The Hall’s wall-frescoes depict episodes in the life of the Roman emperor Constantine: The Vision of the Cross, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Baptism of Constantine, and the Donation of Constantine. He was the first emperor to embrace Christianity and to concede freedom of religion within the Empire. The entire Hall is a celebration of the triumph of the Christian religion over paganism. This was the last of Raphael’s Stanze to be decorated. Due to Raphael's death in 1520, at age 37, his assistants finished the frescoes, utilizing Raphael’s preparatory sketches.

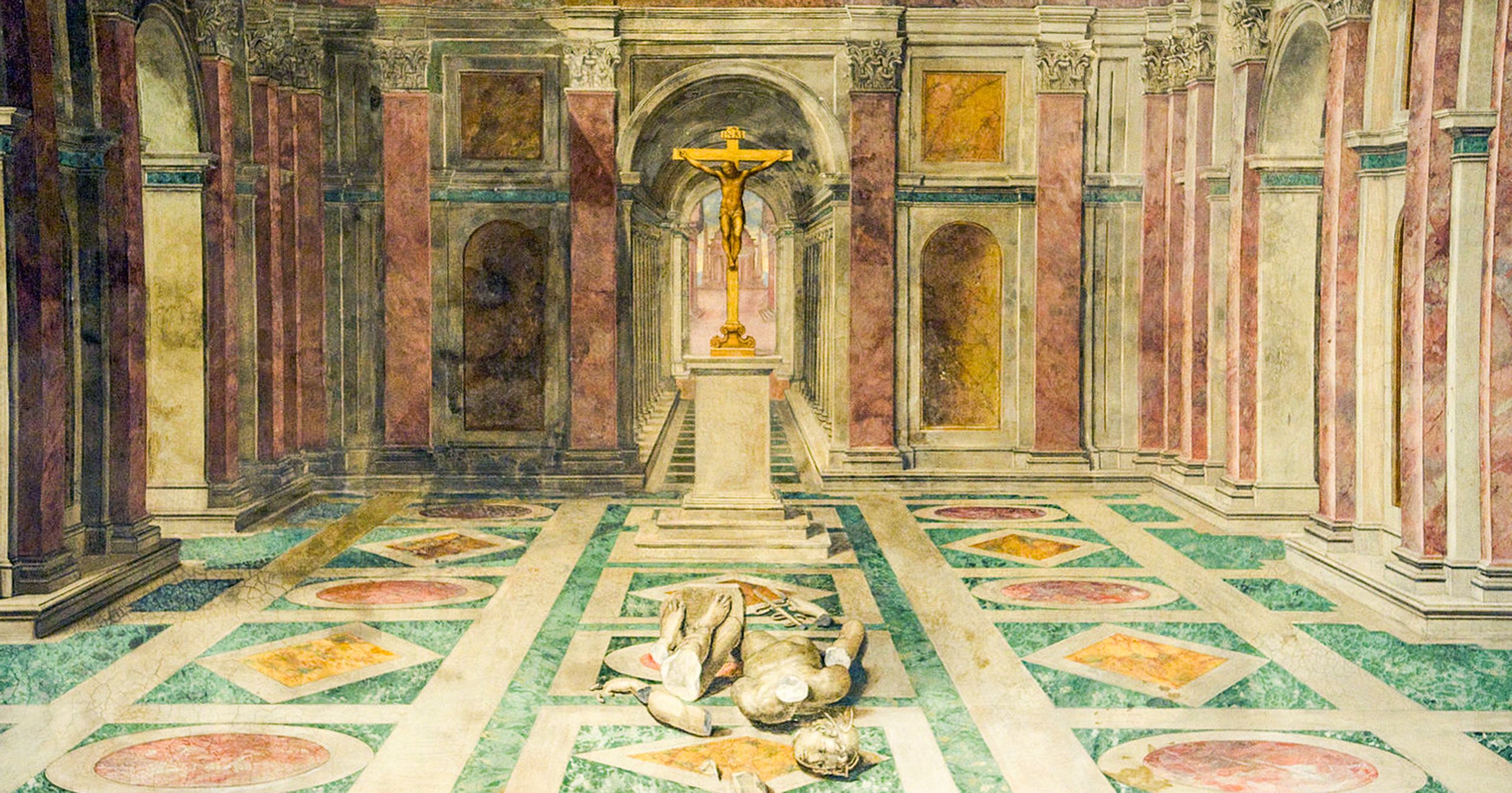

The original wooden roof which Leo X (pontiff 1513 to 1521) had built was replaced under Gregory XIII (pontiff from 1572 to 1585) by the modern ceiling, the decoration of which was entrusted by order of the Pope to Tommaso Laureti who portrayed the Triumph of Christianity in the central panel to express the success of Christianity in honor of the first holy Roman emperor, Constantine. The work was completed under Pope Sixtus V (pontiff 1585 to 1590). The panel is surrounded by paintings of eight regions of Italy and three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa. The corners of the ceiling depict the undertakings of Gregory XIII, and the frieze above shows heraldic elements of Sixtus V.

Within the Triumph of Christianity, Laureti captures an outstanding perspective of depth which pays tribute toConstantine’s destruction of all pagan idols within Rome (although actually Constantine did not destroy the pagan idols). The broken idol on the floor represents the removal of pagan gods/religion, which is replaced by Christ’s image on the cross, thus symbolizing the triumph of the Christian religion.

