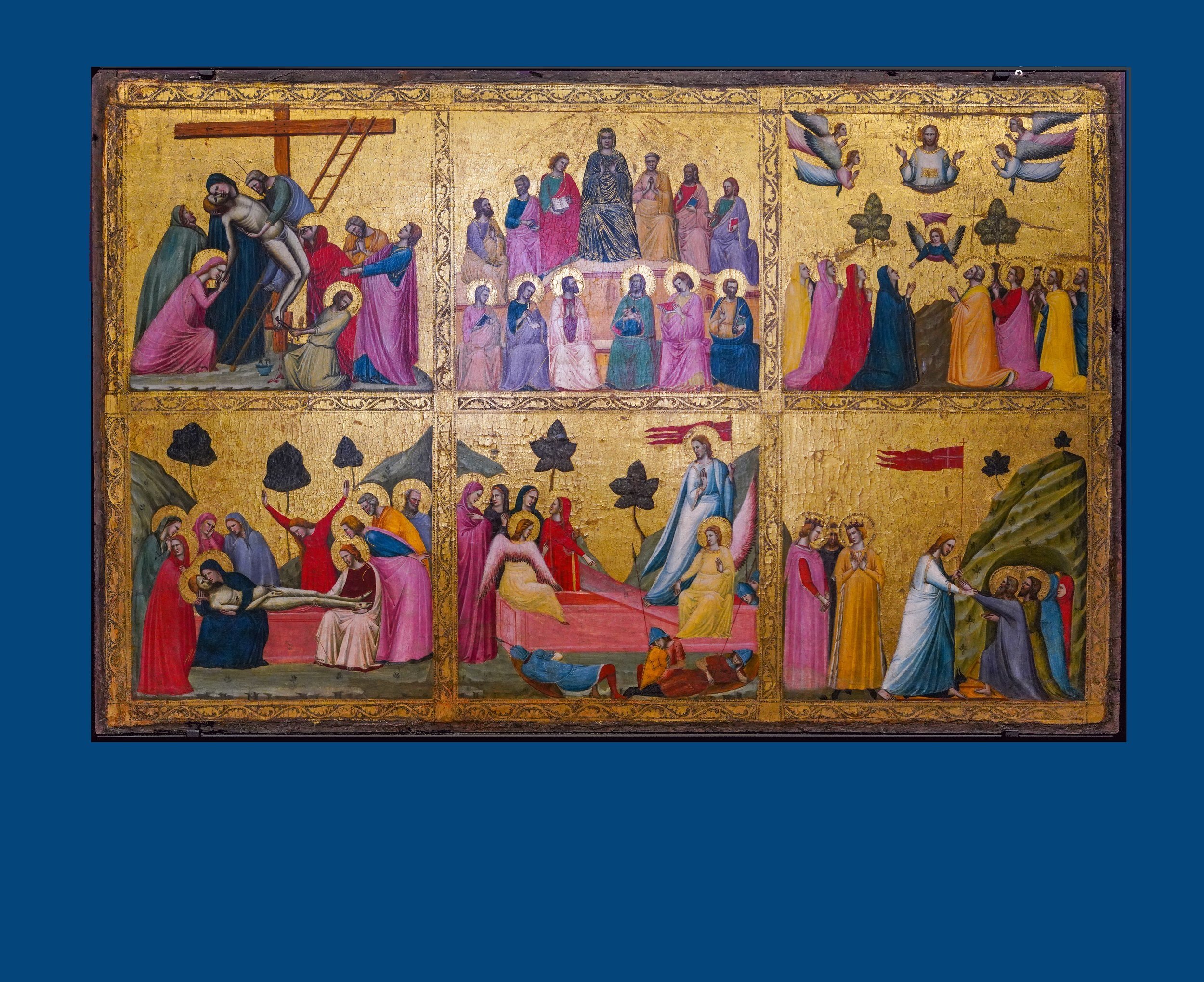

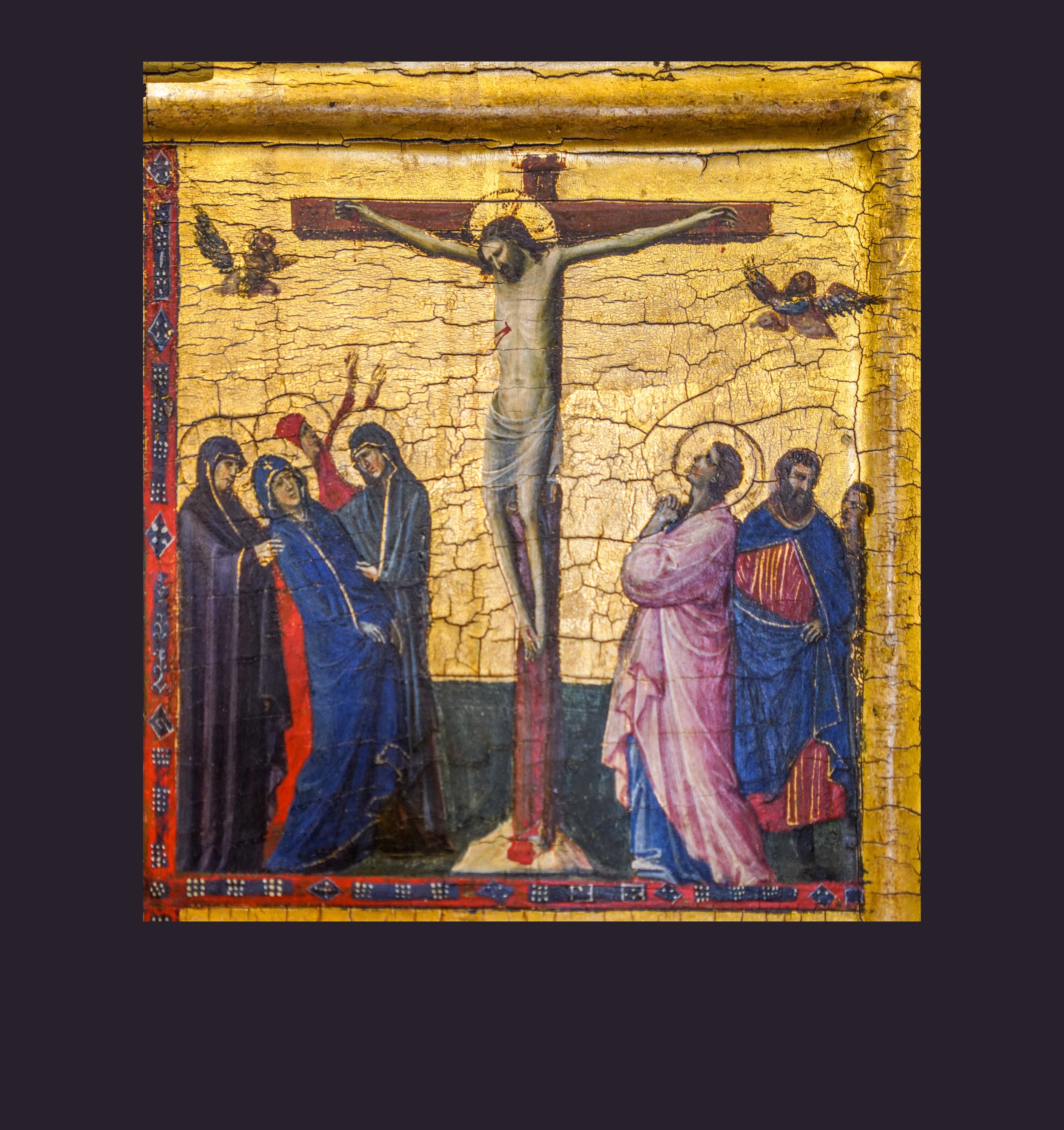

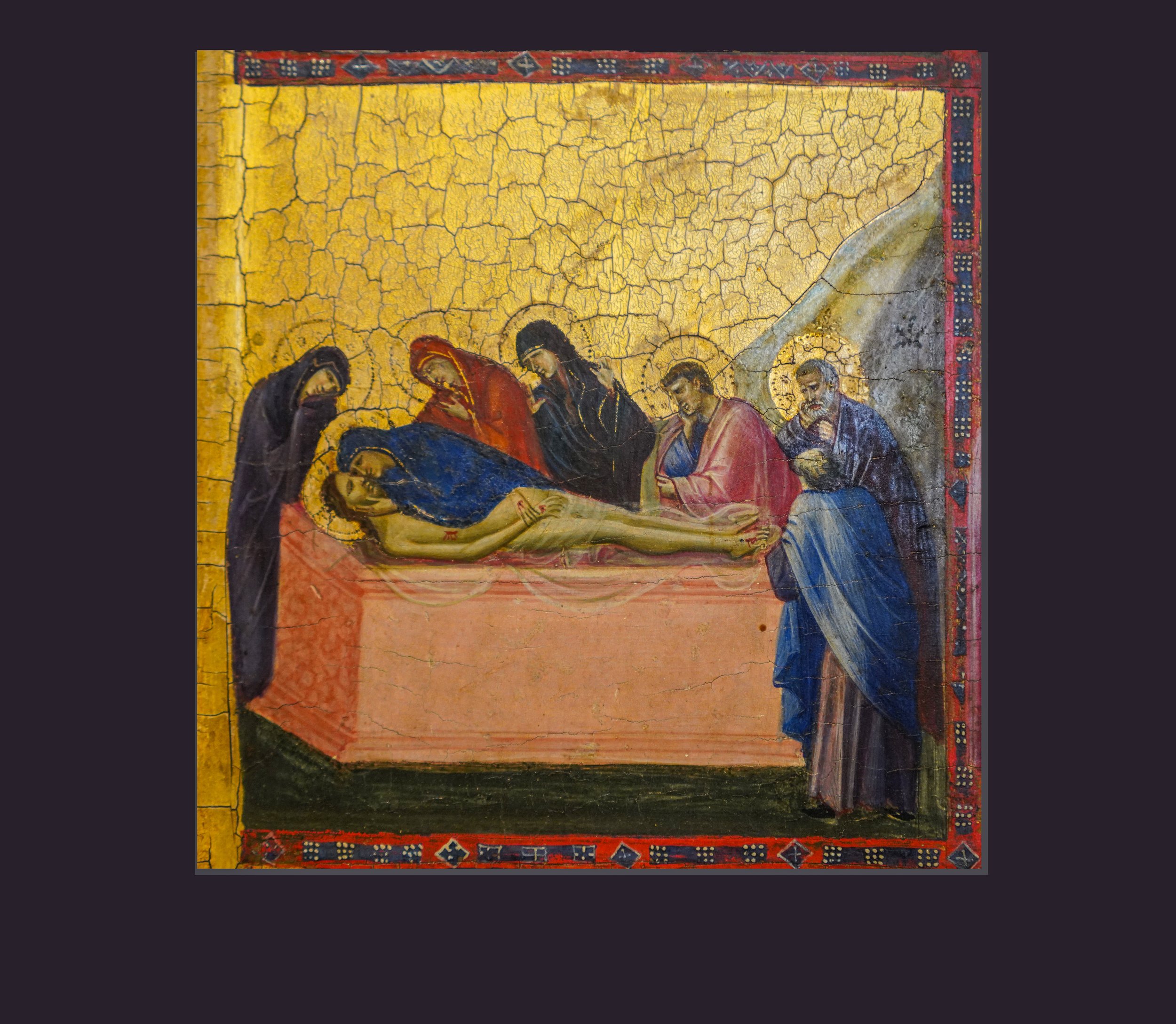

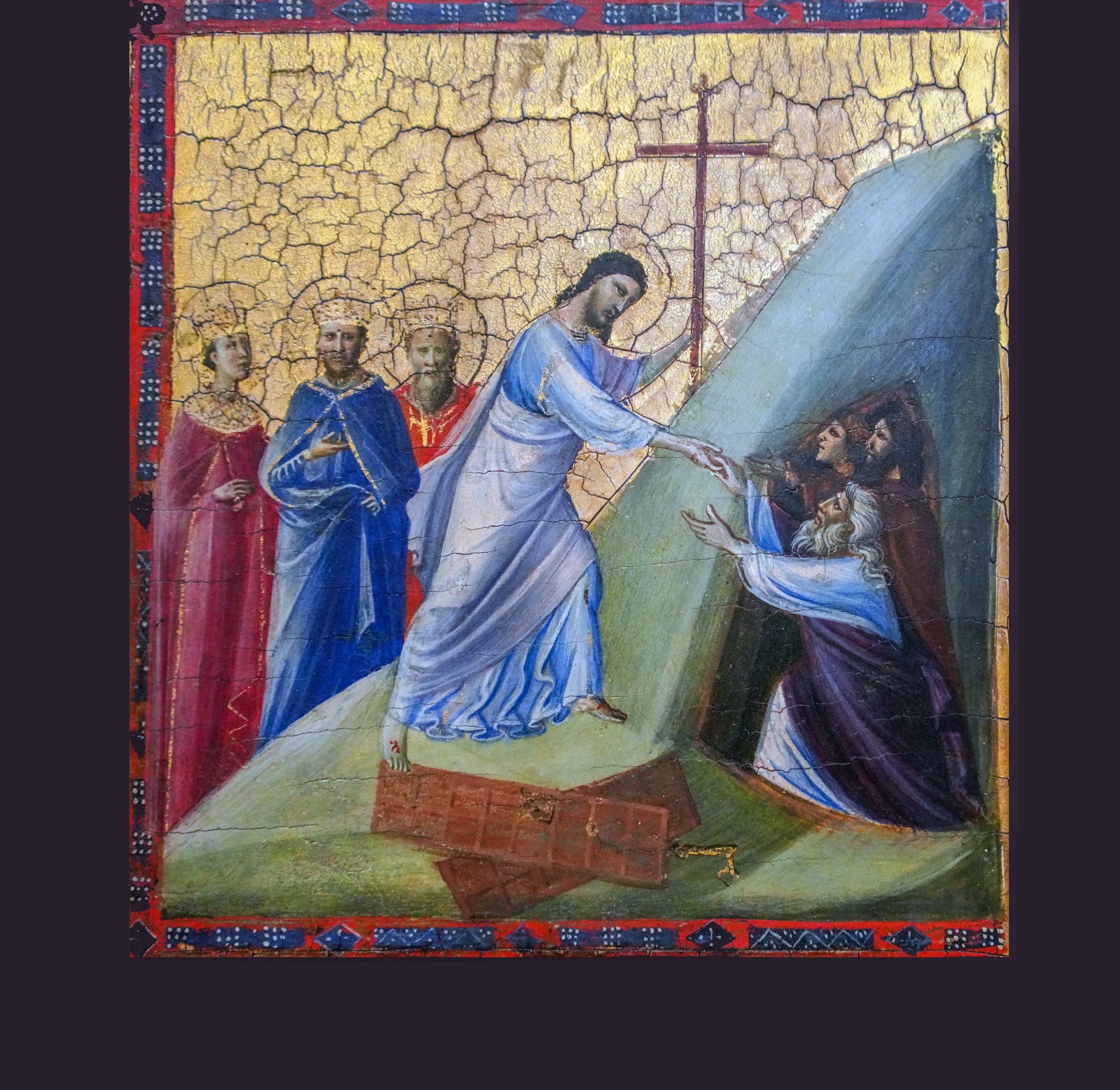

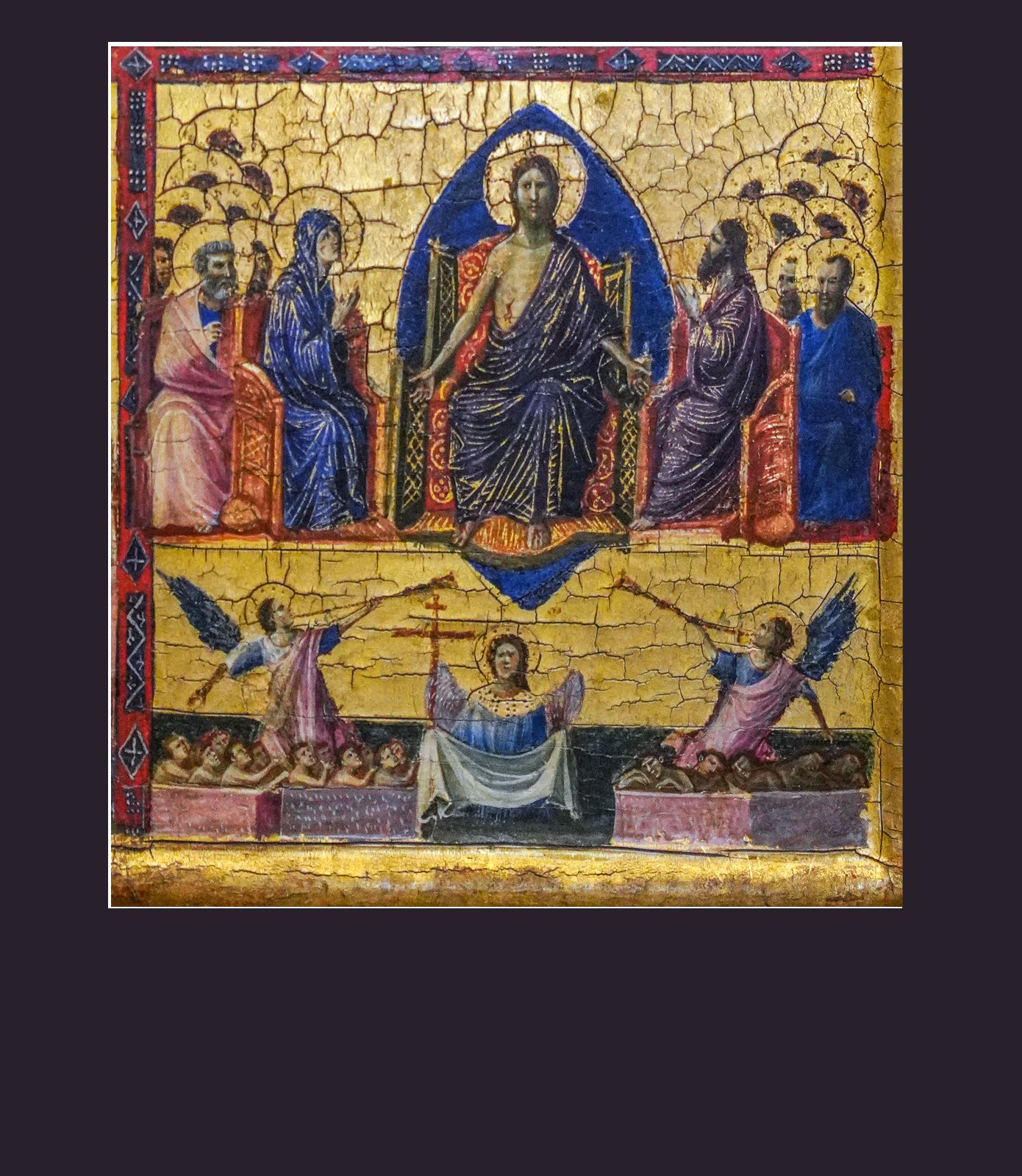

Giovanni Baronzio depicts six episodes from the Passion of Christ inserted in square compartments in a counter-clockwise order; starting from the top left the episodes are: Deposition, Lamentation, Resurrection, Descent into Limbo, Ascension, and Pentecost. Multiple aspects of this work, such as the narrative structure, the color palette and the search of naturalism in the representation of bodies and spaces, manifest the great influence of Giotto upon the Rimini school in the fourteenth century.

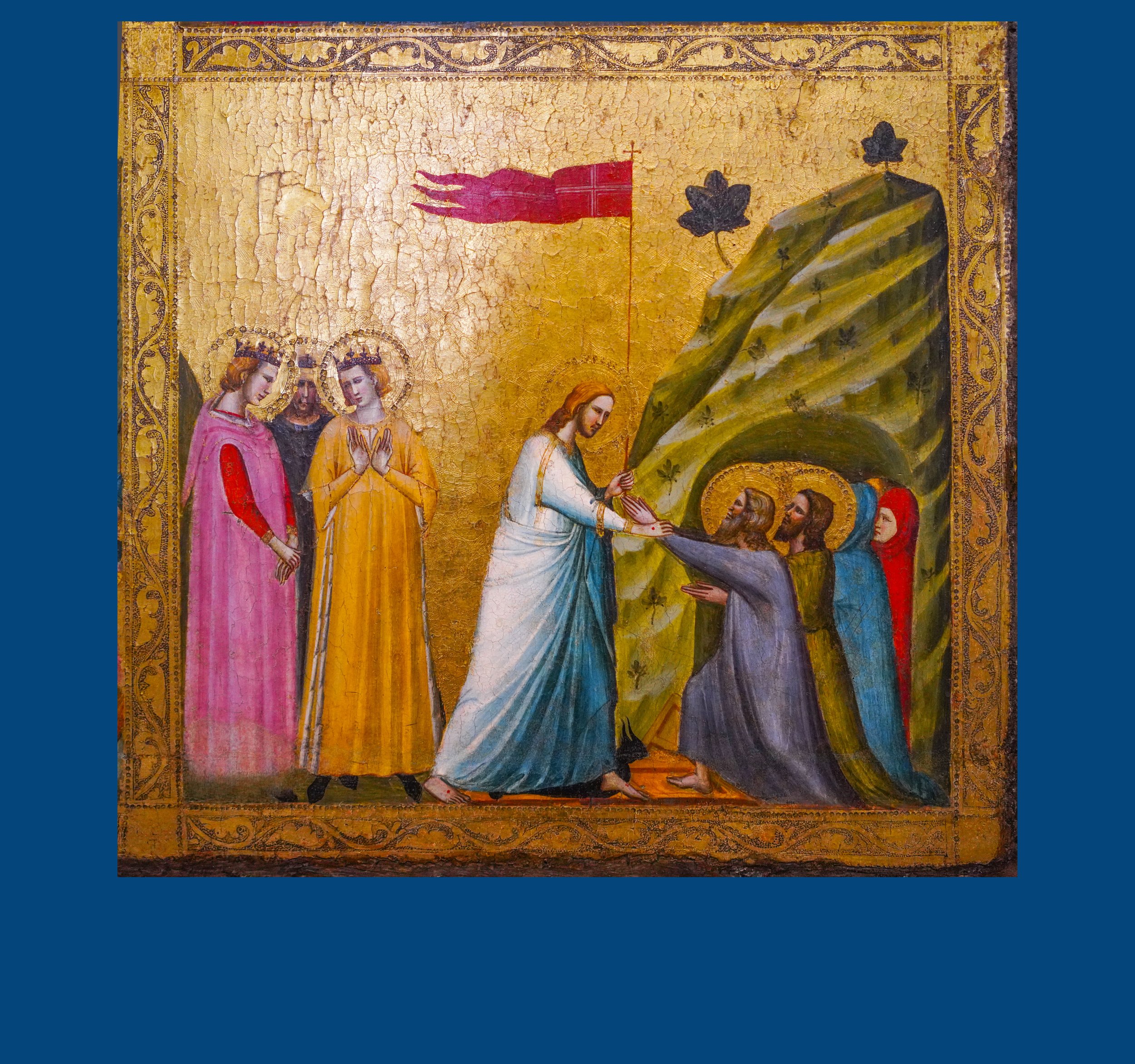

In the lower right compartment of the Stories of the Passion of Christ, Baronzio shows Christ, after his death, when he was supposed to have descended into the underworld, to free Adam and Eve, all the righteous, and the souls of Old Testament saints, and take them up to heaven. The church taught that those who died before the Christian sacraments would be relegated to a lower place until Christ could redeem them.

