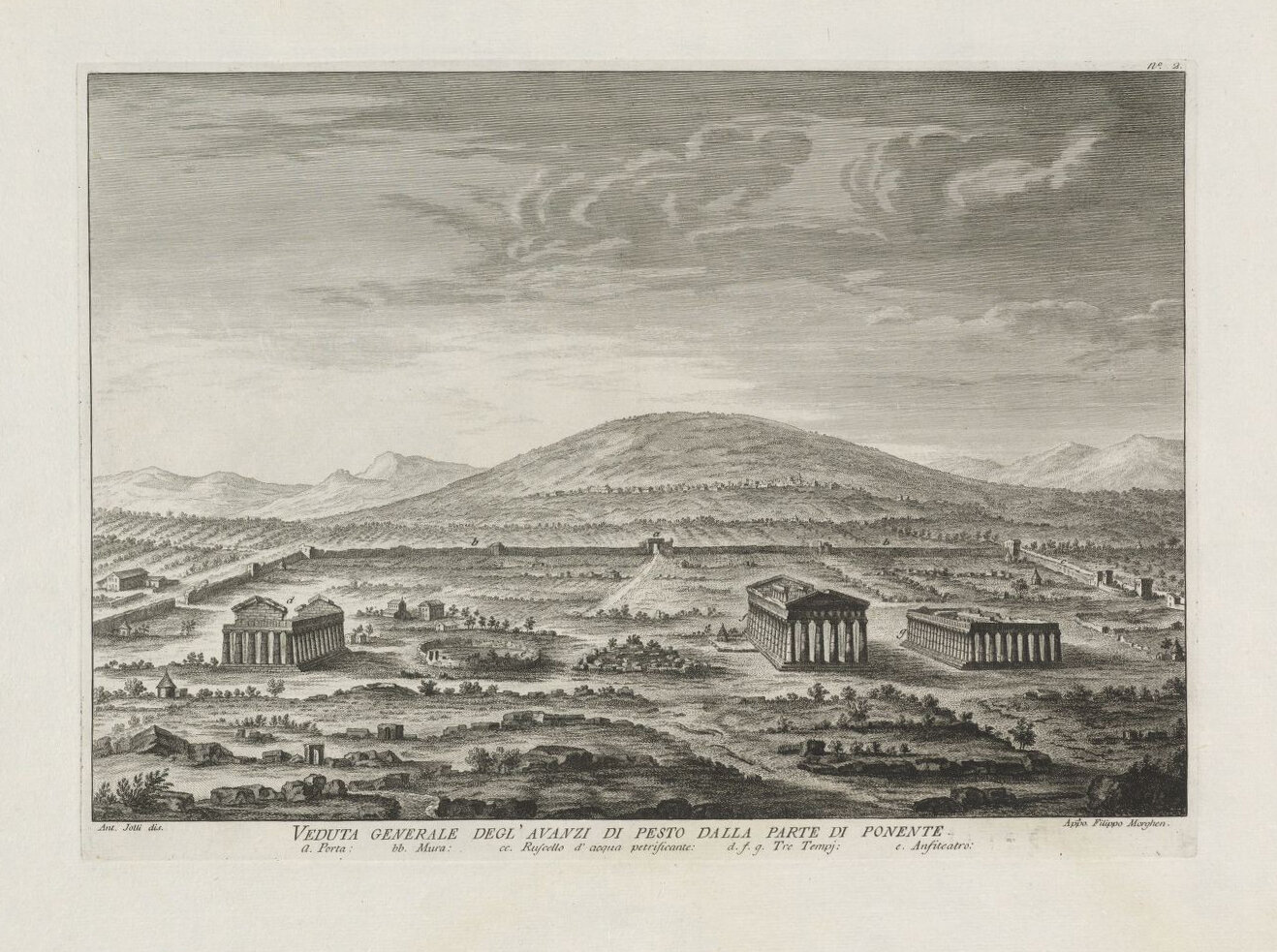

One of Filippo Morghen etched plates showing a view of Paestum with its three Greek temples as seen by him in the mid-18th century. However, long before the Greek diaspora made its way to the site where Paestum stands it had been inhabited ever since the Middle Paleolithic, a prehistoric period spanning from 135,000 to 35,000 years ago.