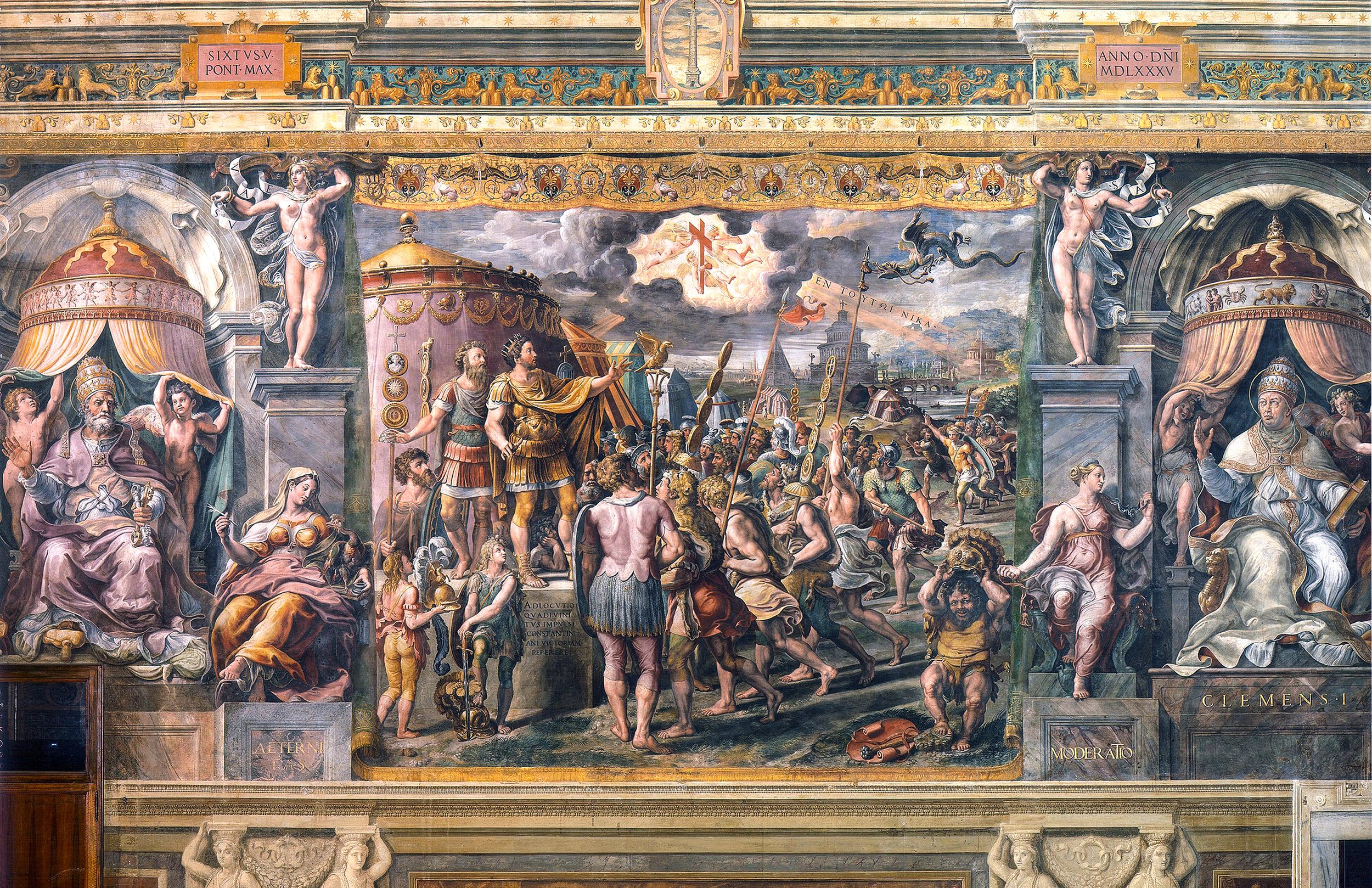

The Vision of the Cross refers to the vision that came to Constantine (272–337 A.D.) just before the bloody battle against Maxentius, who had proclaimed himself to be the emperor of Rome. The Vision of the Cross was a key event that was said to have been a step towards Constantine’s conversion to Christianity during his battles to become emperor. Also, as shown on both sides of the fresco, Vision of the Cross, decoration of the Hall’s walls was completed with figures of great Popes flanked by allegorical figures of Virtue, e.g., as shown here, on the right, is a portrait of Clemens I sitting on a papal throne.

According to the Eusebius' Life of Constantine (337 AD), in which he claimed to have heard the story from Constantine himself, Constantine saw a vision of "a cross-shaped trophy formed from light" above the sun at midday. In The Vision of Constantine, he is depicted in a military camp looking towards a giant cross in the sky that is surrounded by Greek words (τούτῳ νίκα) saying, “In this sign, conquer,” telling him that he would win the battle only if he used that symbol as his standard.

According to Georgio Vasari’s (1511-1574) Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Raphael painted two figures somewhere in the Vatican rooms while experimenting with oil paint. In 2017, restoration artists found that unlike other figures, the figures of Justice and Friendship were painted in oil. Analysis of the brushstrokes confirmed that Raphael was the author of the allegories, created in 1519 shortly before his death in 1520. Raphael’s Friendship, wearing a blue gown, is found in the right corner of The Vision of the Cross.

The first fresco in the Hall of Constantine showed Constantine and his army as they witness the miraculous vision of a cross in the sky. The second shows him aided by angels and defeating Maxentius in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge just outside of Rome. The two murals teach viewers that Constantine won the decisive Battle of the Milvian Bridge because he heeded a heavenly message.