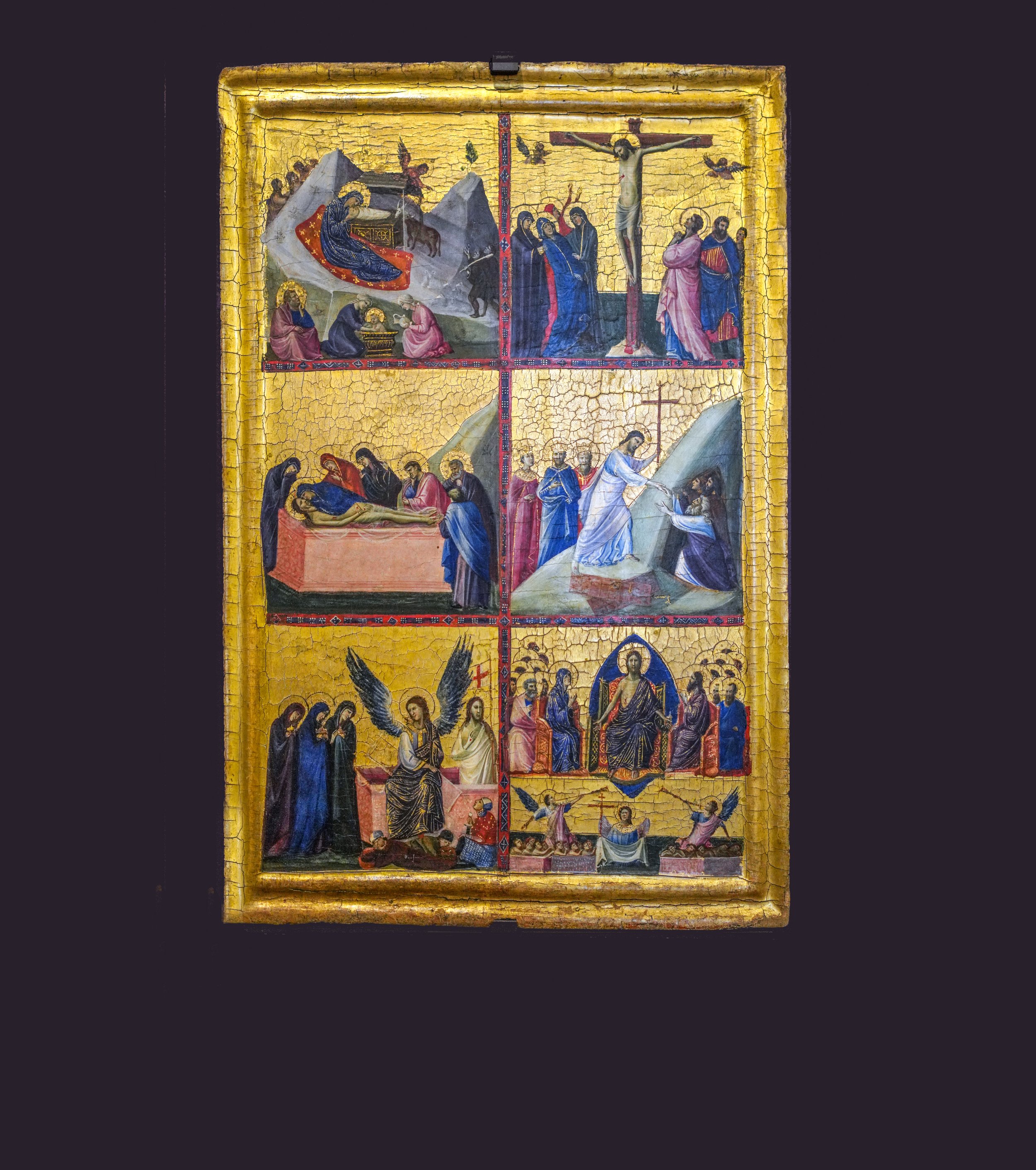

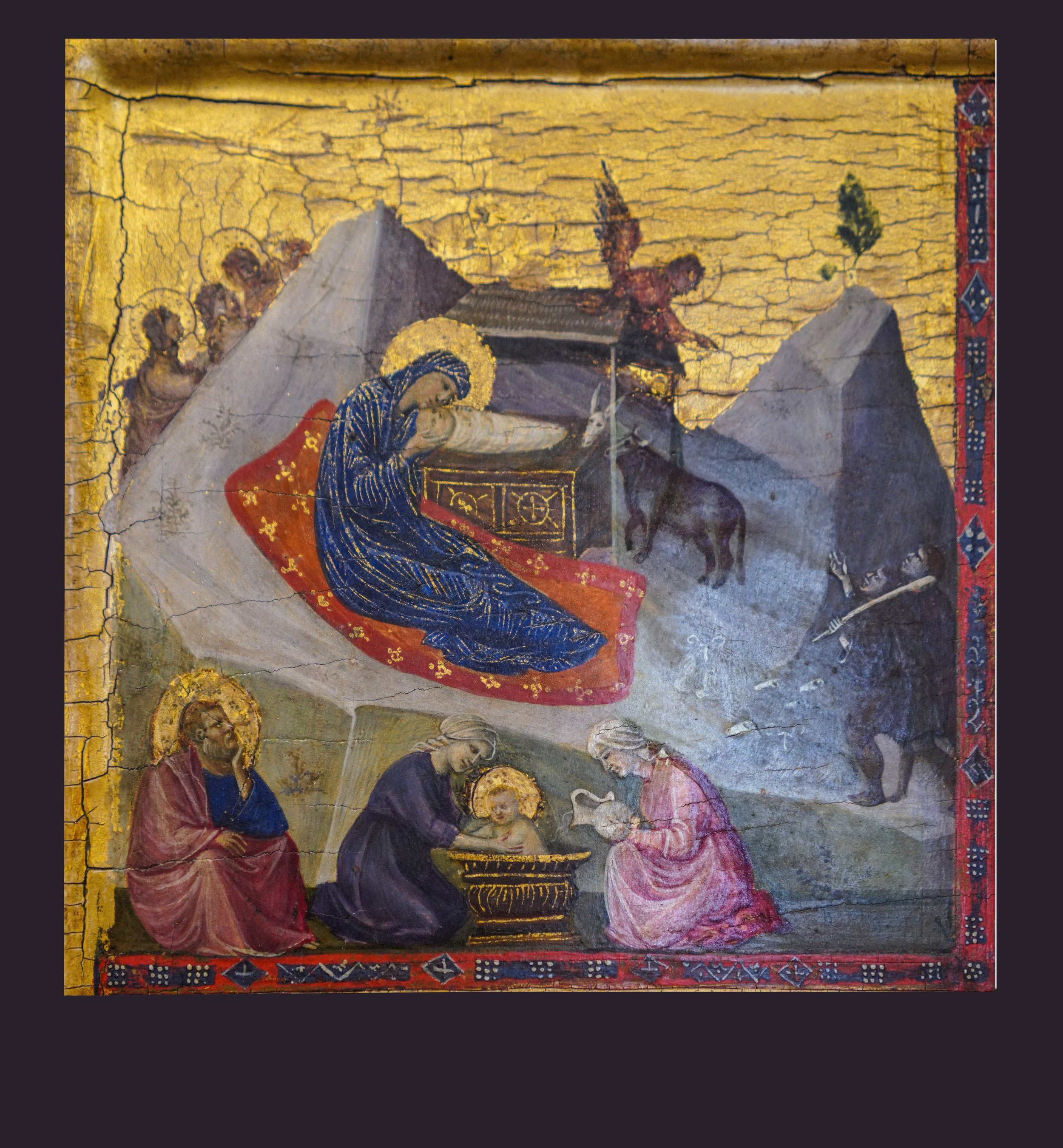

In Scenes from the Life of Christ, Giovanni Baronzio presents a complex interpretation of events, e.g, the Virgin’s tender kiss in the Nativity scene (top left) heralds the final, tragic kiss at the tomb immediately below, accentuating the bond between the “mystery” of the birth and the crucifixion by emotional contrast. Scenes right to left: Nativity, Crucifixion, Lamentation, Descent into Hell (Limbo), Resurrection, and Day of Judgment.

From museum label: In stylistic terms Baranzio (da Rimini) combines realistic and pathos-filled effects, mindful of Giotto’s teachings, with skilled sophistication on a more abstract register, resorting to the golden Byzantine style too depict such other-worldly realities as Christ’s final manifestation in The Day of Judgment (here) or the angel of the Resurrection (next photo).