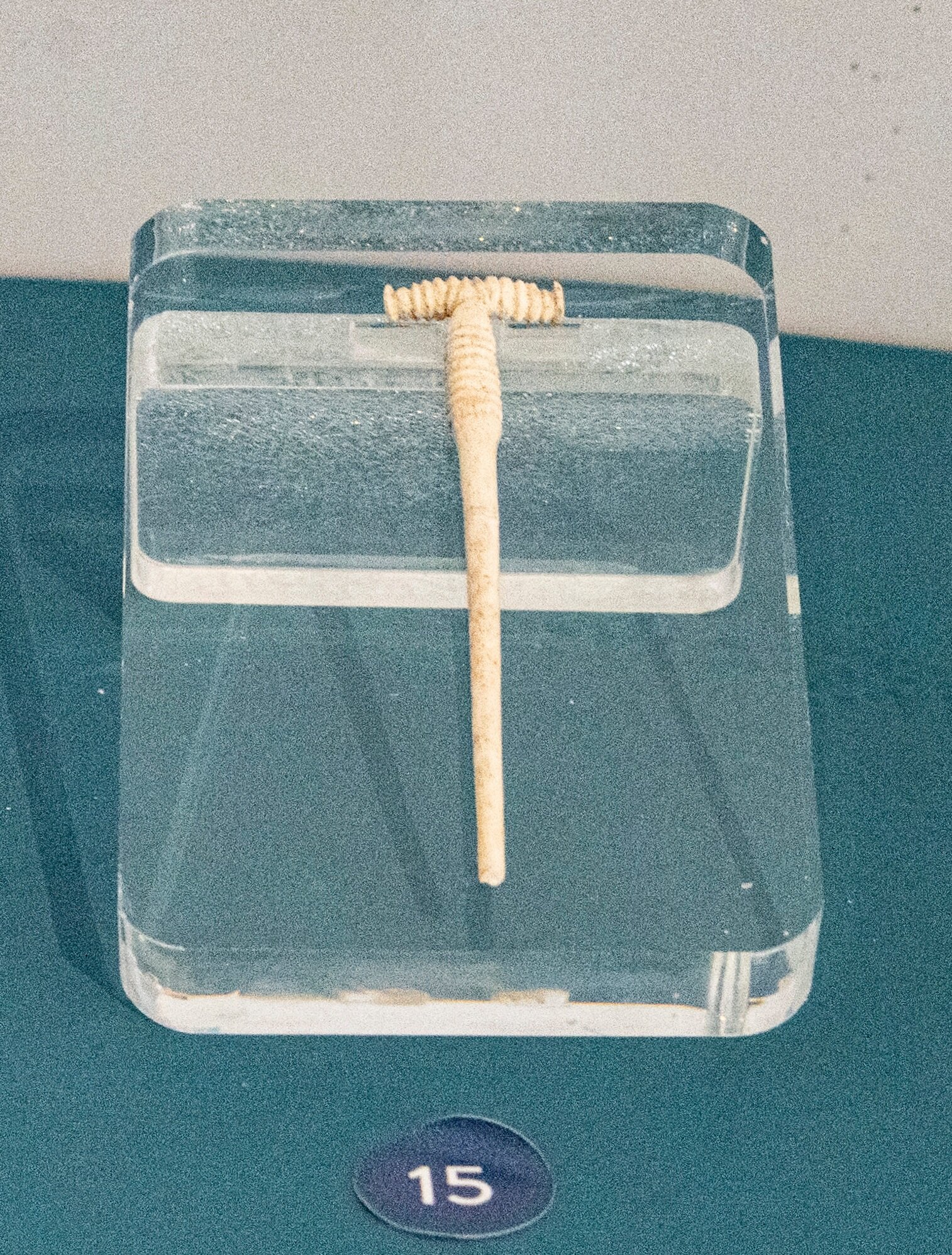

During the Paleolithic era (Old Stone-Age) human beings were still not anatomically modern at this time. In the Paleolithic era, there were more than one human species but only one survived until the Neolithic era. They lived on hunting and gathering, adapting to the local environment, as indicated by the discovery of typical flint tools (blades and scrapers), such as the one shown here.

These stone axes were made during the Neolithic period (roughly 8,000 B.C. to 3,000 B.C.), when ancient humans switched from hunter/gatherer mode to agriculture and food production. They domesticated animals and cultivated cereal grains. They used polished hand axes, adzes for ploughing and tilling the land and started to settle in the plains. Advancements were made not only in tools but also in farming, home construction and art, including pottery, sewing and weaving.

Ranging in size from as small as a guitar pick to a length of several inches, Stone Age knives were usually flakes of flint, quartz or obsidian. Small and typically rounded, knives used for slicing through animal flesh had a cutting edge and a thick blunt side for holding. Scrapers were used for cleaning animal skins in the process of making leather. Burins were used for carving or engraving wood and bone, like a chisel. Blades were used as knives and microliths were tiny flints that were glued/fixed to wooden shafts to make arrows or spears for hunting.

Obsidian rock was used by early human civilizations to create tools such as arrowheads, blades, and other sharp objects. Obsidian igneous rock occurs as a natural glass formed by the rapid cooling of viscous lava from volcanoes.

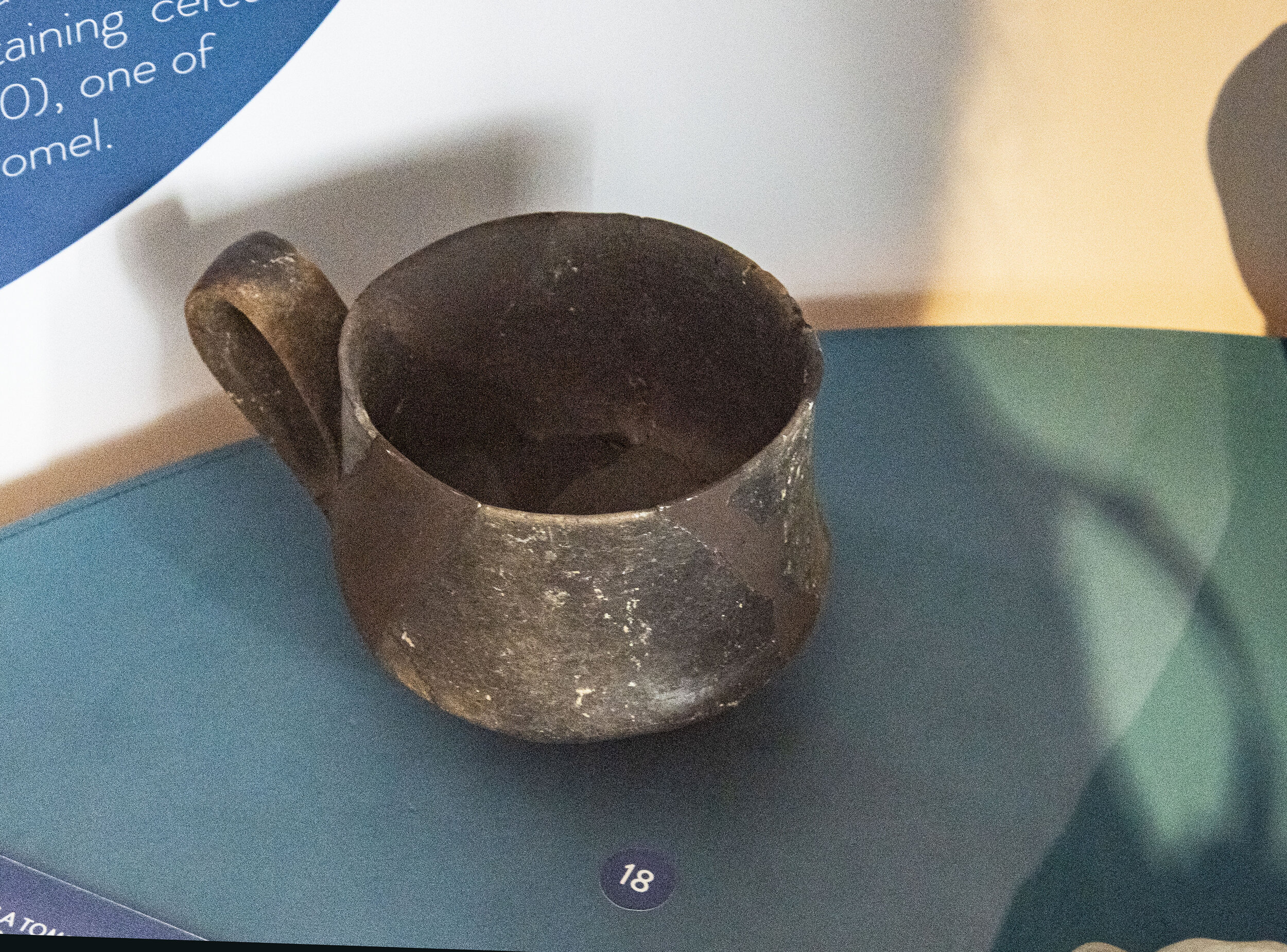

A pyxis is a shape of vessel from the classical world, usually a cylindrical box with a separate lid. Originally mostly used by women to hold cosmetics, trinkets or jewelery, surviving pyxides are mostly Greek pottery, but especially in later periods may be in wood, metal, ivory, or other materials.