This preparation drawing by Raphael, A Warrior Riding a Horse and Figures of Two Nudes Fighting seems to be reflected in the detail picture below in which a rider on a black horse, behind and to the right of Constantine, is engaged in battle. Raphael used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, apparently to a greater extent than most other painters, to judge by the number of variants that survive: "...This is how Raphael himself, who was so rich in inventiveness, used to work, always coming up with four or six ways to show a narrative, each one different from the rest, and all of them full of grace and well done" wrote another writer after his death.

This detail of The Battle of the Milvius Bridge shows that Constantine (in gold), as instructed in his vision, changed his military standards to bear Christian signs and symbols. e.g., the cross, and, consequently, sword-wielding angels (flying above Constantine) then joined him in the battle. The two frescoes claim both that Constantine chose to fight for God and that God therefore chose to fight for him.

The victory Constantine won with the help of the Christian God placed the emperor — and thereby the empire as well — under the protection of the Cross and in direct dependence upon Christ.

Already known as a skillful general, Constantine first launched his cavalry at the cavalry of Maxentius and broke them. Constantine's infantry then advanced; most of Maxentius's troops fought well but they began to be pushed back toward the Tiber. Maxentius then decided to order a retreat, intending to make another stand at Rome itself. However, there was only one escape route, via the bridge. Constantine's men inflicted heavy losses on the retreating army.