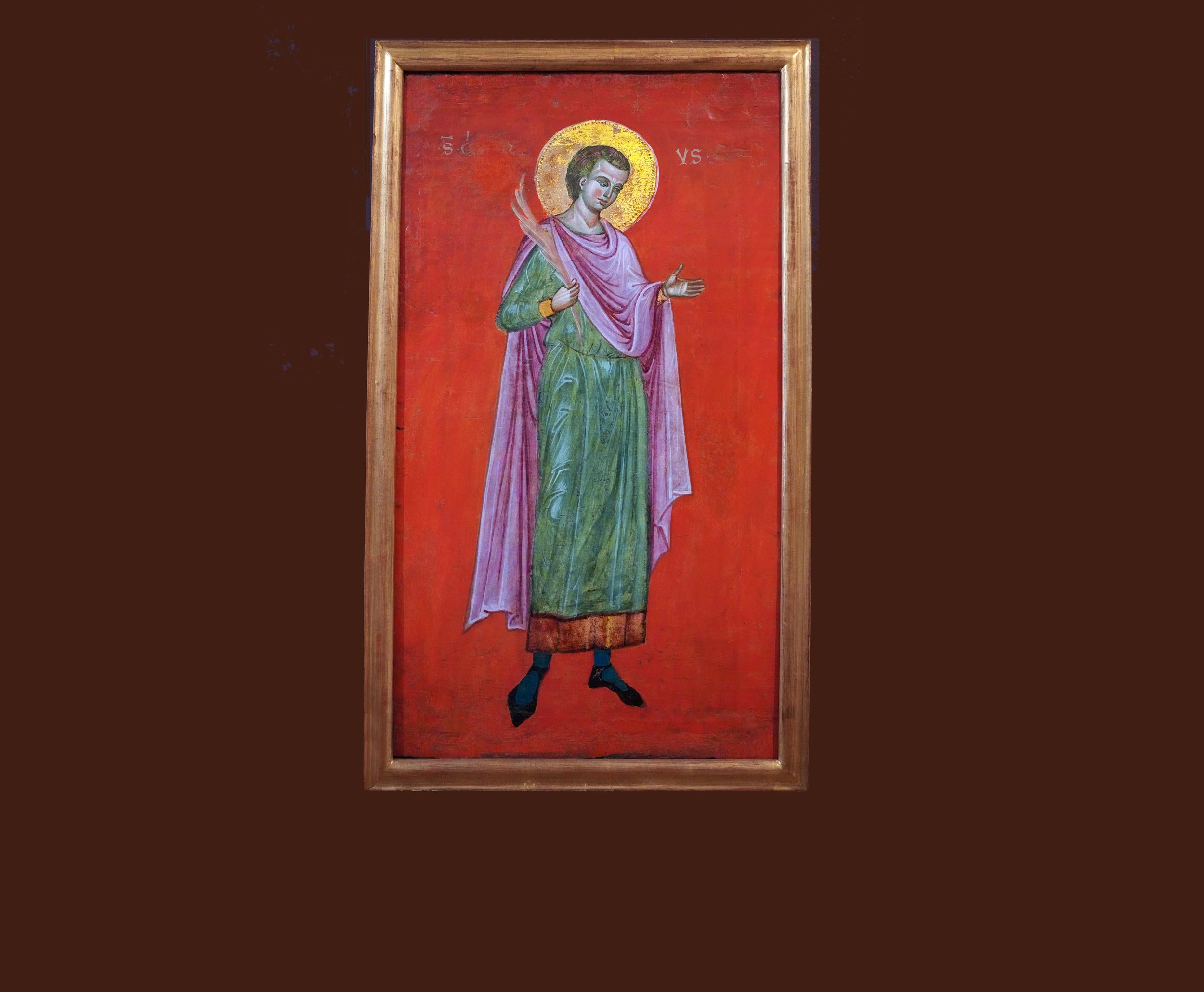

Museum label: "The showy scarlet background in both St. Cipriano (here) and St. Erasmus (below) marks the Venetian master’s close bond with the Byzantine figurative tradition that was so deeply ingrained and influential in Venice and the Adriatic area for such a long time. That a bond also emerges in his treatment of the folds in the drapery and his graphic, linear stylization of highlights, especially in the figure of the martyr Cyprian," who was beheaded on September 14, 258. Cyprian had already been imprisoned and exiled to the City of Curubis the year before for his refusal to burn incense to the Roman gods. He was brought back to Carthage to stand trial again, as the new proconsul, Galerius Maximus, was anxious to enforce the death penalty.

Museum label: “The two panels, St. Erasmus and St. Cipriano once formed part of a structure comprising several more pieces, possibly a polyptych. That they were most probably painted by a Venetian master is suggested by the showy scarlet background peculiar – not to say exclusive – to a type of production typical of 14th century Venetian painting.” Bishop Erasmus was martyred around the year 303, after Western Roman Emperor Maximian had tortured him several times only to have him heal and escape with the help of an angel. Upon Erasmus’ re-capture, Maximian had Erasmus’ abdomen cut open and his intestines wound around a windlass and slowly pulled out, thus killing him. Thus, he’s invoked against stomach/intestinal problems.

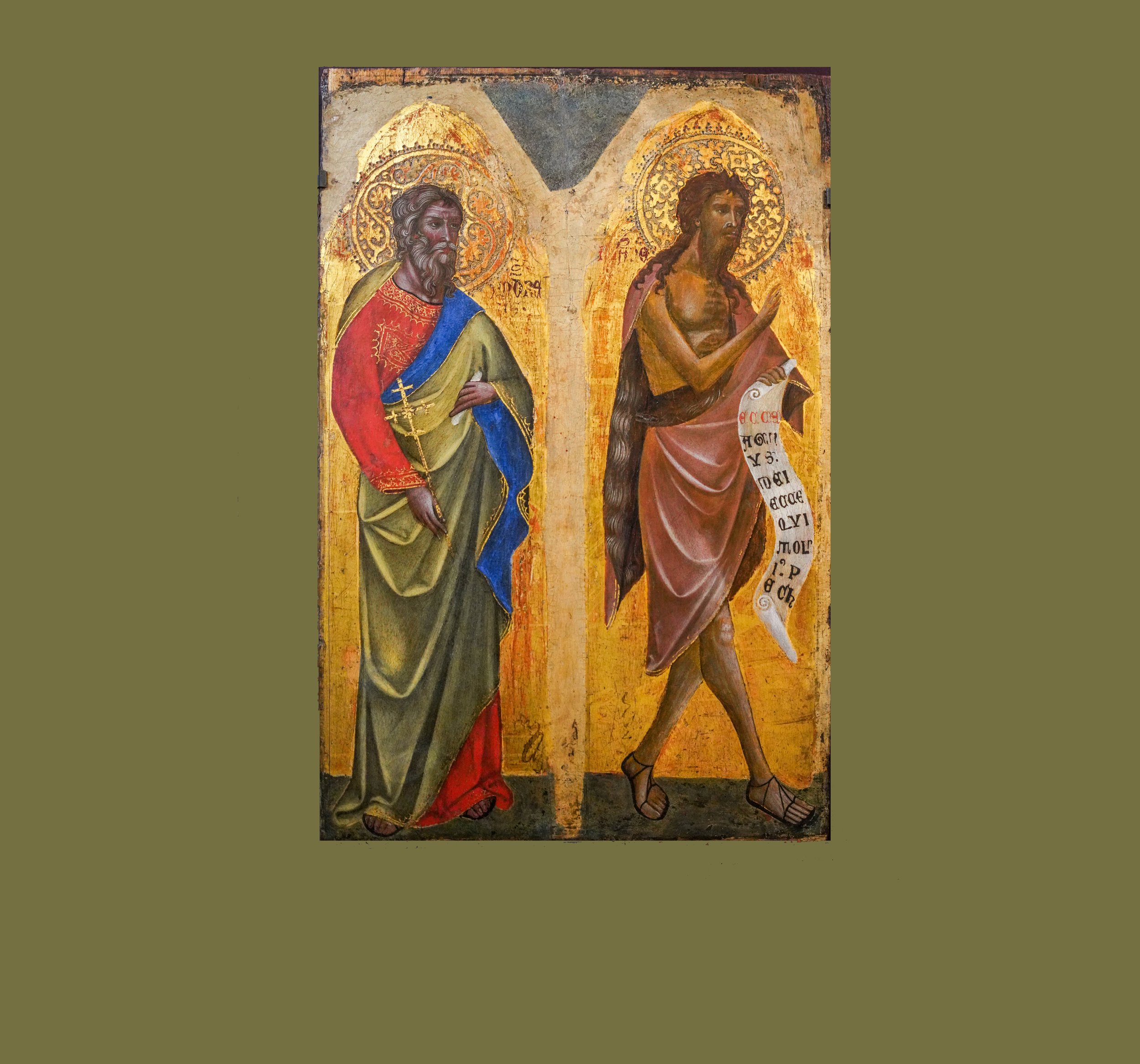

Museum label: “The two saints are conceived in a style that strikes a balance between Byzantine tradition and the search for a more vibrant palette and a more elegant line, hinting at the influence that the courtly International Gothic style was to have on Venetian painting from the mid-14th century.” Saint Andrew, a fisherman, was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus. The title First-Called stems from the Gospel of John, where Andrew, initially a disciple of John the Baptist, follows Jesus and, recognizing him as the Messiah, introduces his brother Simon Peter (St. Peter the Apostle) to him. John the Baptist is revered as a major religious figure in Christianity, Islam, the Bahai faith, the Druze faith, and Mandaeism. According to the New Testament, John was sentenced to death and subsequently beheaded by Herod Antipas around AD 30 after John rebuked him for divorcing his wife and then unlawfully wedding the wife of his brother.

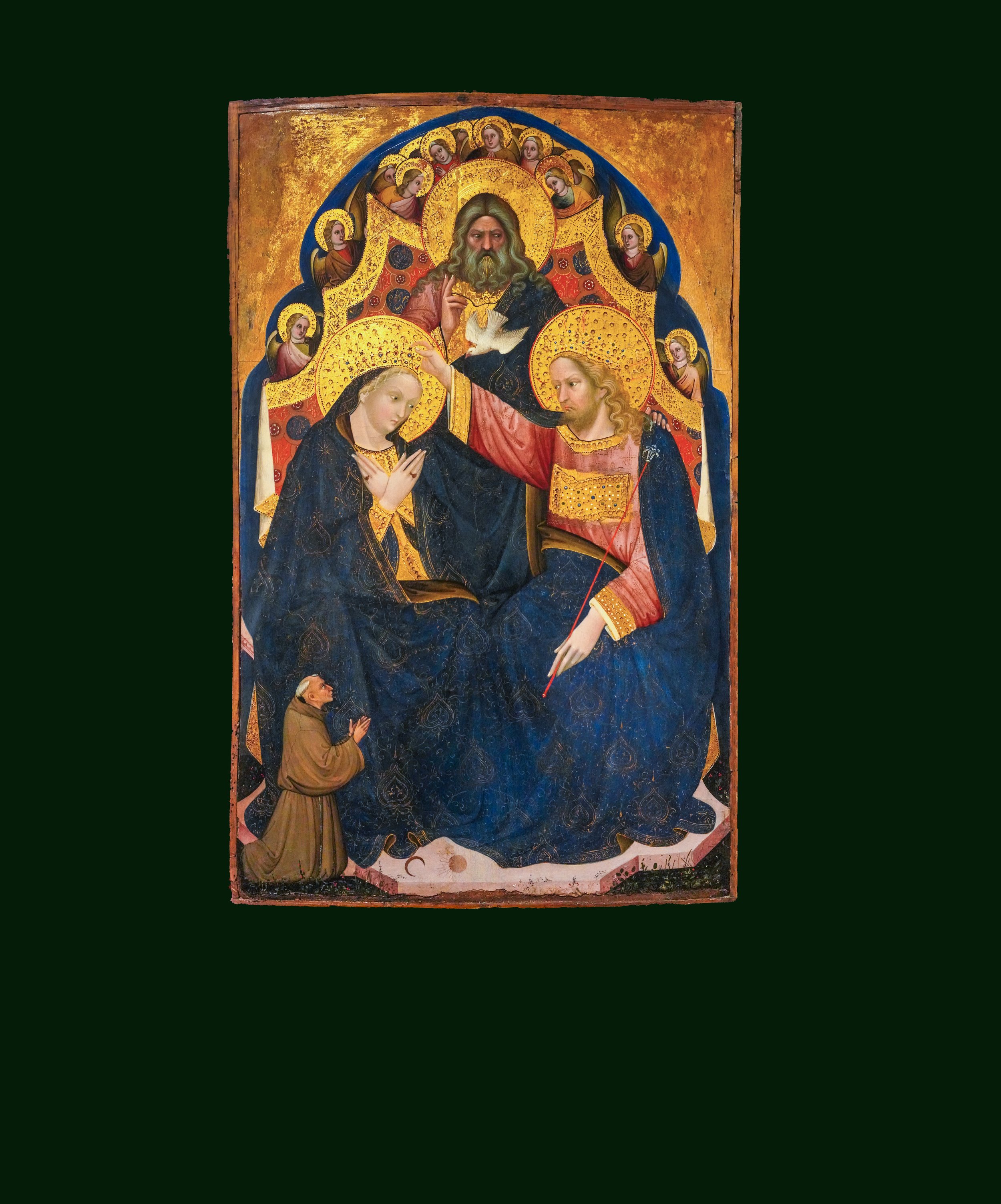

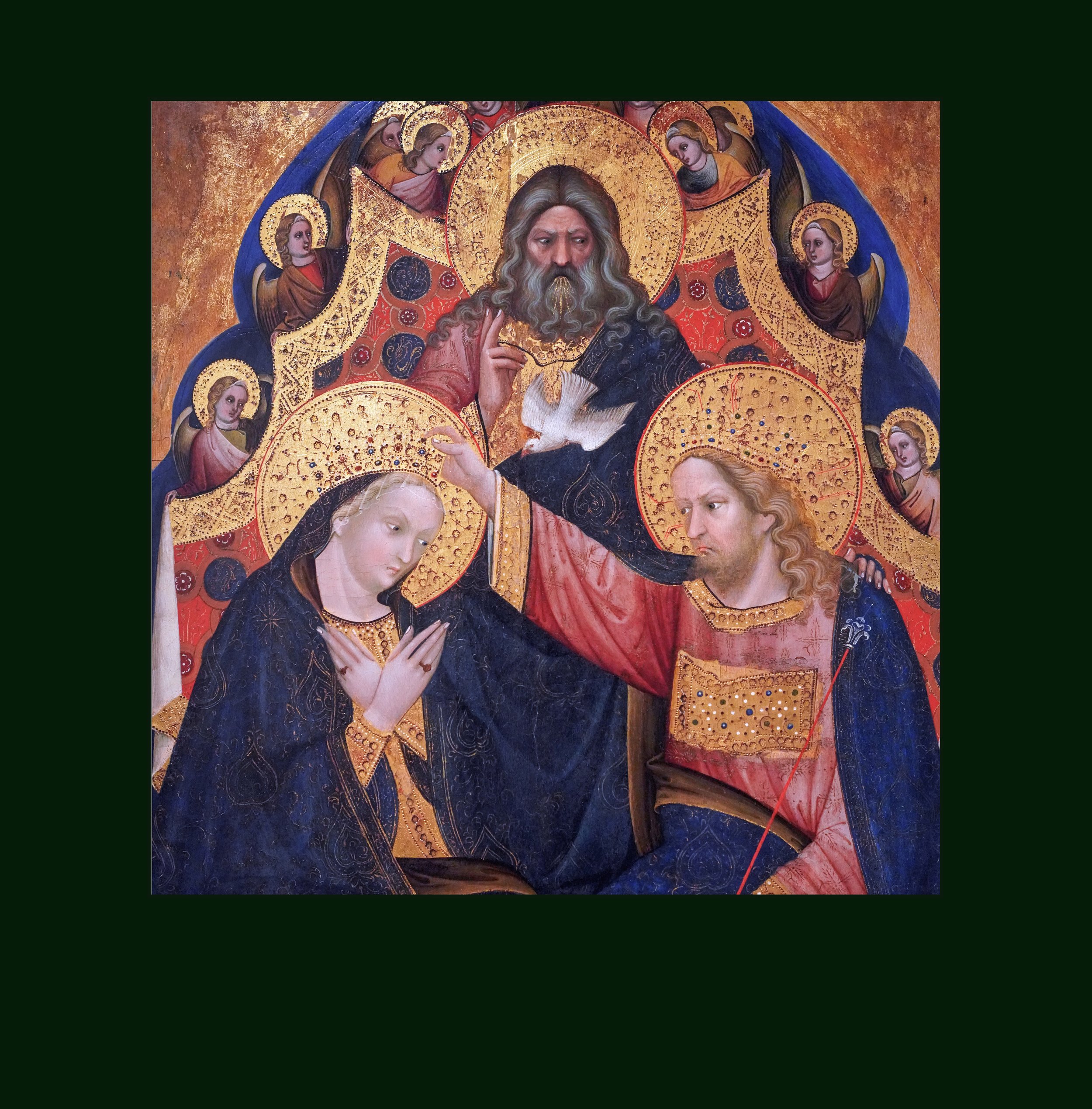

Museum label: The Coronation of the Virgin is a sophisticated example of the flamboyant style that inspired Venetian painting at the turn of the 14th c. Niccolo di Pietro’s small panel is considered a tribute to the decorative preferences of International Gothic in its most spectacular aspects. The elegant, linear rhythm of the draughtsmanship, the extremely fine handling of detail and the …abundance of gold give the picture the precious, jewel-like air of an item a goldsmith might have fashioned.