Ladle on the right (#17) and flask in on the left (19).

The Gaudo people would apparently use tombs repeatedly, perhaps for different generations of people. It has been seen that the body of the most recently deceased would always be placed at the back of his burial chamber, with the previous tenants of that chamber placed beside him. Study of the arrangement of bones and accompanying artifacts has led researchers to believe that the Gaudo society was structured into different family groups or warrior clans of some kind.

Some of the oldest colonies in southern Italy, known by the Greeks as “Magna Graecia,” include Cumae, Taranto, Sybaris and Reggio Calabria. Beginning in the 8th century BC, Greece witnessed a period of mass emigration that led to the founding of numerous Greek communities, known as “colonies,” in other parts of the Mediterranean and on the Black Sea coast. As it is in todayʻs world, economic problems and political struggles were the main factors that led many people to leave their homeland and set off on a dangerous journey to other lands.

The temples, the oldest to be found on Italian soil, were very different from Roman classical. We now know that what the 18th-century visitors called the Temple of Neptune (now named Temple of Hera II and dated c. 460 BC), the Temple of Ceres (Temple of Athena, c. 520 BC), and the Basilica (Temple of Hera I, c. 530 BC) were the creations of Greek colonists who had founded Poseidonia in 600 BC (the city was renamed Paestum after the Roman conquest of 273 BC).

The original founders surrounded Posidonia/Paestum with walls, (on average 5 m in thickness and about 7 m in height). According to Strabo - the father of western geography - the Greek city was founded as Poseidonia by Achaen colonists in 600 BC fleeing from Sybaris, which had been founded ca. 720 BC when the people of Achaea and Troezen, a region and city respectively, emigrated from the Peloponnese.

There were 4 main access doors, (Porta Marina, Porta Aurea, Porta Sirena, Porta Giustizia). The Porta Sirena is at the center of the eastern side of the Paestum city walls.

Of the three temples, the Temple of Athena (far right) is the best preserved. The area on the northern edge of the settlement was dedicated to Athena, and the area to the south, which contains the Temple of Hera I (left) and the Temple of Hera II (middle), was dedicated to the goddess Hera. The main task of the Greek architect was to design temples honoring one or more Greek deities. The temple was merely a house (oikos) for the god, who was represented there by her/his cult statue.

There are no temples or sacred areas dedicated to Poseidon in the Paestum area. The only traces of Poseidon are found in the name of the city, on its coins, and on this Attic vase. The Attic vase, red-figure technique, used here, was an Athenian invention of the late 6th century BC and is one of the most important styles of figural Greek vase painting. Although vase production in Athens stopped around 330–320 BC., it continued in the 4th and 3rd centuries in the Greek colonies of southern Italy where five regional styles may be distinguished, i.e., Apulian, Lucanian, Sicilian, Campanian and Paestan.

In the northern sacred area was found horse figurines, which evoke the world of Poseidon, god of the sea and lord of horses.

Nomos (money) of Poseidonia, c. 530–500 BC. Poseidon is seen wielding a trident with a chlamys draped over his arms. The coins of Paestum begin about 550 BC. These early issues were perhaps all festival coins. They usually have Poseidon with upraised trident. Issues continue until the reign of Tiberius (14-37 CE).

The first temple that one sees on entering the site is the ancient Greek Temple of Athena. Built in the 6th century BC, the temple was thought to have been attributed to Ceres, the goddess of corn, or of harvest, though recovery of several terracotta statuettes of Athena confirms that it is consecrated to this deity, who was the goddess of wisdom and virtue.

In the northern sacred area of Paestum, many terracotta figurines of the goddess Athena were found, as well as vases depicting Athena In addition, statues of Athena that graced Roman houses were found.

Many miniature vases were found in this sacred area, mostly hydriskai, possibly vestiges of rites connected to water.

Goddess Athena was the mythological goddess of wisdom, but also the poetic symbol of reason and purity. Goddess Athena was very important to the Greeks, since they named her the Iliad's goddess of fight, the warrior-defender, the protector of civilized life and artisan activities.

Attic red-figure vases were exported throughout Greece and beyond. For a long time, they dominated the market for fine ceramics. Only few centers of pottery production could compete with Athens in terms of innovation, quality and production capacity. Of the red figure vases produced in Athens alone, more than 40,000 specimens and fragments survive today. From the second most important production centre, Southern Italy, more than 20,000 vases and fragments are preserved.

The Temple of Athena has a simpler structural design as compared to the other two temples. Note that the columns are all slightly curved in at the top. They are in fact slightly cigar shaped. This was a feature of the earliest temples intended to cause an optical illusion.

The ancient Greek temples were meant to serve as homes for the individual God or Goddess. In exchange, the Greeks were expecting the Gods to protect them and sustain their communities. Athena, also known as Athene, is the Goddess of Wisdom (also Goddess of courage, inspiration, civilization, law and justice, strategic warfare, mathematics, strength, strategy, the arts, crafts and skill).

Statuette of Athena. Pentelic marble (from Mount Pentelicus). This statuette copies the Athena Parthenos by Pheidias. Although unfinished, the work is important because it preserves the relief representation of an Amazon battle (mythical battles between the ancient Greeks and the Amazons, a nation of all-female warriors) on the exterior of the shield and the relief image of the Birth of Pandora on the base — themes that adorned the original statue of Athena.