Based on the designs of Raphael, who died in 1520, The Battle of the Milvian Bridge was painted by his assistants, Gianfrancesco Penni, Giulio Romano, and Raffaellino del Colle between 1520-1524 in the Hall of Constantine. Above is Raphael’s drawing in red chalk of a horse and rider that was included in the fresco, as can be seen in the center of the photo below, i.e., the white horse that has fallen onto its belly, with its rider looking up to the sky, perhaps at the flying angels with swords (see full fresco in top picture).

This detail from The Battle of the Milvian Bridge depicts Constantine’s brother-in-law Maxentius (lower right), wearing a crown as the rival imperial claimant, struggling on his horse in the Tiber River. He seems to be looking up at Constantine (see top photo of the fresco) who is carrying a lance and leading the battle of his victorious human and spirit army. This detail image alludes to the report that Constantine’s outnumbered forces defeated Maxentius’ forces, which tried to retreat over the River Tiber on a pontoon bridge. In the chaos of the retreat, the bridge collapsed, leaving only the too-narrow Milvian Bridge as a route to escape. Maxentius and many of his men would drown or be trampled to death in the escape.

Justice (left) is the other figure, besides Friendship, Raphael painted while experimenting with oils in the Hall of Constantine. However, his students didn’t dare finish his experiment with oil and used the secure and reliable fresco method for the Hall, as seen in the portrait of Pope Urban V and the allegory of Charity, both to the right of Justice, as shown above.