Based on the Museum label: In Niccolo di Pietro’s Coronation of the Virgin “the calligraphic treatment of the dark blue drapery, enveloping the three main figures as though in a single mantle, serves the better to highlight the delicate modelling of their faces and to illuminate God the Father’s imperious scrutiny, …Mary’s shy gaze,” Christ’s authoritative glorification, and the Holy Spirit’s unifying presence.

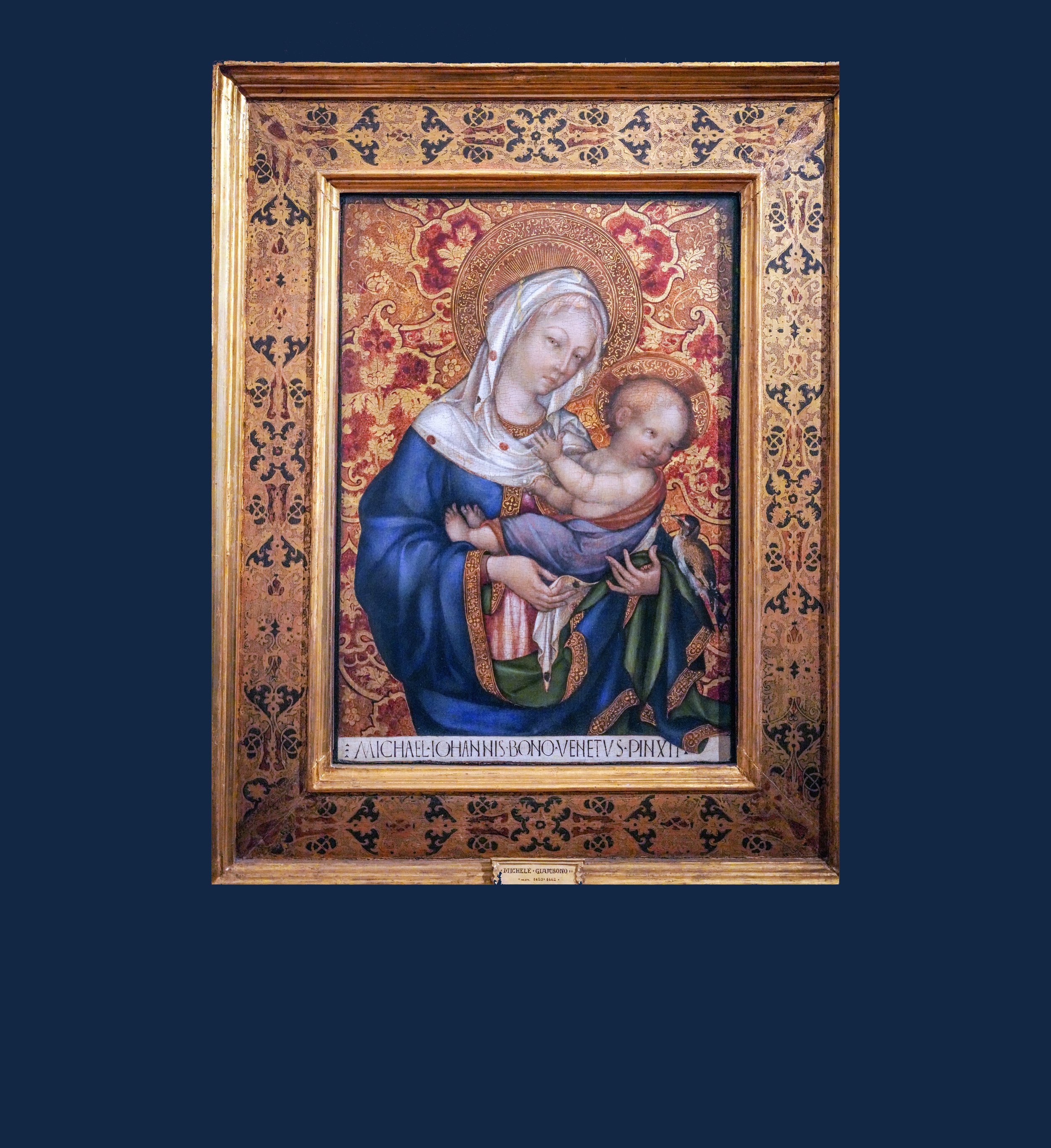

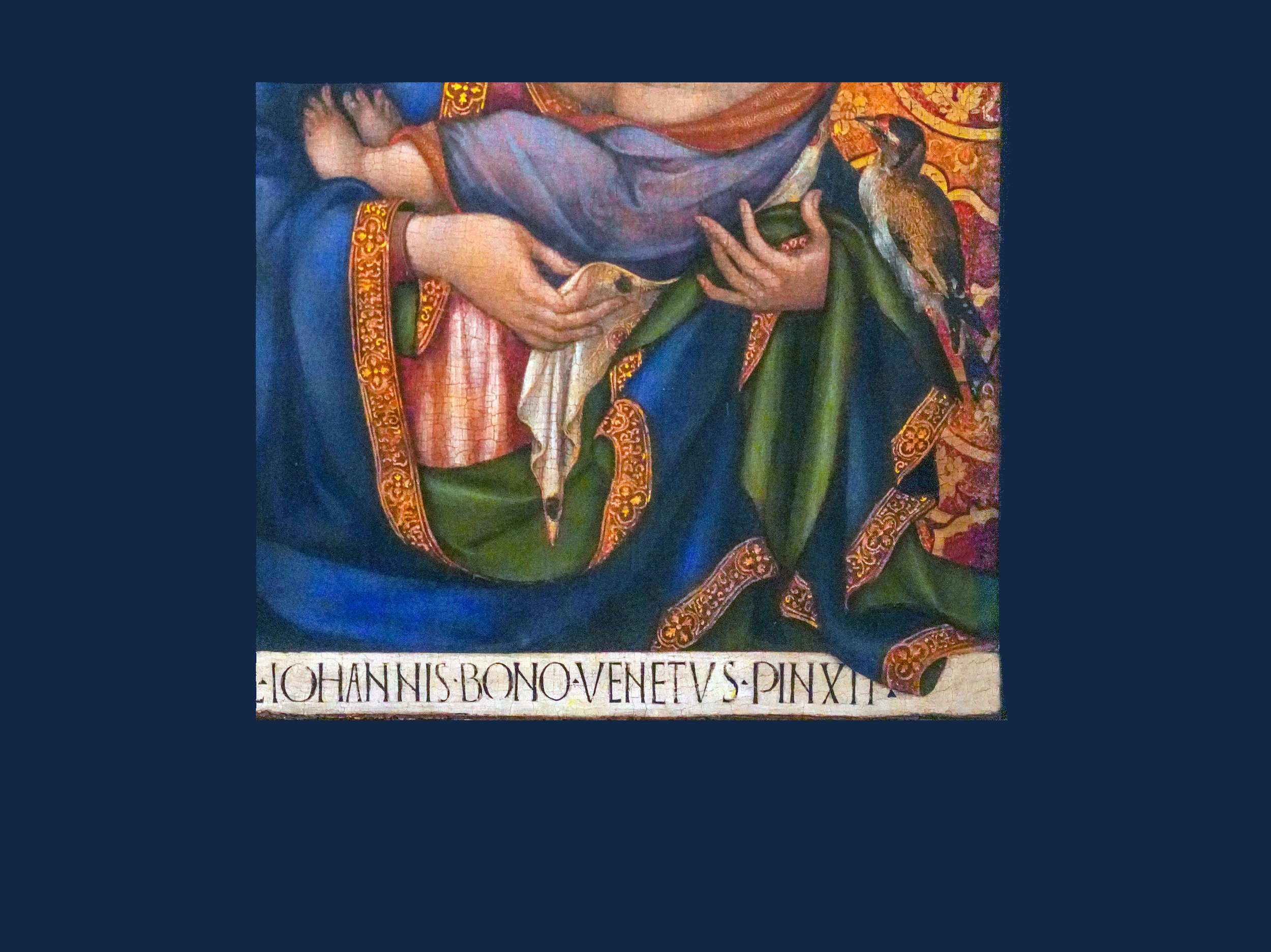

Based on Museum label: Though working in the mid-15th century, Giambono still strikes a subtle, engaging balance between the new stimuli of Quattrocento painting and the figurative tradition of the long Middle Ages. For example, whereas medieval paintings were flat with little to no shadows or hint of three-dimensionality, and the subjects were typically more serious and somber, Giambono’s Virgin and Child portrays a smiling Christ child as he looks at a goldfinch, a Renaissance art symbol of healing and redemption. Also, Giambono combines an exquisite Gothic grace of line with a sculptural sense of form in a fabric interweaving pure visual with a tactile taste for matter.

Based on Museum label (cont.): The brocade spreading out behind the figures competes with the Venetian masters' textile expertise to confer on the fabric of the image an almost tangible consistency, for instance in the gilded embroidery edging the Virgin's mantle. In contrast to the flat garments of Medieval art, the strip of her mantle that appears to emerge from the picture almost offers itself to the touch, even overlapping the perfectly two-dimensional signature at the very point where the painter's hand lays proud claim to the magic of his skill and talent.

Jean Changenet was a leading figure in Provence and Bergundian painting during the 15th c. transition from the Late Gothic style to the Renaissance. The stern figure of the Sorrowful Madonna stands out against an architectural background that already shows a grasp of perspective, but the picture focuses its intense pathos on two features: the ancient grieving gesture of the Virgin wringing her hands, and her pained face whose ashen pallor and blue lips appear to share bodily in her son's Passion.

Museum label: These panels, once part of a more complex structure, pick up the belated legacy of the art of the Flemish primitives with their typical combination of the meticulous observation of natural detail, a predilection for jewel-like consistency and widespread recourse to the codified repertoire of a ''disguised symbolism.” Thus, what prevails here are themes heralding the Passion, e.g., in the botanical symbology of the Nativity, and the fulfillment of the Sciptures, as suggested by the stories of Moses carved on the jube in the back ground of the Presentation.

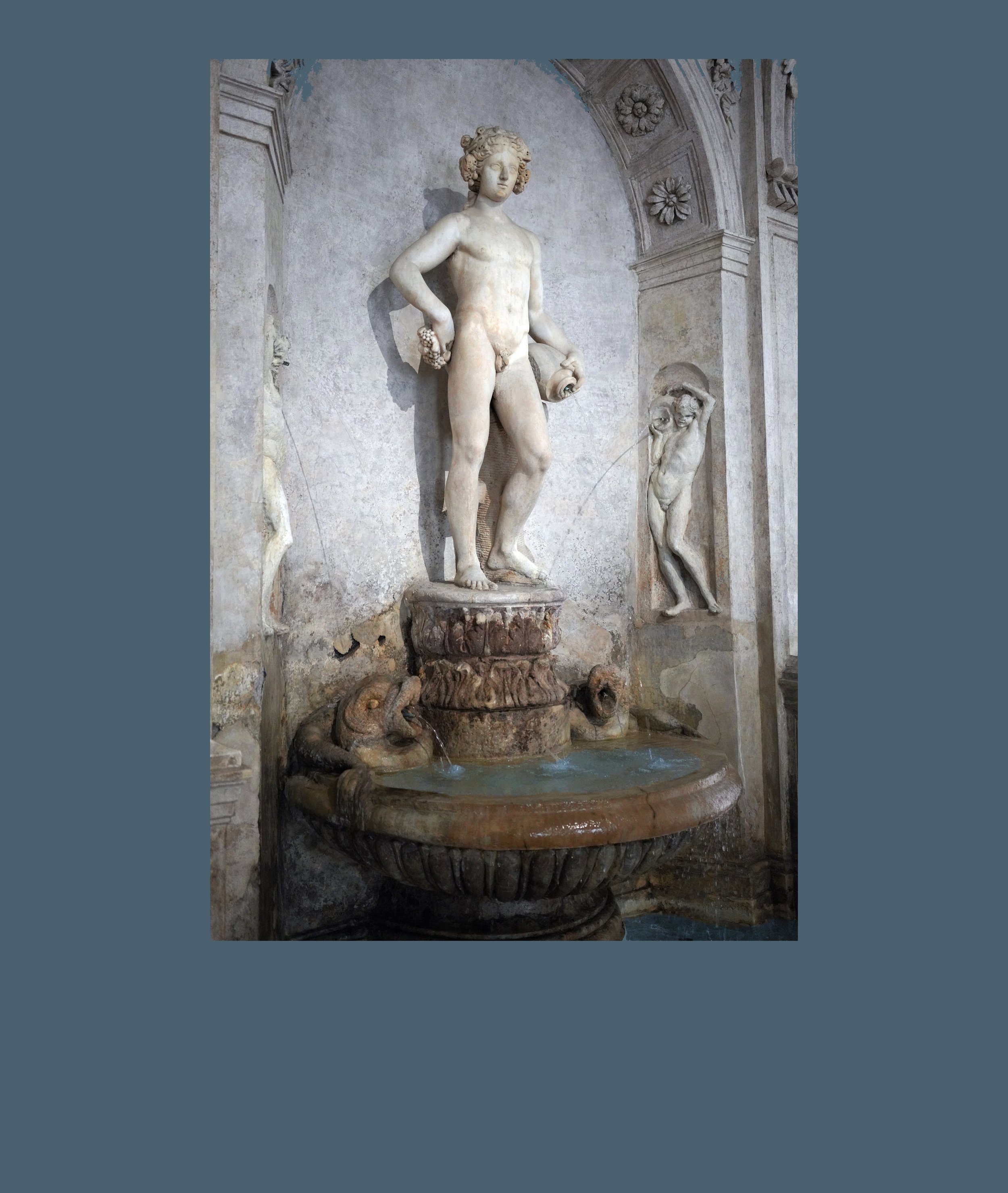

Museum label: The Room of the Columns was initially used as a “tinello”, or dining room, for the attendants of donna Costanza Magalotti Barberini (1574-1644), the sister-in-law of Urban VIII and mother of the nephews Francesco, Taddeo and Antonio. The ornamental fountain with the statue of Bacchus bears in the tympanum the joint coats of arms of the Barberini and Giustiniani families, perhaps in memory of the wedding, celebrated in 1653, between Taddeo’s son, Prince Maffeo (1631-85) and Olimpia Giustiniani (1641-1729), great-grandson of the pope Innocenzo X (1644-55).

Bacchus was the Roman god of agriculture, wine and fertility, equivalent to the Greek god Dionysus. It was said that Bacchus invented wine overseas, spreading knowledge of the cultivation of grapes and their processing into wine. He was also the patron of the arts and the protector of the theater. His festivals, the Bacchanalia, were celebrated with great enthusiasm and often involved wild, ecstatic revelry.This statue contains symbols of Bacchus, such as his crown of vine leaves, the wine grapes in his right hand, and the amphora (wine container), from which water flows, in his left.