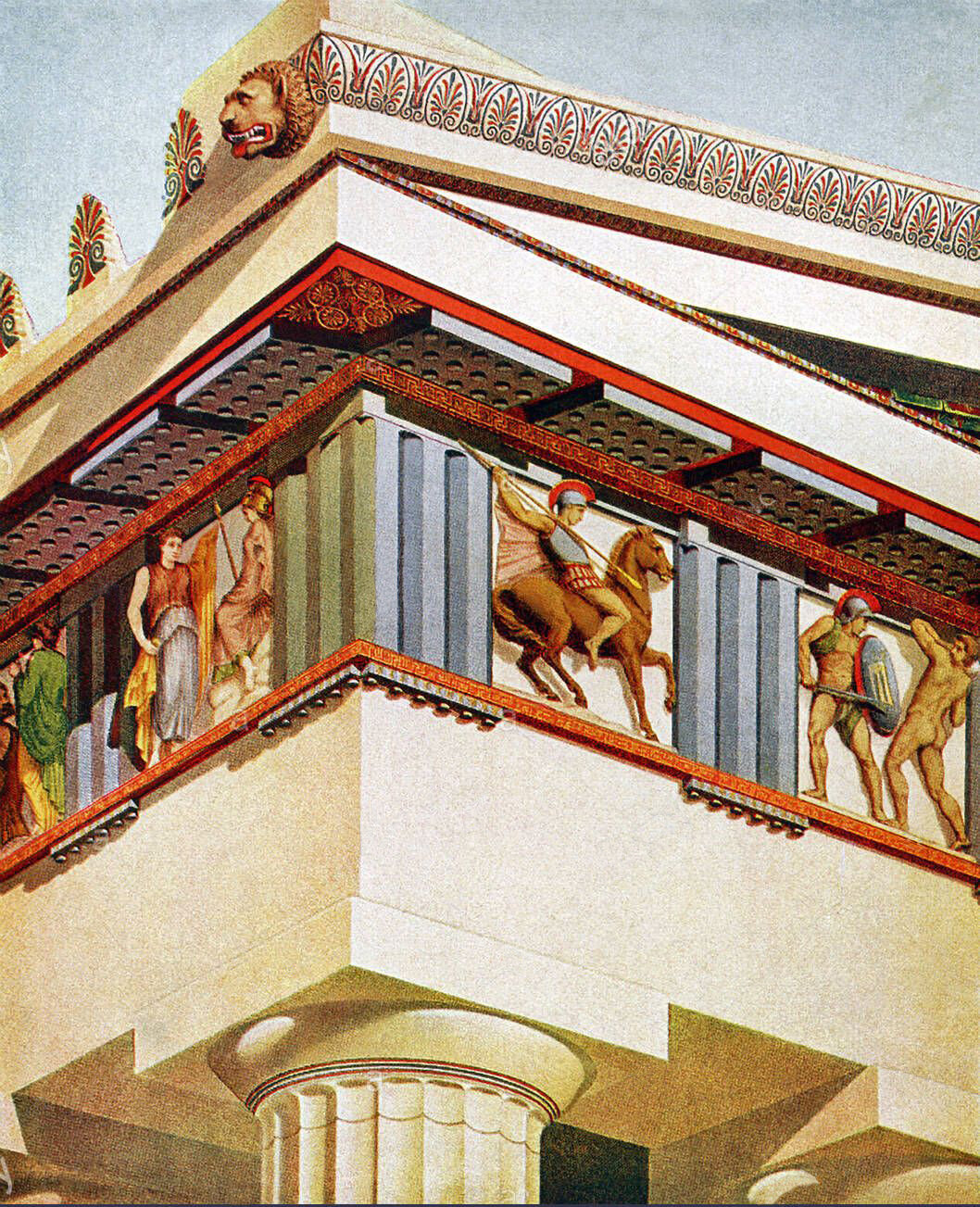

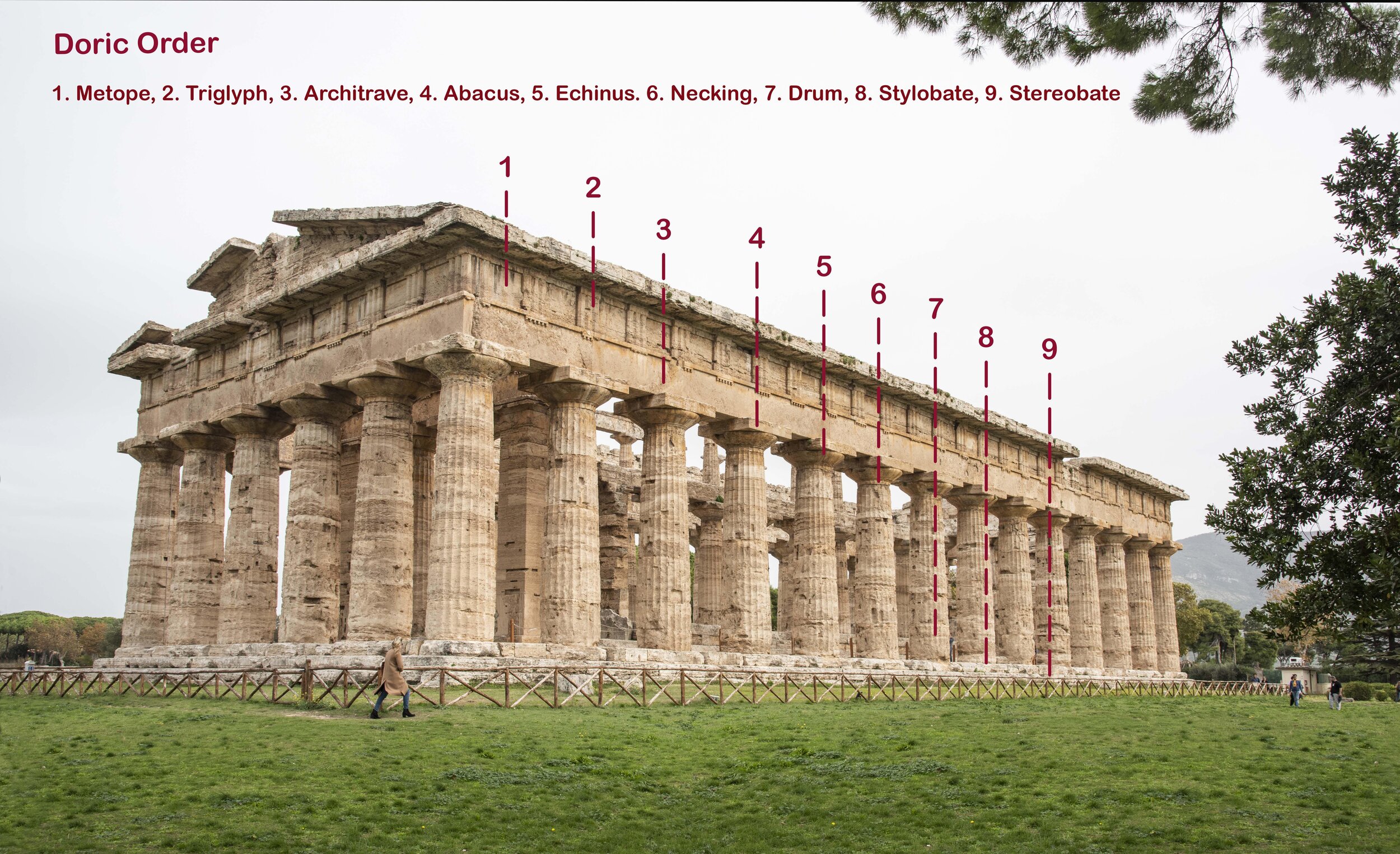

The far (western) end of the Temple of Athena. The entablature here is rather better preserved and it is possible to see the line of the metopes and the trigyphs where the main painted decoration would have been. A trygyph is a tablet in a Doric frieze with three vertical grooves. Triglyphs alternate with metopes.