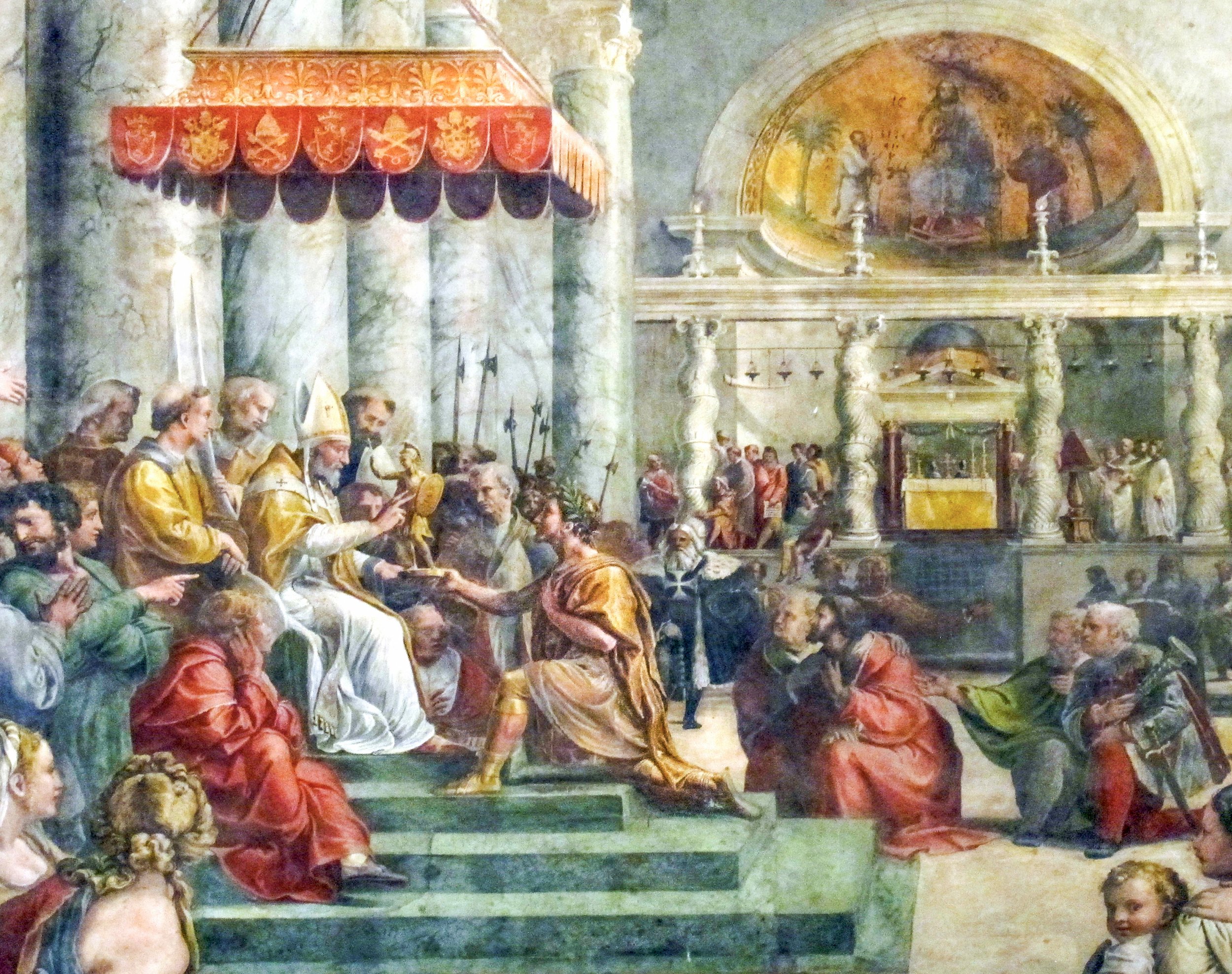

The third fresco, opposite the wall of The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, depicts the legend of the Baptism of Constantine, suggesting what happened after the great victory at Milvian Bridge. The emperor, naked, kneeled before Pope Sylvester who baptized him, thus becoming the defender of Christianity. The figure of Pope Sylvester has the face of Clement VII, in homage to the pontiff who had continued the works in this Hall. In fact, it is widely accepted that Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia baptized Constantine on his death bed, as was the custom of the time.

The baptism depicted here takes place in the Baptistry of the Lateran Basilica, which Constantine erected after his battle with Maxentius on the demolished campsite of his opponent's elite cavalry. Penni depicted the octagonal structure with its mighty Ionic pillars with great fidelity. Constantine kneels before Pope Sylvester I, who pours water over the emperor's head from a dish. Above stands a man dressed in blue holding a long cross that points to the sign of victory sent by God and is the symbol of Constantine's rule.

According to legend, Constantine suffered from leprosy and asked pagan priests for a remedy. The pagans told him to slaughter little children and bathe in their warm blood. Constantine refused to do so, and for his merciful restraint, Saints Peter and Paul appeared to him and told him to seek out Saint Sylvester. He found the saint in hiding because of the persecutions, but Constantine led him into Rome in triumph. Sylvester then cured Constantine’s leprosy by having him do penance and take this baptismal bath.

In the fourth mural Constantine, on his knees, offers Pope Sylvester a golden statuette, symbolizing the city of Rome, and representing an actual document, the Donation of Constantine. The three-page Donation announces that the emperor is conferring vast political and ecclesiastical authority upon the Roman Church. However, in 1440, Lorenzo Valla showed that the Latin used in the Donation of Constantine document was not that of the 4th century, and was a forgery composed probably in the 8th century, used especially in the 13th century, in support of claims of political authority by the papacy.

The Donation document authorizes the pope to rule over “the city of Rome, and all the provinces, places, and cities of Italy and the Western regions.” It promotes the pope to be the ruler of the western half of the Roman Empire. As the Donation puts it, “Where the supremacy of priests and the head of the Christian religion have been established by the heavenly Emperor, it is not right that there an earthly emperor should have jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Donation proposes the pope’s religious and political authority comes directly from God. Priestly and papal rule trumps mere political rule and is sufficient to replace it. Only in 1870, when the popes lost the last remnant of their political authority, did the Church cease to be directly involved in political rule.

After enjoying the artistic genius of Raphael in the four stanze in the Papal Palace, Vatican City, The Room of the Signature, The Room of Heliodorus, The Room of the Fire in the Borgo, and The Hall of Constantine, I thought it important to present a portrait of the artist as a young man.