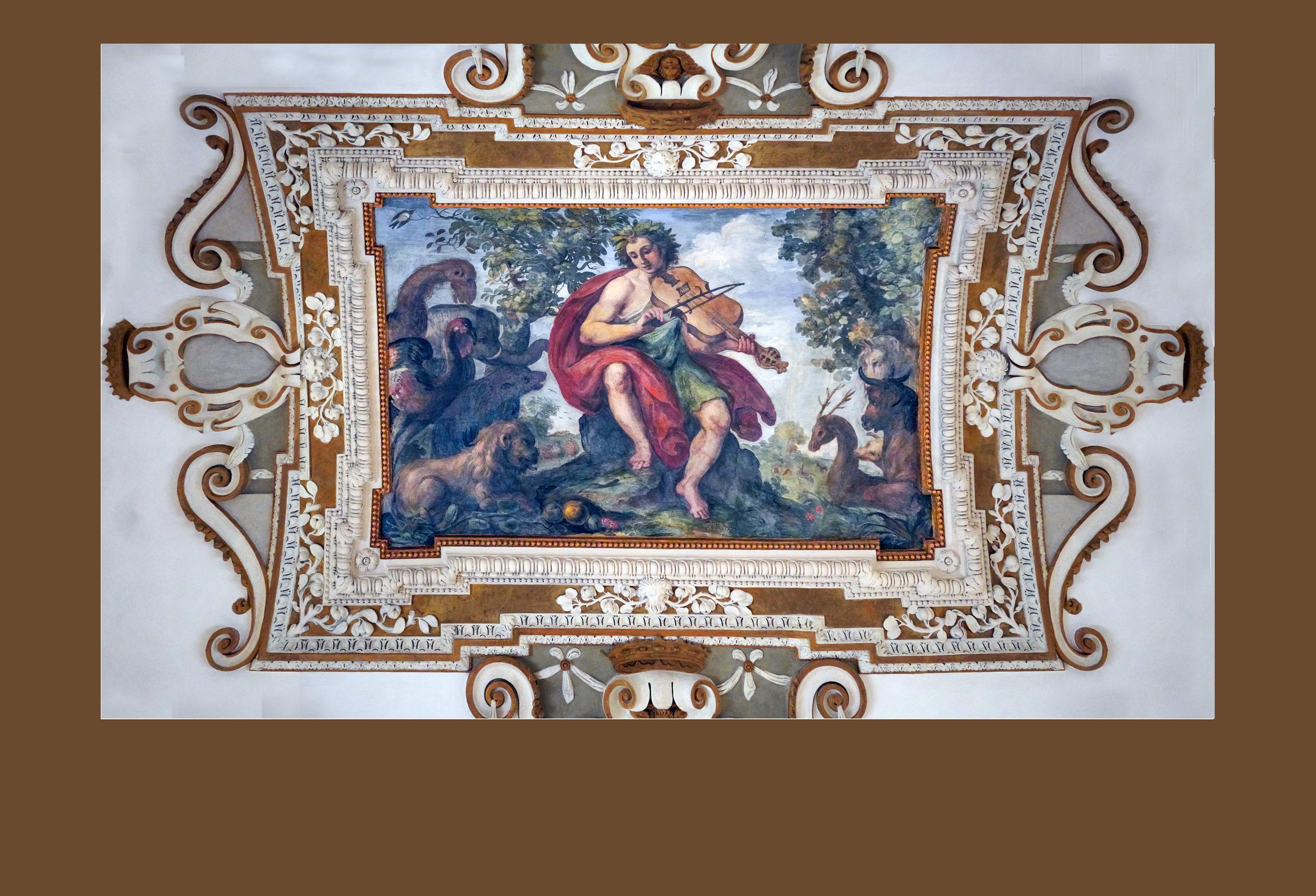

In Greek mythology, Orpheus was a poet and musician who could tame animals with his music. The god of music, Apollo, gave Orpheus a lyre, and the Muses taught him to play it. Orpheus's songs and playing were so beautiful that they could calm the seas, animate rocks and trees, and even pacify wild animals. The scene in which Orpheus tamed the wild animals by his music was well known in the Roman imperial time. The idea of civilizing barbaric traits through arts and poetry was a persistent cultural value throughout Roman times. It is a symbol of the victory of the civilization over barbarianism.

In Frediani’s Virgin and Child between Saint Peter and Saint Paul, on the left of the Virgin and Child, Saint Peter holds the papal keys in his hands, while on the right Saint Paul holds the sword with which he was martyred and a book representing his epistles. The image thus confirms that the authority of the Church was granted by Christ himself, a central tenet of the Counter-Reformation. Vincenzo di Antonio Frediani, an Italian Renaissance painter, was probably trained in Lucca but in the 1480s fell under the influence of Domenico Ghirlandaio and Filippino Lippi, and Sandro Botticelli. His composition, in particular, owes much to Lippi.

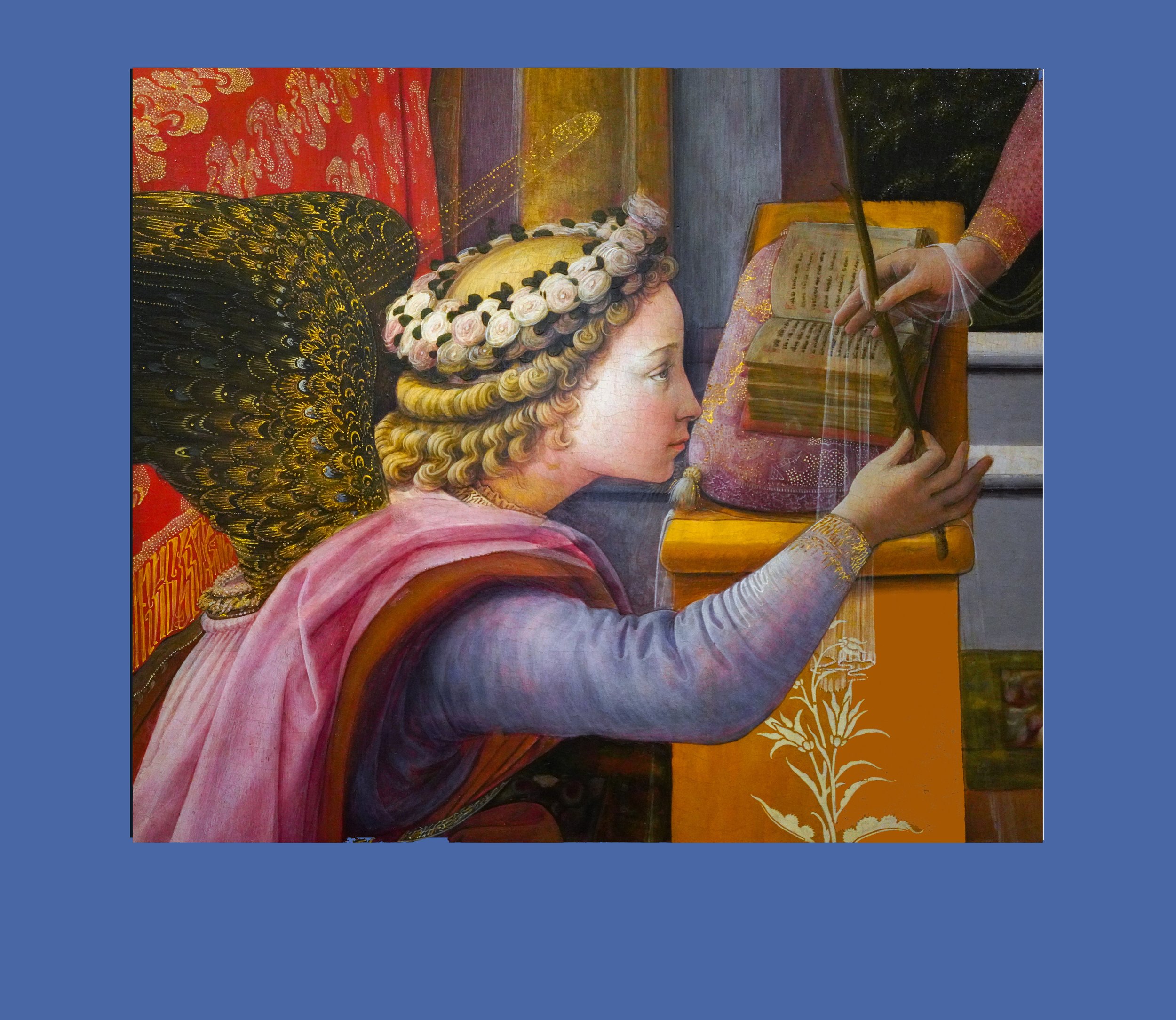

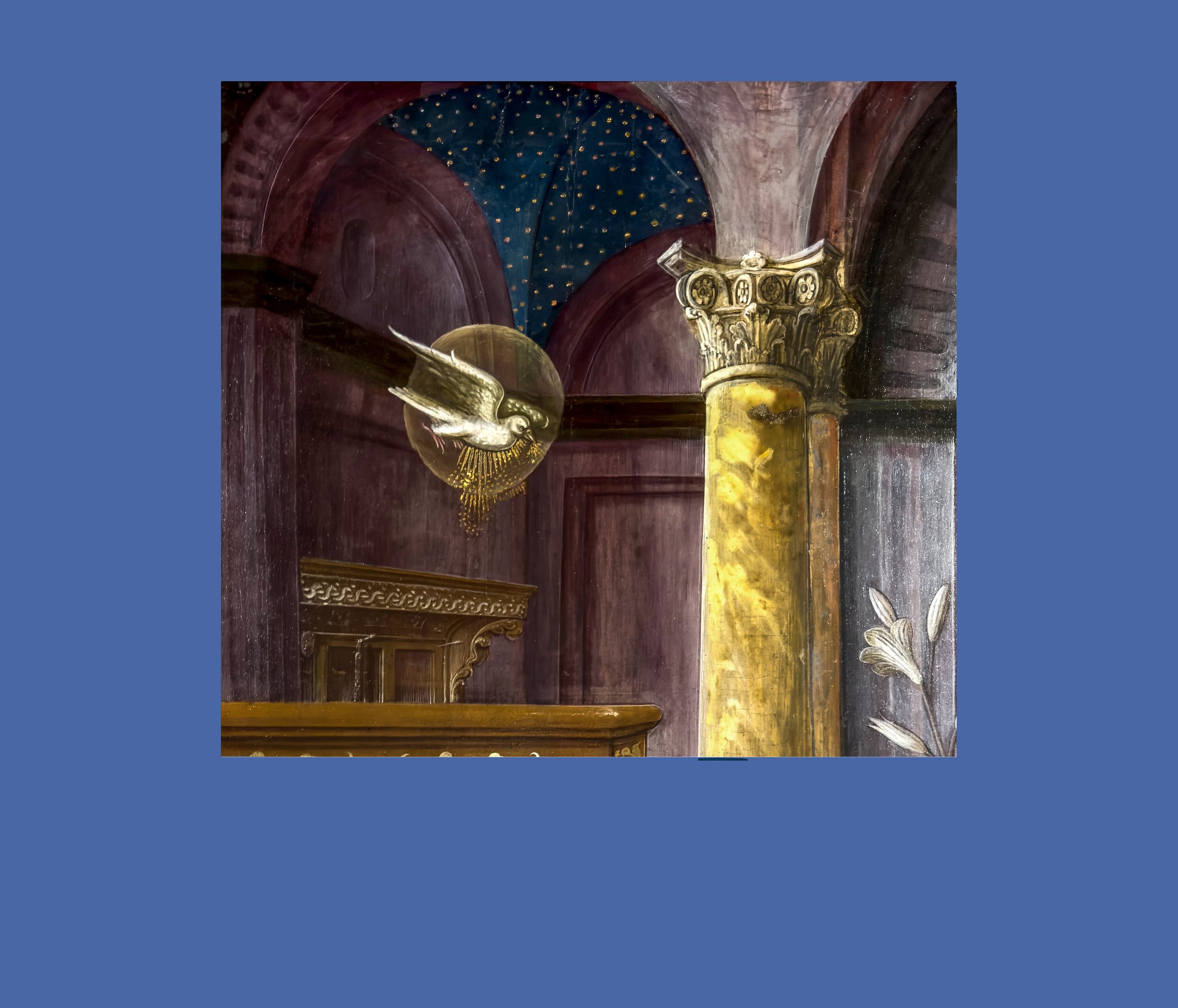

The Annunciation is the announcement by the archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and give birth to Christ. It is important in Christian belief because with Jesus’s Incarnation (being made flesh) comes salvation for all mankind’s sin, with his eventual death on the cross. The task before artists was to envision the Annunciation story in pictorial form, and so a convention of symbolism was developed to make the “mystery” of the Annunciation, legible to the largely illiterate medieval worshipper. For example, Mary's virginity and spiritual purity are symbolized by the lilies Gabriel gently hands to her, while Mary herself becomes symbolic perspective, a point of transition and mediation like the gossamer curtain descending onto the bed, a metaphor for the "veil of the flesh" or the human nature embraced by Christ.

In Lippi’s Annunciation, Mary's home includes an airy loggia with classicizing columns and capitals opening out onto a space with a hortus conclusus or closed garden, further alluding to the Virgin's miraculous conception. Also, Lippi inserts an opened book on a stand, an image derived from the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew that comments on the Virgin reading: “She was always engaged in prayer and in searching the law” (Chapter 6). The iconography of the book was used to reference, and was sometimes depicted open at, Isaiah’s prophesy: “And the Lord himself shall give you a sign. Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14). This was interpreted from the early medieval period as a prediction of the birth of Jesus.

In Lippi’s Annunciation, Gabriel kneels before Mary, an image derived from a courtly feudal custom of kneeling before a lady, and with his brilliant, gold-gilded wings, he says, “Rejoice, highly favored one, the Lord is with you; blessed are you among women!” But when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying…. Then the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. And behold, you will conceive in your womb and bring forth a Son, and shall call His name JESUS. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Highest; and the Lord God will give Him the throne of His father David. And He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of His kingdom there will be no end” (Luke 1:26-48).

After Gabriel announced to Mary that she would have a child, Mary said to the angel, “How can this be, since I do not know a man?” And the angel answered to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Highest will overshadow you; therefore, also, that Holy One who is to be born will be called the Son of God…” (Luke 1:26-48). Lippi presents the Holy Spirit descending over Mary’s bed while Gabriel and Mary hold lilies, both images symbols of Mary’s purity. Lippi’s dove represents the Holy Spirit on its journey to make God incarnate as Christ, emissus caelitus (“sent from heaven”, and therefore not formed in the uterus).

In Greek and Roman mythology, Orpheus’s attempts to bring Eurydice back to life after she dies. Orpheus is lyre player and poet whose music is so divine that it moves animals, trees, and stones, and calms the seas Eurydice is a beautiful nymph who dies from a snake bite on her wedding day. Grief-stricken, Orpheus travels to the Underworld to try to bring her back. He encounters Hades, the king of the underworld, and his queen Persephone, and plays music so beautiful that it moves them to tears. Hades allows Orpheus to take Eurydice back to the living world, but on the condition that he not turn around as she follows him out of Hades. However, Orpheus, in a moment of weakness, turns to see if Hades has fooled him, and thereby fails to follow Hades’ instructions, thus losing Eurydice forever.