Triglyph is an architectural term for the vertically channeled tablets of the Doric frieze in classical architecture, so called because of the angular channels in them. The rectangular recessed spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze are called metopes

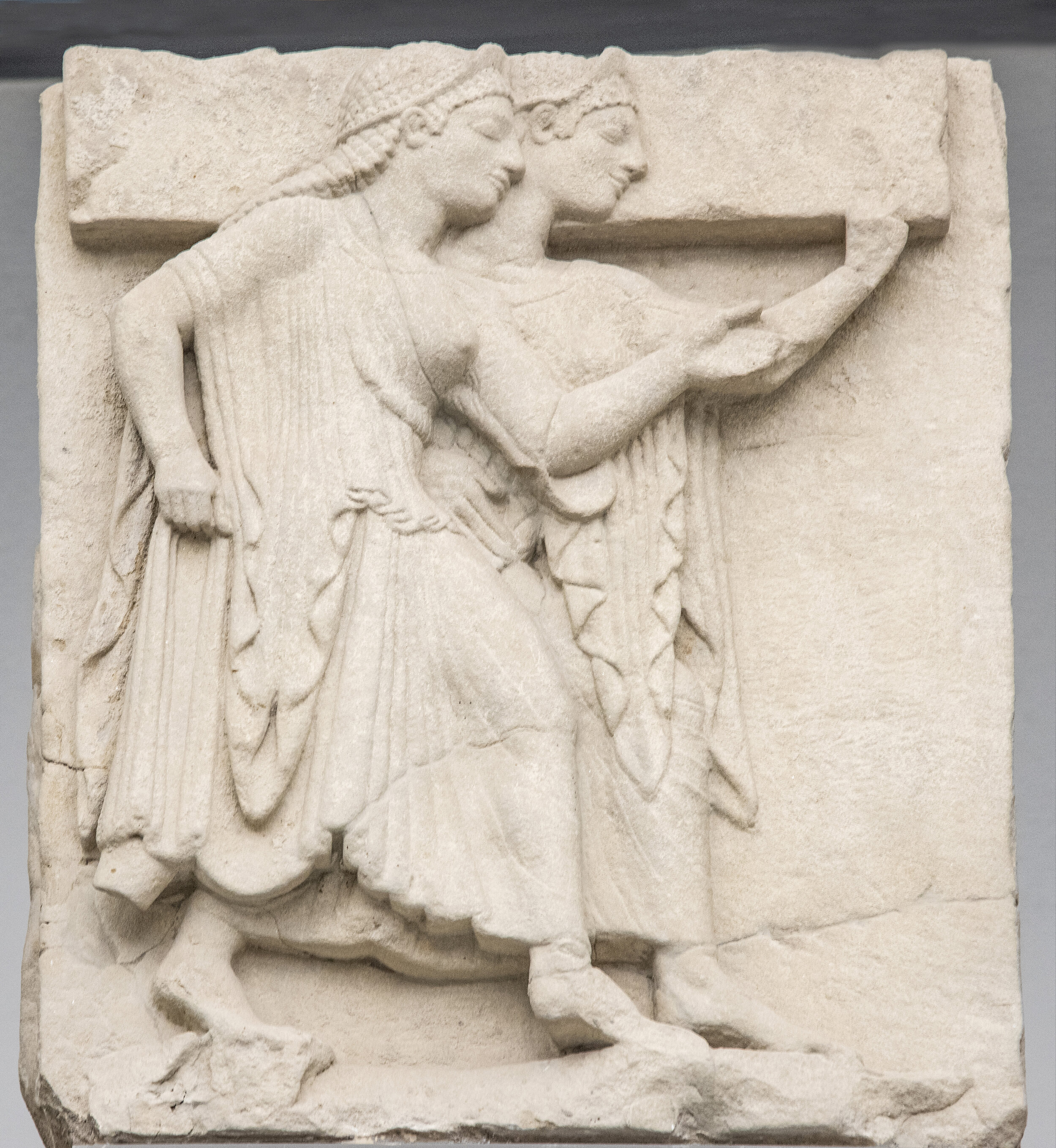

This metope was found at the Sanctuary of Hera at the mouth of the Sele River. The archaic metope relief panels date from 570-560 BC. The earliest group of metopes shows the story of the life of Heracles in 38 surviving reliefs. This metope illustrates the story when Heracles shot Alcyoneus with an arrow, Alcyoneus fell to the ground but then began to revive, so on the advice of Athena, Heracles dragged Alcyoneus out of his homeland where Alcyoneus then died.

Ajax was considered the second-best hero at Troy, after his cousin Achilles. Once Achilles dies, Ajax and Odysseus debate over who should receive his armor. When Odysseus is given the armor, Ajax goes mad. He kills Greek cattle believing that it is the Greeks. Once he becomes aware of what he has done, he commits suicide. Ajax believes that after the cattle incident, killing himself is the only way to keep his status as a hero and to avoid bringing shame to his noble father, Telamon.

This metope is about Apollo and Artemis who killed most (or all) of Niobe's children, leaving Niobe to weep eternally. Artemis and Apollo remained close to each other forever. Both siblings would become associated with the skill of archery, and they enjoyed hunting together. In addition, both had the power to send plagues upon mortals.

In front of the temple was the altar where the sacrifices took place. Greek temples differ from Christian churches in that whereas in a church the ceremonies are all enclosed and took place within the church, the Greek temple was essentially a store house where the statues of the gods were preserved to be brought outside for ceremonies.

Students sit on the altar located in front of the Temple of Athens, which is where the sacrifices took place. The main rituals took place outside in the altar in front of the Temple, e.g., the sacrificing of animals. This was always a time of rejoicing, for after the sacrifice took place the animals were roasted, and the gods enjoyed the smell of the roasting and had received a token offering of the meat; the meat was then cut up and distributed among the worshipers, who then had a good feast.

In ancient Greece, animal sacrifice was a practice that honored the gods and brought people together through sharing of meat. It was widespread at the level of the state, which organized large sacrifices during important festivals and distributed the meat to the people, as well as in private life. Attic vase painters often depicted various aspects of the sacrificial process, such as the procession to the altar, the butchering of the animal (as depicted here), the burning of the part offered to the gods on the altar, and the feasting during which the animal was consumed.

The Graeco-Lucanian inhabitants of Poseidonia allied themselves with Pyrrhus of Epirus when he arrived in Italy in 281 BC to lend aid to Tarantum (Taras) against the Romans. The Romans nevertheless managed to conquer much of the Italian peninsula by 272 BC. Poseidonia was refounded as the Roman city of Paestum. In this form, the city managed to grow and flourish until the fourth century AD, after which it slowly declined. It was abandoned by the seventh century.

The Ekkelesiaterion was part of the agora, a public space and meeting area in ancient Greek cities. Its steps, made from the natural outcrop of rock, form a circular structure with concentric rings. The Paestum Ekklestasterion was built by the inhabitants of Poseidonia (circa 480-470 B.C.) for meeting of the assembly of citizens who voted for the laws and elected the magistrates; it could seat from 1100 to 1700 people.

The heroon of Paestum is thought to have been erected as a cenotaph (a monument to someone buried somewhere else) to celebrate Is, the mythical founder of Sybaris after the Sybarites moved to the region. The shrine was constructed underground. After excavations during the 1950s, the tumulus ( an ancient burial mound) above the heroon was removed and now the roof can be seen sticking out of the ground. The rest remains buried. Inside the heroon, there is a low stone chamber with a pitched roof. Many objects were discovered inside such as Greek pottery and bronze vessels that contained traces of honey.

A wall enclosed this large rectangular pool. Recent studies have identified the structure as the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, a deity from the Roman Pantheon who was associated with Venus.

The sanctuary, dedicated to Fortuna Virilis, was destined for fertility rites held during the festivals in honor of Venus (Venerea). The sanctuary is associated with a large swimming pool (47 mx 21 m.), the central element of the venerea. On the stone pillars, still visible today, was placed a wooden platform on which was placed the statue of Venus sitting on a throne. Venus is the name for the Roman goddess of love and peace. To the Greeks this was Aphrodite, to the Egyptians the goddess Isis and to the Phoenicians the goddess Astrate.

In general, Aphrodite (Venus) was the captivating goddess of beauty, love, and marriage and her power was very great. Her universality led to a gamut of conceptions of this goddess, who presided over everything from hallowed married love to temple prostitution. Depictions of her in art, literature, and music reflect not only the duality but also the multiplicity of her nature.

The married women who participated in the fertility ritual for Venus immersed themselves in the pool in the hope of having a happy birth. With the demise of the cult of Fortuna Virilis during the Imperial Age (27 B.C. to A.D. 476), the pool was filled in and a new building surrounded by a portico was built over it that was devoted to the Imperial cult through which emperors were worshipped as demigods or deities.

.

The theme of Venus (Aphrodite) associated with fertility is exemplified in this depiction of the myth of Anchises and Aphrodite. The Trojan shepherd Anchises gazes at the seated Aphrodite, his one night on Mount Ida. She holds a small Eros on her lap: this is an erotic encounter. The head of Selene (Moon) appears above the mountain rocks: she indicates night-time. It was from this union that Aineas was born (Museum of Aphrodisias, in modern-day Turkey).

Popular assemblies were held in the comitium and local magistrates were elected. The building of the 3rd century BC lost its role in the 2nd century BC for the benefit of the nearby forum and was partly absorbed by the Temple of Mens Bona.

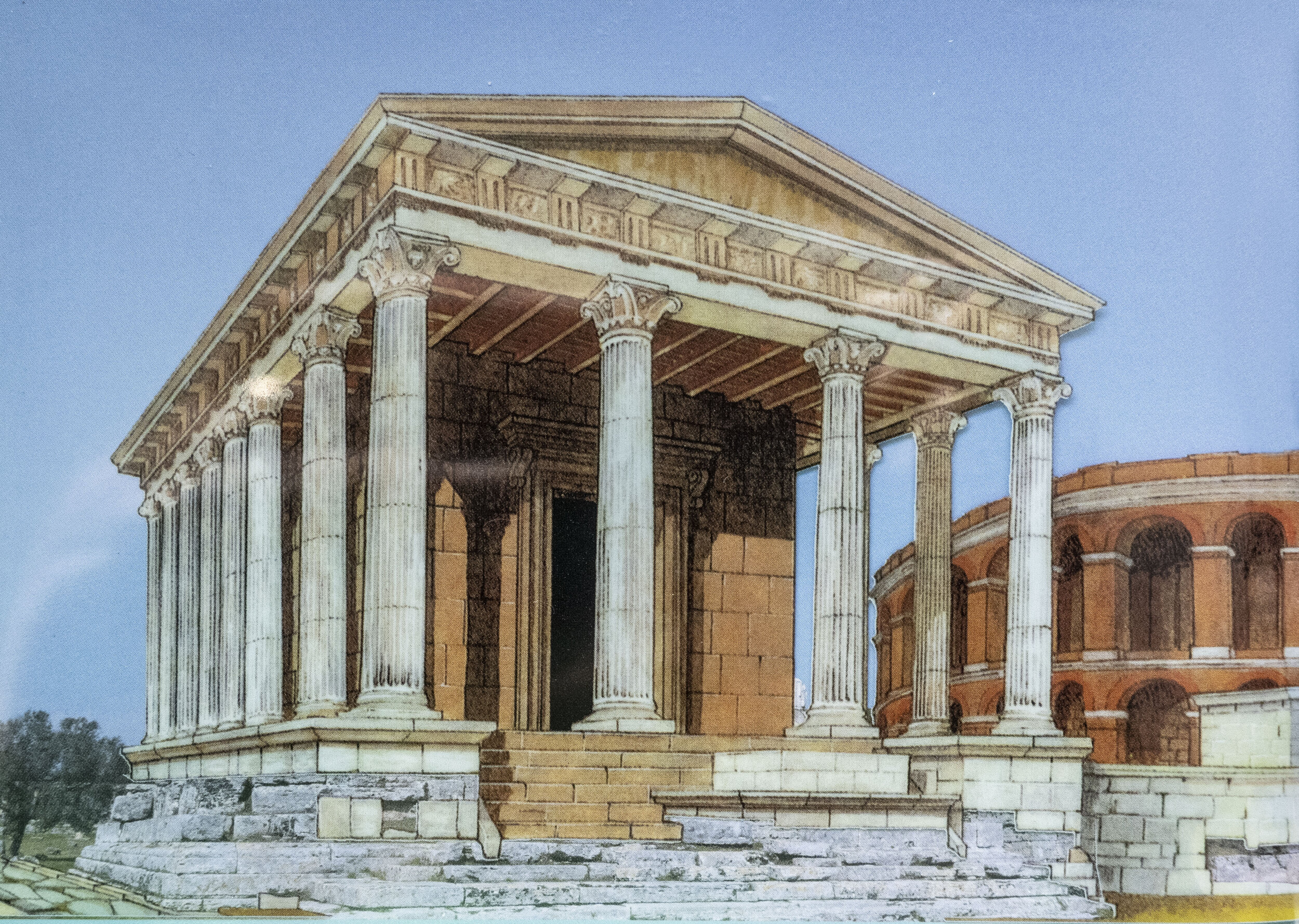

The Temple of Peace with its Corinthian Doric architecture (2nd to 1st century BC) was built in the northern side of the forum. Dedicated to Mens Bona (the Roman deity of reason, a deity that embodied the debt of gratitude of the former slaves to their former masters and in this case the inhabitants of Paestum towards Rome.)