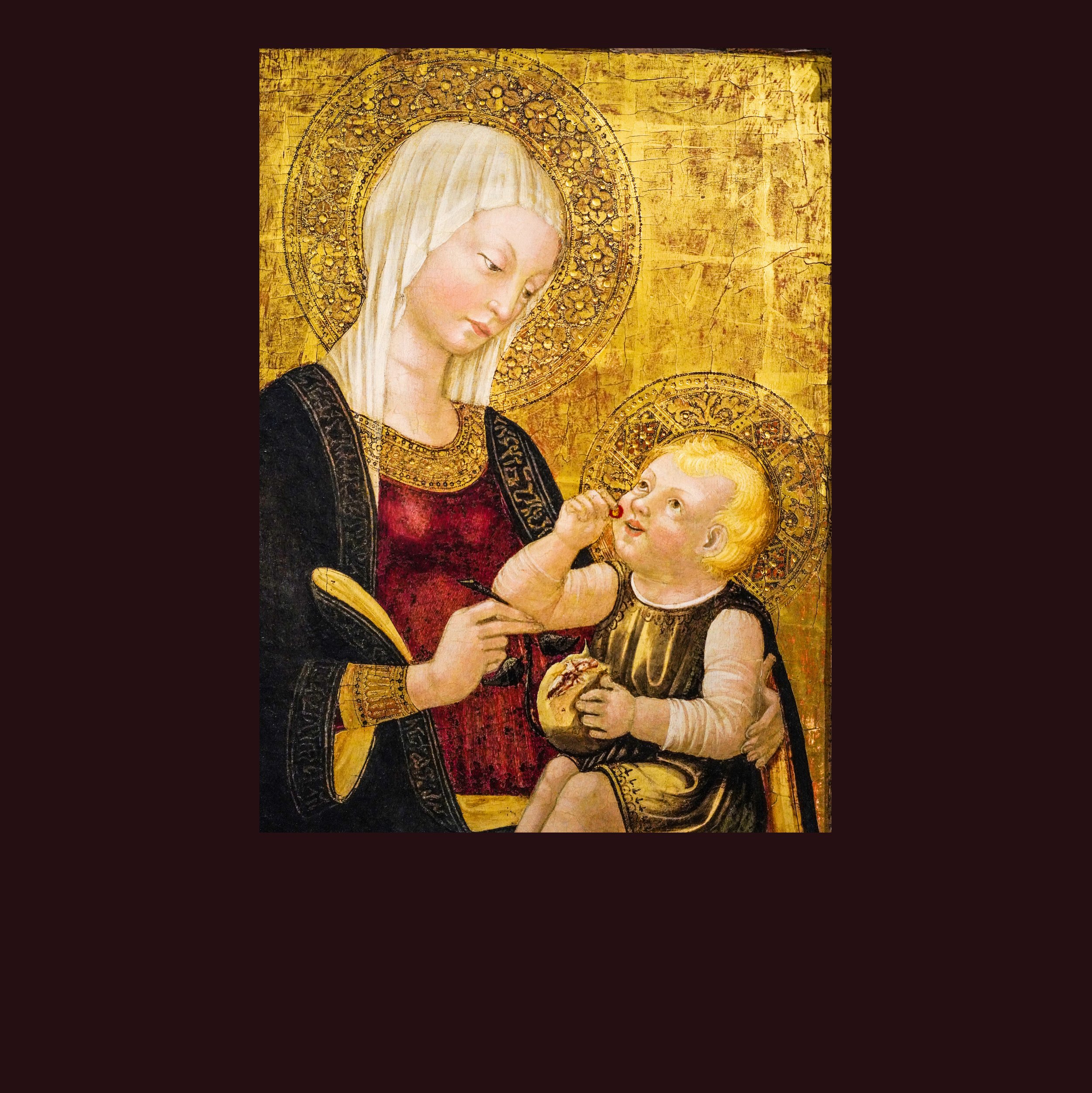

Based on museum label: Small devotional images, often in the shape of a tabernacle, known as "colmi da camera" and generally depicting "Our Lady", were still very much in demand on the art market in Florence throughout the 15th century. Neri di Bicci's workshop produced an enormous number of these images and this small painting must have been one such, with its extremely traditional iconography of the Virgin in a half-bust pose enhanced by the gold background, the elaborate arrangement of haloes and pseudo-Cuphic motifs adorning her mantle. The variant here is the pomegranate, hinting at the Messiah’s sacrifice and eventual resurrection.

In Christian art, the pomegranate's red seeds represent the blood Jesus shed for humanity's salvation. Also, the pomegranate symbolizes the transition from life to death and resurrection, as the seeds will eventually be reborn. The act of opening the pomegranate's rough peel and harvesting the seeds has been described as a metaphor for the Passion of Christ, where suffering reveals an abundant treasure. In di Bicci’s Virgin and Child, while the Christ child looks up to his mother smiling, as if to say all will be well, she looks down at him with lovingly with the knowledge of his suffering and death.

Museum label: In this small picture designed for domestic devotion, Gherado appears to be up to date with the stylistic developments in the contemporary Florentine art of Ghirlandaio, Leonardo and Botticelli. The scene of silent, contrite prayer is enlivened by Jesus’s gesture as he turns knowingly to his mother, grasping her symbolic veil - a symbol of the human nature that Christ inherited from his mother as well as their loving bond. In the background, in a perspective at once spatial and temporal, we see the tiny pinnacle of a church that still lay in the future but that was already present in figurative terms.

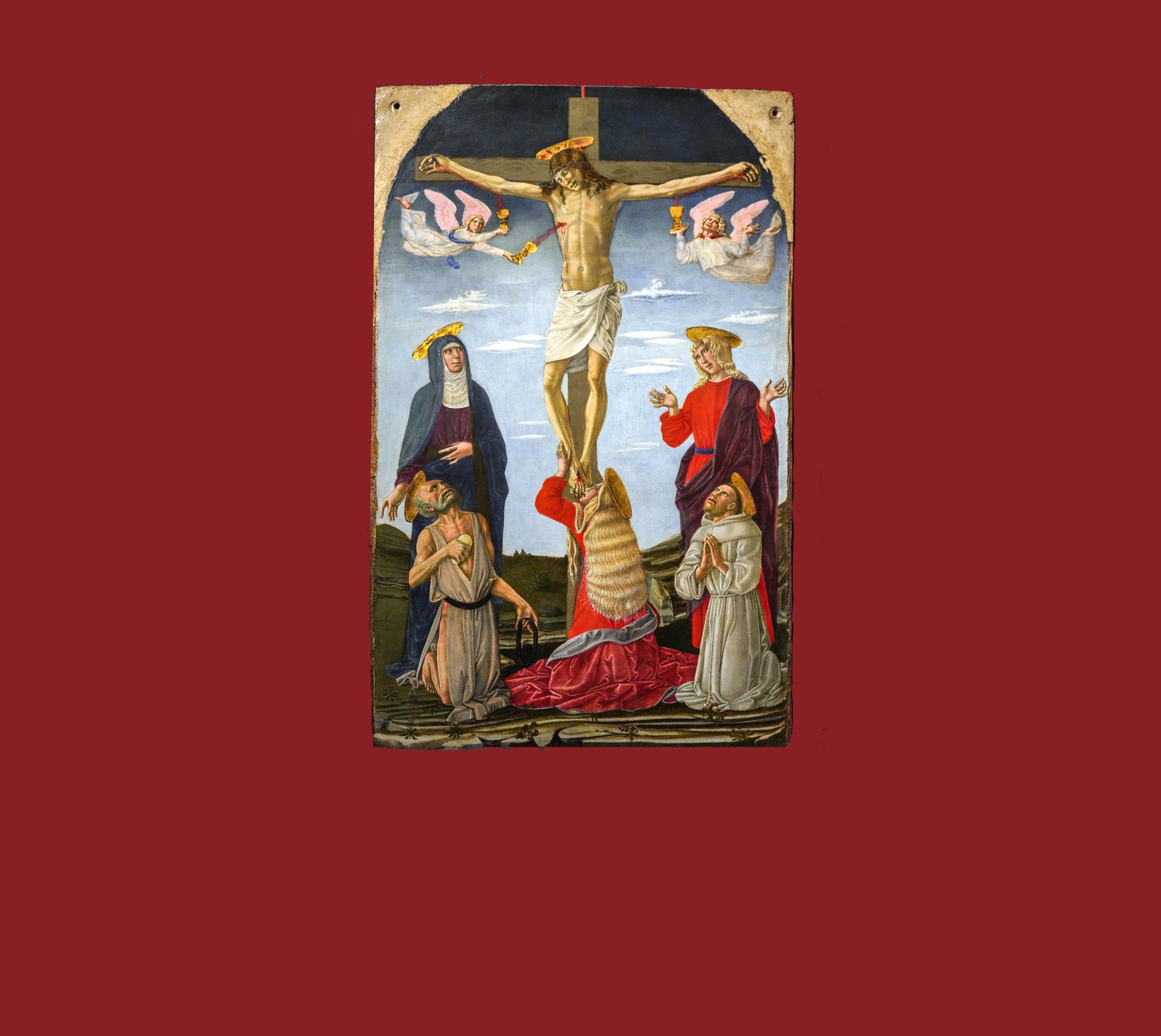

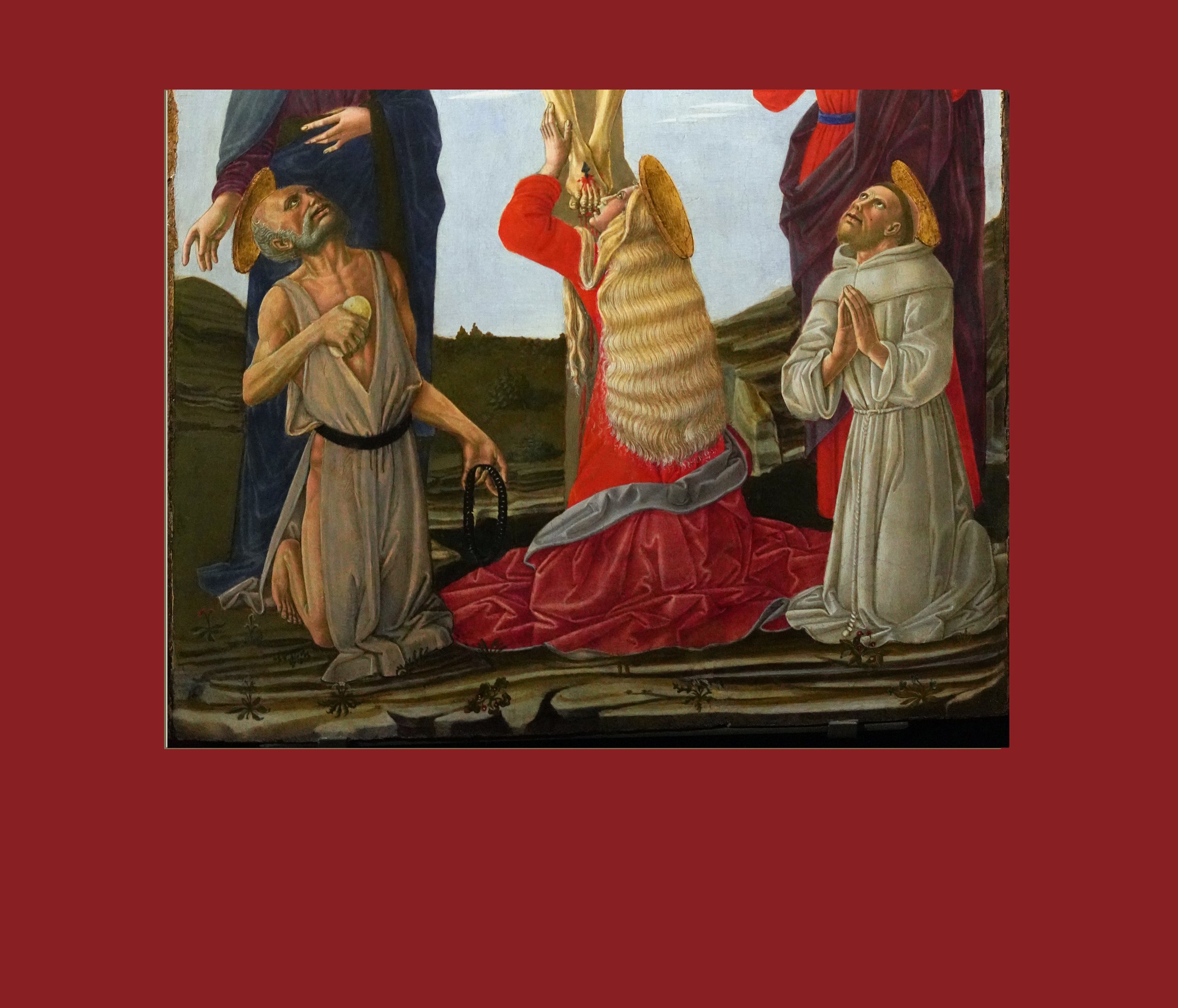

The Crucifixion depicts a bleeding, dying Christ on the cross, with St. Jerome on the left and St. Francis on the right kneeling as witnesses to the horror. In the middle of the painting, Mary Magdalen, with her blond hair undulating down her back, touches Christ’s leg above his bleeding, nailed feet, causing her scarlet garment to absorb its color as the anguish flows through her. Angels flying around the bleeding Christ catch the drops of the Precious Blood in chalices as they fall from the sacred wounds. According to Hebrews 9:22, “Indeed, under the law almost everything is purified with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.” Thus, it is believed that Christ's wounds were channels through which his blood was spilled, sealing a new covenant and destroying the power of sin and death over humanity.

Based on Museum label: This small painting was an exponent of the particular school of Sienese Renaissance in which the new conceptions of figurative space and the influence of classical culture were filtered through a lasting interest in the liveliness of incisive draughtsmanship and a jewel-like palette. Benvenuto’s drapery's jagged folds in the robes of Magdelen, Jerome and Francis appear to mirror the craggy fault lines and rough crevices of Golgotha, so that the image takes on an almost crystalline aspect, as clear as the light that illuminates the tragic scene without making any allowances for soft, atmospheric velature.

In Ulysses Encounters the Sirens Giacinta Camassei provided the 17th century residents of the Palazzo with a mythological figure embodying the Christian cardinal virtue of Temperance. In Homer’s The Odyssey, Ulysses and his crew encounter the Sirens while returning home from the Trojan War. The Sirens are beautiful, half-woman, half-bird creatures who lure sailors to their island with their enchanting songs. The songs are so hypnotic that they can cause sailors to crash their ships on the rocks. To avoid the Sirens, Ulysses instructs his crew to plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the ship's mast. He tells them to ignore him if he tries to follow the song, and to keep their swords ready to attack him if he breaks free. When they hear the Sirens' song, Ulysses struggles to break free so he can join them, which would mean his death. However, his men remain faithful and refuse to release him, and the crew is able to safely sail past the Sirens' island.