The “Temple of Peace” is also identified as the cityʻs Capitolium. The Capitolium stood opposite the Curia on the other side of the Forum. It was the temple symbolizing the link between Rome and Paestum. Temples of this type were built in the Ist/2nd century AD in many parts of the Roman Empire; they were usually dedicated to the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva). Ceremonies at this temple were mainly related to events of the history of Rome or of the life of its emperors.

"Capitoline Triad" are Jupiter (Zeus), the king of the gods; Juno (Hera), his wife and sister; and Jupiter's daughter Minerva (Athena), the goddess of wisdom. This grouping of a male god and two goddesses was highly unusual in ancient Indo-European religions, and is almost certainly derived from the Etruscan trio of Tinia, the supreme deity, Uni, his wife, and Minerva, their daughter and the goddess of wisdom.

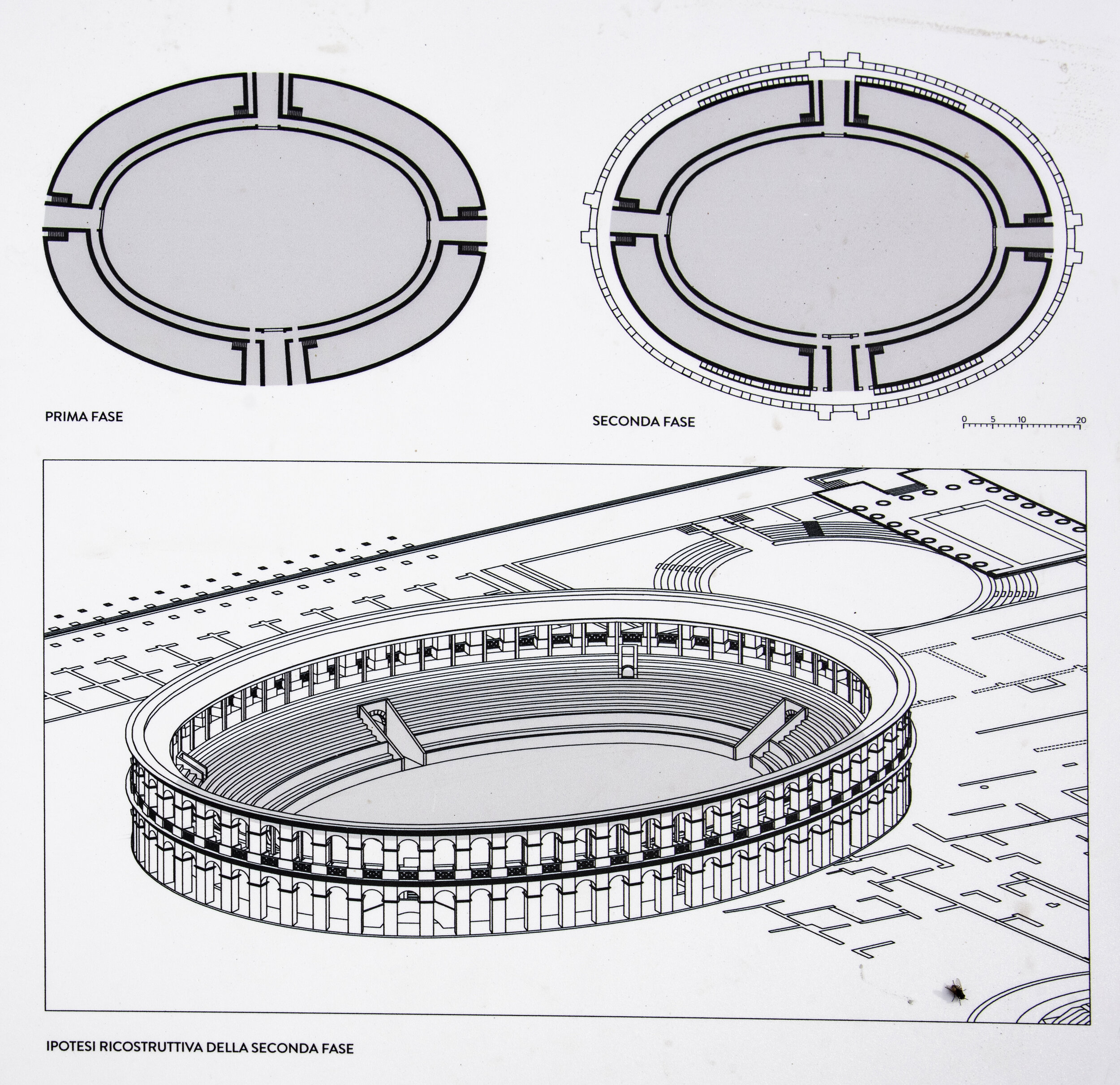

A central element of the Roman Paestum, the amphitheater was built in the Imperial Period (27 BC to AD 476) around 50 BC, and is one of the oldest constructions of its kind. Towards the end of the first century AD an outer ring was added to increase its capacity. Only about a third of the amphitheater is visible today, since most of it still lies buried beneath the present-day road.

In Roman times the cavea (Latin for "enclosure") referred to the seating sections of Roman theaters and amphitheaters. The cavea is traditionally organized in three horizontal sections, corresponding to the social class of the spectators: the ima cavea (in blue) is the lowest part of the cavea and the one directly surrounding the arena. It was usually reserved for the upper echelons of society; the media cavea (in red) directly follows the ima cavea and was open to the general public, though mostly reserved for men; the summa cavea (in yellow) is the highest section and was usually open to women and children.

Only a few of the amphitheaterʻs cavea seats still exist. A high parapet (protective wall) separated the arena from the cavea and was designed to protect the spectators from the animals in the arena. At the end of the first century AD, an outer ring consisting of an arcade resting on pillars was added, a structure, possibly made of wood, formed the upper floor of the cavea (maenianum summum).