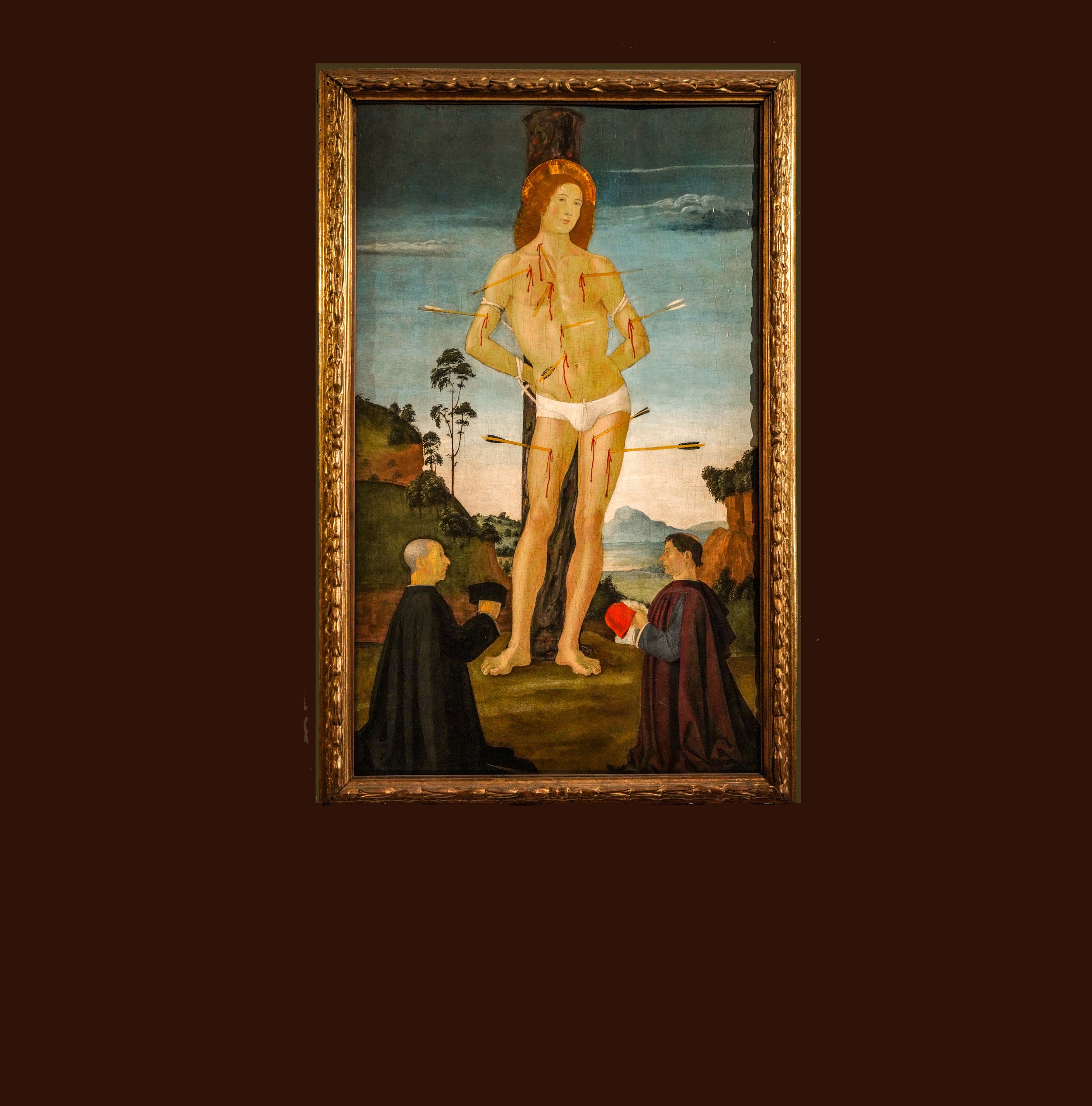

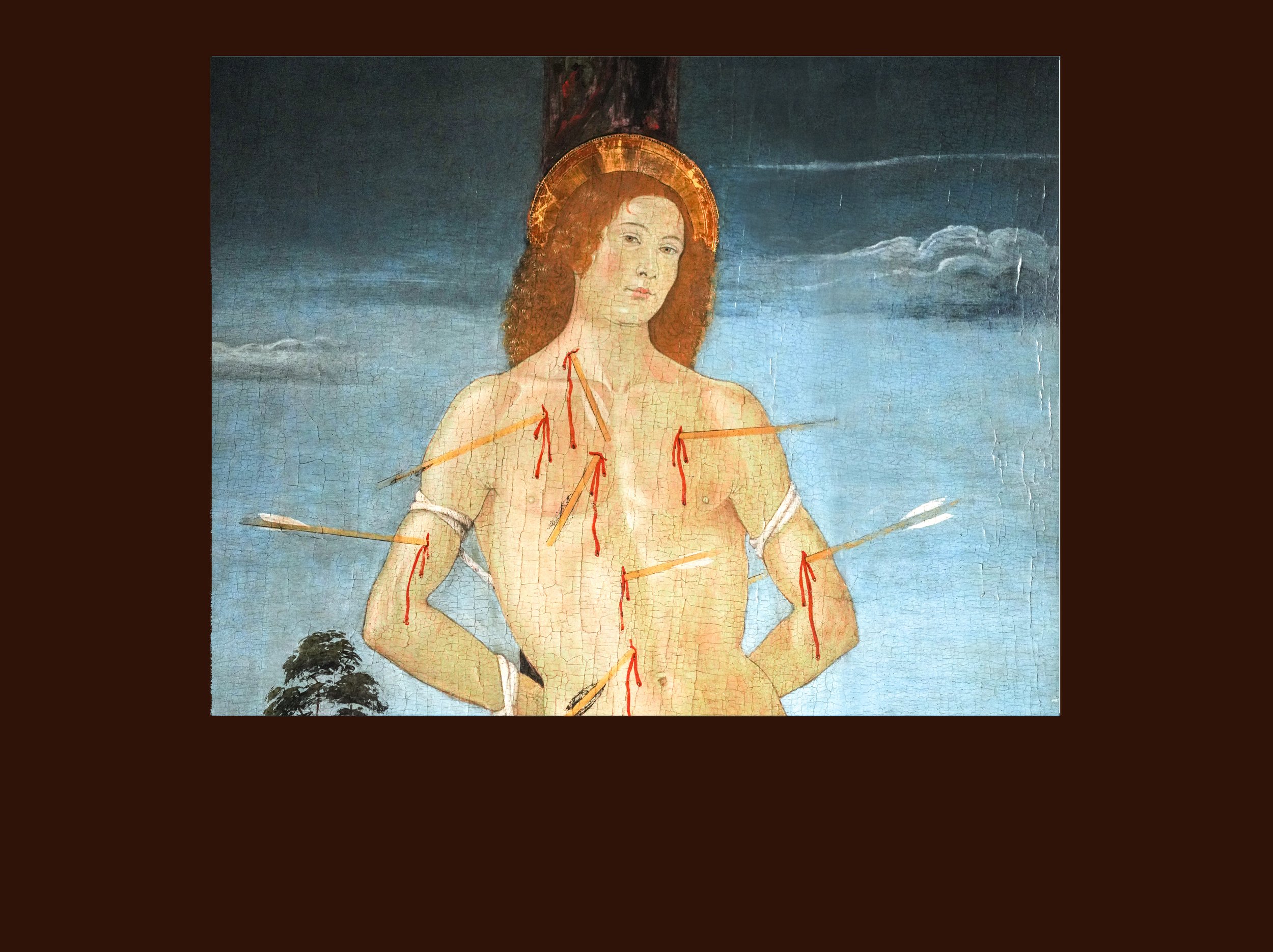

Based on Museum label: This altarpiece of clearly votive inspiration avails itself of the legacy of medieval figurative convention, evidently on account of the function for which it was conceived. The figure of the martyr St. Sebastian, invoked in popular tradition against the plague and other epidemics, is shown here in the guise of a protector seemingly insensible to his own suffering, bound to a column which, though in variegated marble, nevertheless stands in a natural setting. There is a glaring difference in scale between the miracle-working saint and the two donors genuflecting at his feet, …tentatively identified as Onorato II Caetani d'Aragona, Count of Fondi, and his son Pietro Bernardino, devoutly portrayed using the time-honored formula of the perfect profile.

According to tradition, St. Sebastian (AD 255 – c. AD 288) was ordered by Diocletian to be killed with arrows for converting fellow Roman soldiers and prisoners to Christianity. He was left for dead by the archers but when the widow, Irene of Rome, went to retrieve his body to bury it, she discovered he was still alive, and nursed him back to health. Afterwards, he confronted Diocletian to warn him about his sins and admonish him for his treatment of Christians. As a result, Diocletian ordered him clubbed to death and his body thrown in a common sewer. A holy lady named Lucina, privately removed the body and buried it in the catacombs where now stands the Basilica of St. Sebastian. In pagan belief, pestilence was delivered by arrows shot from above by the gods. When a virulent epidemic swept through Rome in A.D. 680 the populous prayed for Sebastian to intercede, as he had survived being skewered with arrows. In addition, he had become a Christological figure, his body having been bound, pierced, and rescued from death, experiencing a form of Resurrection.

Museum label: This altarpiece, signed and dated by Antoniazzo, was painted for the Franciscan church of Poggio Nativo near Rieti. It is typical of the work of this Roman painter who, possibly bowing to the demands and preferences of his patrons, showed no compunction in resorting to age old, traditional stylistic features and formulas, yet without foregoing the elements of a more modern style. Here, the gold ground against which the figures stand out and the overall composition of the Virgin and Child still echo the hieratic quality of icon painting, with which Antoniazzo was familiar, yet the saints fill the space with solidity while the Virgin's fanciful throne hints at a sophisticated contemporary taste for classical antiquity.

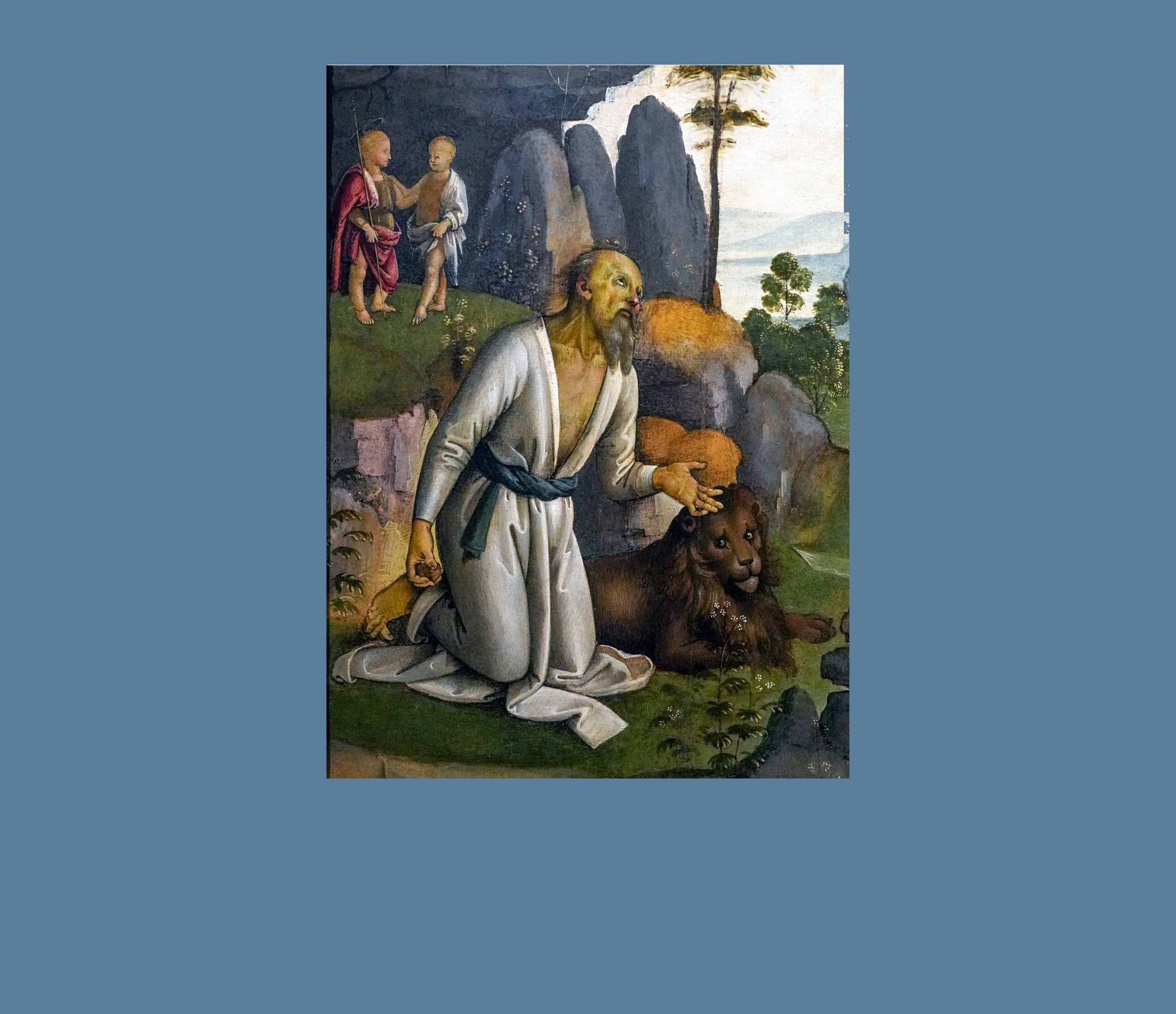

St. Jerome in the Wilderness, attributed to Perugino, revisits an iconographical motif fairly frequent in 15th and 16th century Italian painting, depicting St. Jerome as a penitent hermit fleeing the insidious temptations of the world, embodied here in the walled city in the distant background. Also, St. Jerome is shown accompanied by a lion. According to legend, during a visit to the wilderness near Bethlehem, St. Jerome met a lion that had a thorn in its paw. Rather than fearing the animal, he took pity on the lion and removed the thorn, and the lion became his devoted companion.

Il Perugino’s image, St. Jerome in the Wilderness, offers visual support for ascetic meditation. During his time of religious contemplation, Jerome was tormented by vivid temptation-filled hallucinations; Perugino’s Jerome clasps a rock in his right hand with which he would beat his breast until the visions passed. The image also points up the exemplary value of imitation, because the aging Jerome is literally following in the footsteps of an …illustrious hermit, the precursor John the Baptist. The Baptist is seen here in the left background when, according to a popular if apocryphal legend, he withdrew into the desert while still a boy and there had the privilege of meeting the boy Jesus on his return from the flight into Egypt.

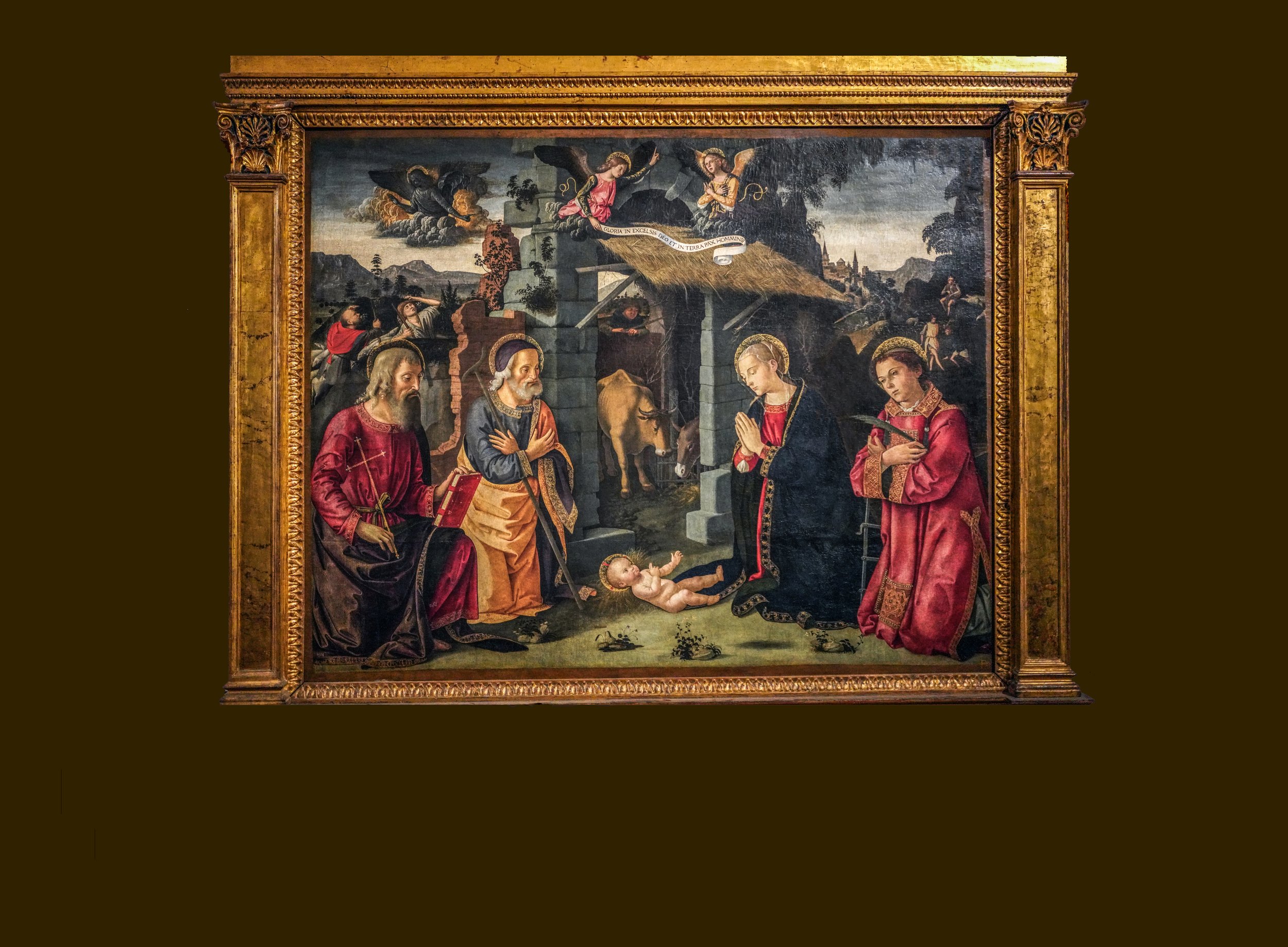

One of the most interesting aspects of this painting is its artistic style. Antoniazzo Romano was one of the first Italian artists to adopt the Renaissance style and integrate the novelties in late 15th century northern European art which was characterized by realistic representation of the human figure and perspective. In this painting, we can see how the artist uses the technique of light and shadow to create depth and realism in the scene and presents symbolism focusing on Christ's Passion. Two angels at the top of the structure unfurl the banner “Gloria in excelsis deo et in terra pax hommine”, (Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men), while a dark angel frightens the fieldworkers in the left background, reminding viewers of the eventual Passion of Christ.

Antoniazzo Romano’s Nativity is full of iconographic images, e.g., the infant Christ lying on a bundle of grain - a reference to Eucharistic symbolism - also the anemone and cyclamen in the foreground, both flowers that symbolize the Passion of Christ. In concert with the Passion, Antoniazzo includes St. Lawrence kneeling on the right holding a palm branch, a symbol of martyrdom, and St. Andrew, also a martyr, kneeling on the left holding a long cross, a reference to his martyrdom. Christ is blessing Mary with his right hand, while Joseph’s gesture of his arms crossed over his chest symbolizes his offering himself in humility as a servant of the Lord.

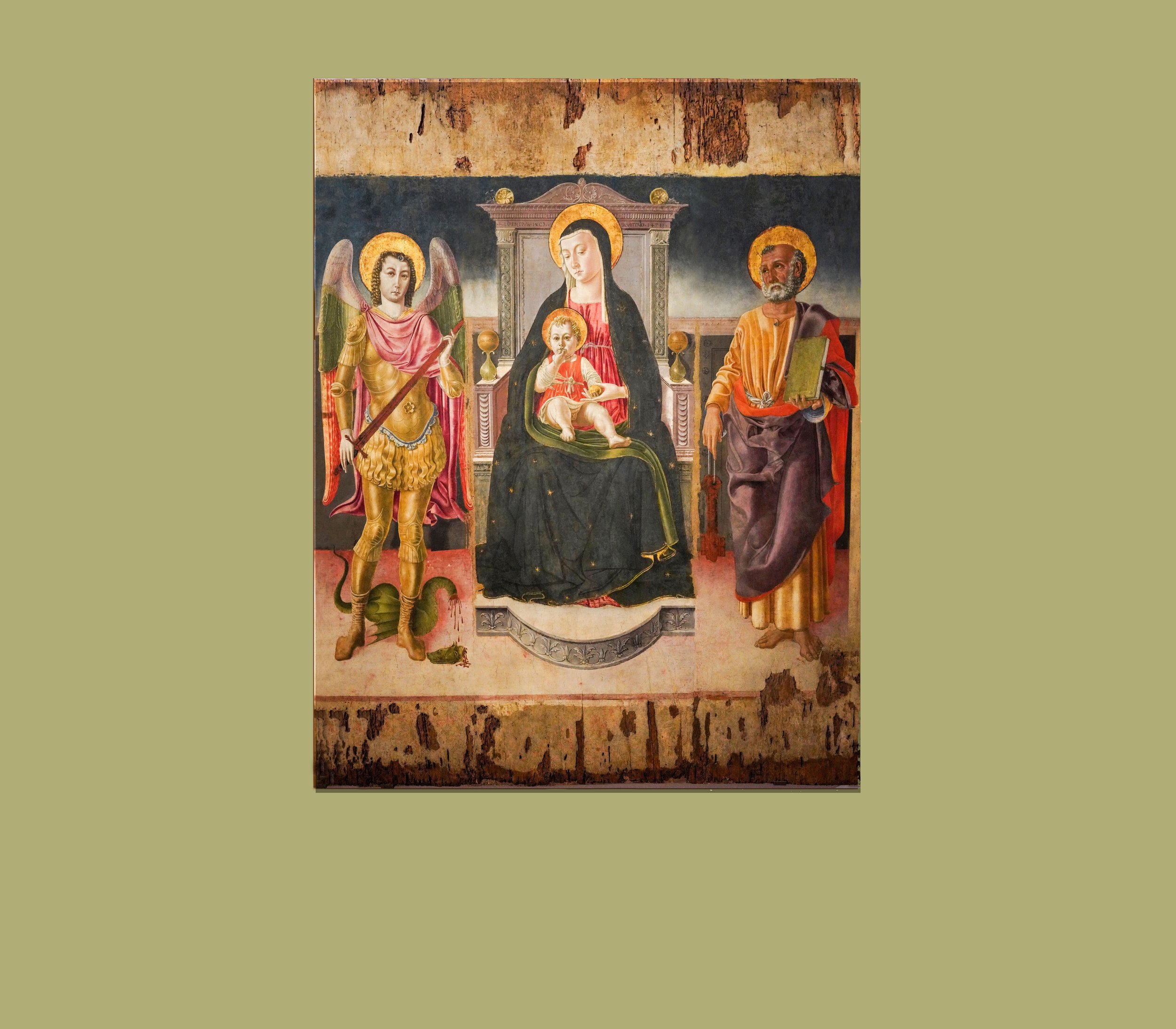

Iconography: The Christ child eats from a yellow pomegranate while holding it in his left hand, In Christian art the fruit was considered a symbol of resurrection, and a symbol of Christ's passion, whose red kernels symbolize the blood shed by Jesus Christ for the salvation of humanity. The color yellow symbolized the anointing of God, unending faith, holiness, joy, happiness, and optimism. On the left, the Archangel Michael wearing the armor of a 15th-century knight, is represented as defender of the Church against the devil, here symbolized by the dragon. On the right, St. Peter holds the Papal Cross Keys, the symbol of the Papacy, referring to the promise of Christ to Peter, “I will give you the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in Heaven.” (Matthew 16:19). I think Lorenzo’s image informs that Christ brought a message of optimism to humanity by providing a path to eternal life through his own sacrifice and through the protection and teaching of his word on earth via the Christian Church.

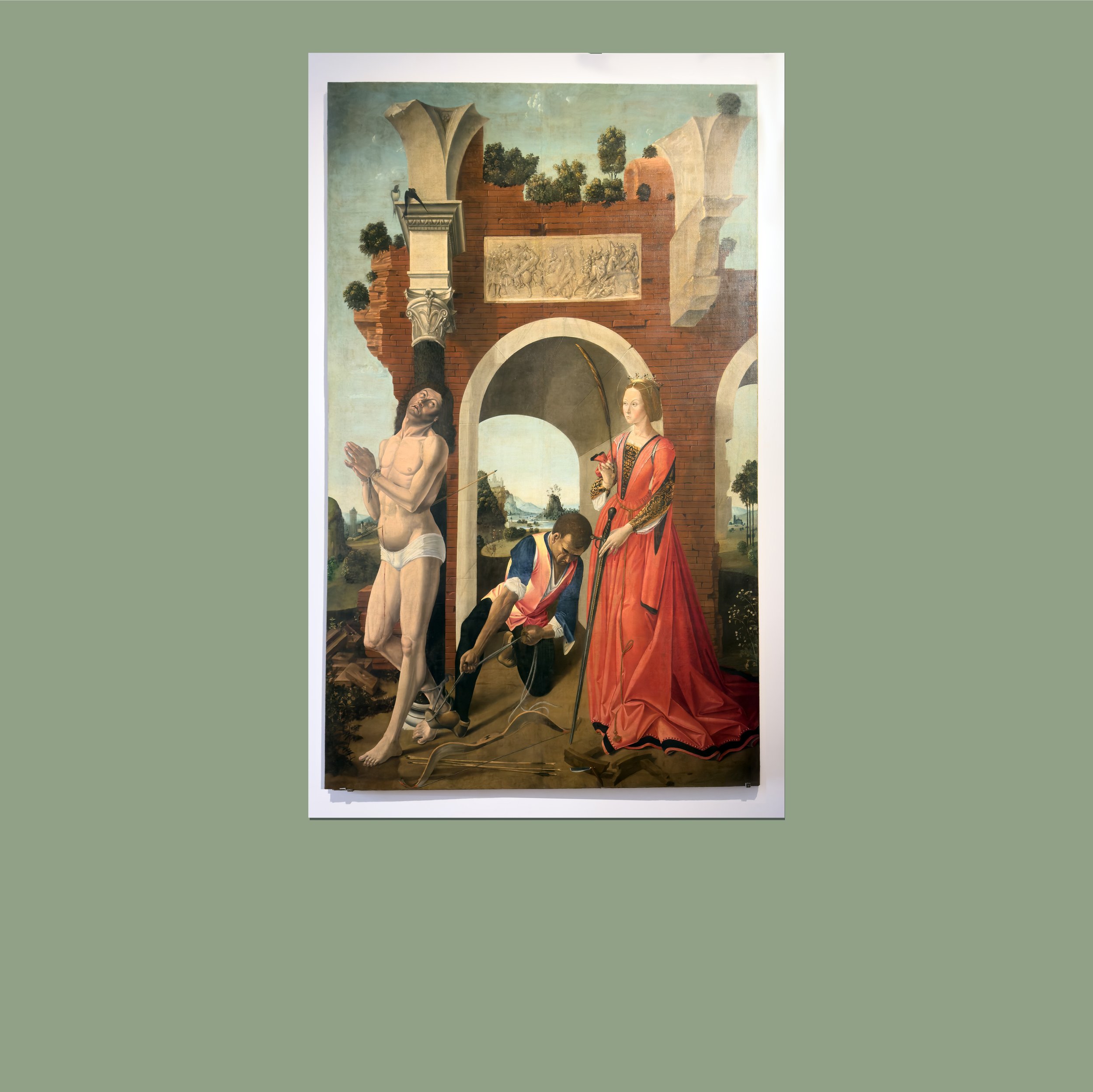

Museum label: A setting of architectural ruins set in a sweeping, luminous landscape frames the three figures in this monumental, vertical canvas which probably began life as an organ door. The sacrifice is already taking place, as the battle scene in the imitation marble relief (above the arch) seems to suggest: in the center, a jailer binds St. Sebastian with ropes as the saint, his hands joined in prayer, lifts his gaze to heaven to invoke God the Father's succor. On the right, St. Catherine of Alexandria holds the palm branch and sword of her martyrdom, both symbolizing her militancy in the defeat of paganism.

The Archangel Gabriel indicates the heavenly court to Amadeo kneeling in prayer. Christ and the Virgin, framed by a seven-pointed diadem, sit on the highest podium surrounded by a group of angels, below whom are figures from the Old (right) and New (left) Testaments. In the center, St.Joseph and St.John the Baptist serve to link the two groups. The heavenly temple architecture is clearly inspired by Donato Bramante, author of the temple built on the Janiculum Hill, at the legendary site of the crucifixion of St. Peter. Leonardo's influence is evident in the study of the figures' features and in the sweeping, atmospheric landscape which may have been inspired by the hermitage of S. Michele Arcangelo area.

This narrative of Amedeo’sVisionis derived from the Apocalypsis Nova, the report shown at his feet, in which he wrote about his ecstatic trances and his dialogues with the Archangel Gabriel. The panel is an accurate figurative transcription of the first of these visions in which Amadeo (c a. 1420-82) ascends to appear before Christ, who directs him towards the more obscure mysteries of the faith.

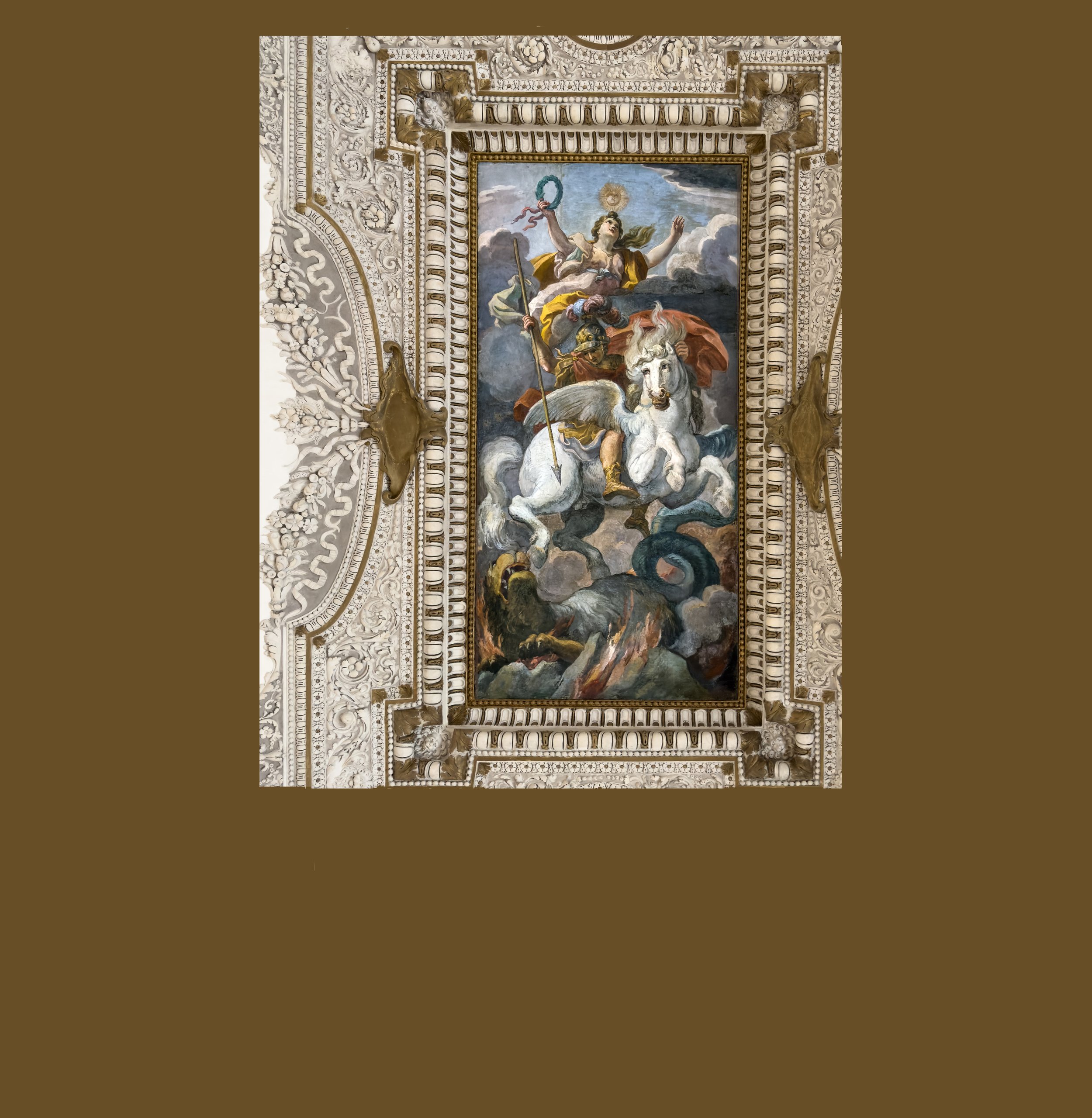

In this image of a mythological figure embodying or foreshadowing a Christian cardinal virtue, Bellerophon represents Justice. In the Iliad, Homer depicted the Chimera with a lion's head, a goat's body, and a serpent's tail: "her breath came out in terrible blasts of burning flame;" it was terrorizing the areas of Caria and Lycia in southwestern Asia Minor. Bellerphon was sent on a mission to kill the Chimera and with the help of Athena, he flew Pegasus into battle. After Bellerophon felt the hot breath of the Chimera, he decided to attach a large block of lead to the tip of his spear and thrust it into the Chimera's throat. The Chimera's fire-breath melted the lead, which blocked its air passage and suffocated it.

Museum label: The third flight of the grand staircase in the Palazzo Barberini ends before a relief of a lion, ideally ushering the visitor into the reception rooms. This Roman era sculpture came from a funerary monument discovered in the vicinity of Tivoli and was worked into the decoration of the staircase both for its imposing nature and for its emblematic and allegorical implications. This, because the lion was not merely a symbol of strength and fortitude, it was also the astrological ascendant of Pope Urban VIll Barberini who was particularly sensitive to astrology.