The load bearing walls of the amphitheatre and the cavea belong to the oldest phase of its building and were made of large blocks of limestone. The pilasters, supports and arches were built of brick. The arena, like other similar buildings, was used for circus shows and gladiatorial displays. The tunnel that led to the amphitheatre is still intact and accessible and would have been used fro transporting animals, props and sets for the shows.

This building played a vital role in the life of all important Roman cities. In the amphitheaters, the munera gladiatoria ( a gladiatorial contest) were often sponsored by wealthy people who put on public shows at their own expense to celebrate special events or festivals.

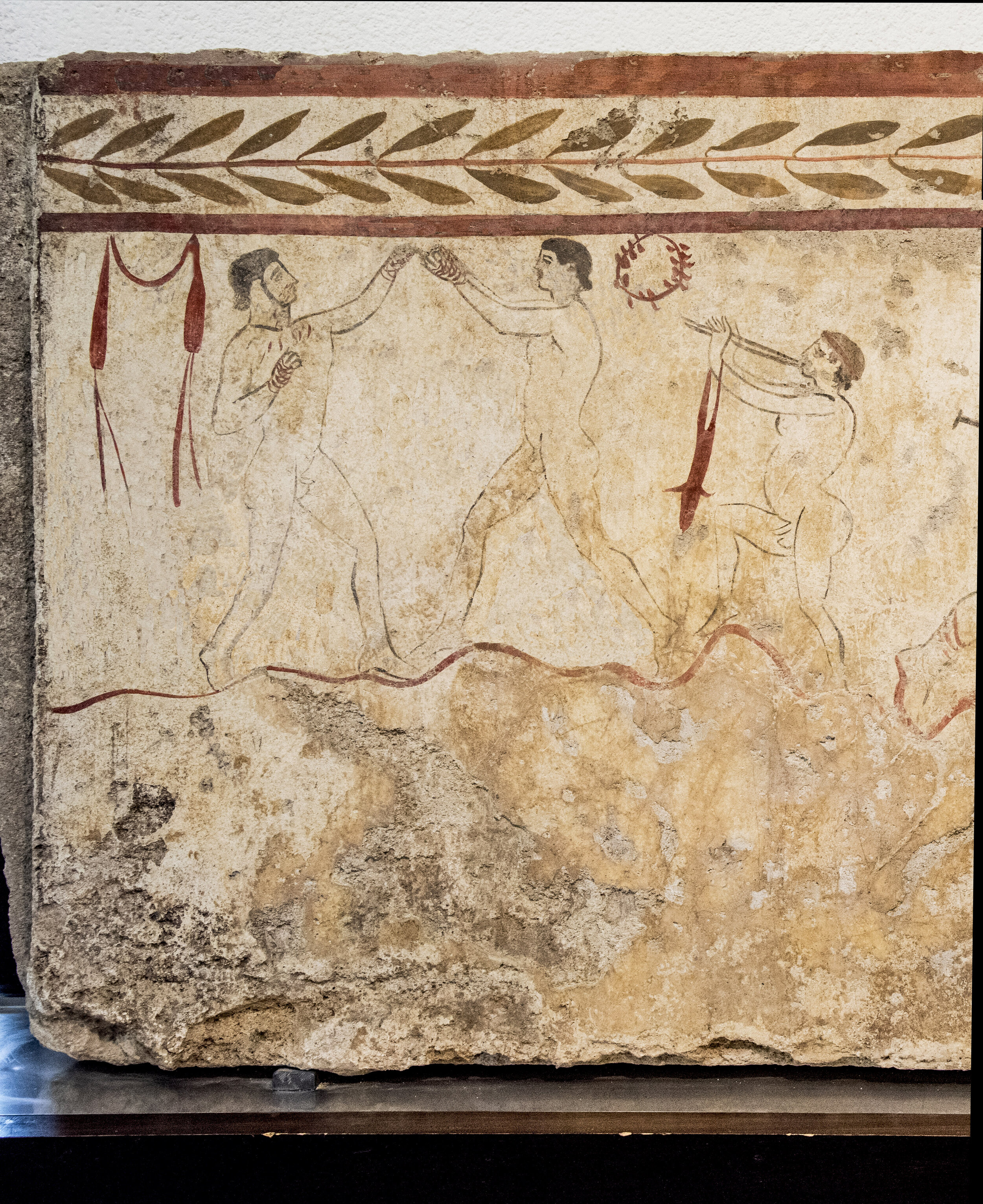

In contrast to the Roman theater, which evolved from Greek models, the amphitheater had no architectural precedent in the Greek world. Likewise, the spectacles that took place in the amphitheater—gladiatorial combats and venationes (slaughter of animals by trained hunters)—were Italic, not Greek, in origin. The earliest secure evidence for gladiatorial contests comes from the painted decoration of a fourth-century B.C. tomb at Paestum in southern Italy.

At the end of the fifth century BC Poseidonia was conquered by the Lucanians. From the archaeological evidence it appears that the two cultures, Greek and Oscan, were able to thrive alongside one another. Many tomb paintings show horses and horse-racing, a passion of the Lucanian elites. Throughout the imperial period, the gladiator combats remained an important route to popular favor for emperors and provincial leaders.

A gladiator (Latin: gladiator, "swordsman", from gladius, "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals.

Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death. In 325 A.D., Constantine, the first Christian emperor, prohibited gladiatorial combat on the grounds that it was too bloodthirsty for peacetime.

Boxing (pugilatus) was a popular sport in ancient Rome. In order to protect the hands from damage, fists were wrapped with leather thongs. With time, the harder skin was used, which increased the strength of the blow and caused more damage. If fighters were feeling even more dangerous, they could box with a cestus. The cestus was a boxing glove, that was essentially a brass knuckle loading with nails and iron. These "gloves" lead to more deaths and more limbs being broken. Boxing fights were banned in 393 CE because of too much brutality.

The gladiator games lasted for nearly a thousand years, reaching their peak between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD. The games finally declined during the early 5th century after the adoption of Christianity as state church of the Roman Empire in 380, although beast hunts (venationes) continued into the 6th century.

In 273 BC, Paestum became a Roman colony. New colonists moved in and soon began to reorganize the town they had taken over. The major change was to abandon the old meeting place, the agora, and establish a new forum a short distance to the south, and this new forum is the major feature of the Roman town. Later the forum was smartened up by the addition of a colonnade running all round, which made it look like a proper forum.

The Forum was surrounded on all sides by small shops, two roomed affairs with a shop at the front and the living quarters behind. The city developed in the mid 6th century BC with paved streets, new houses, sewers and drainage systems which mark out the urban area.

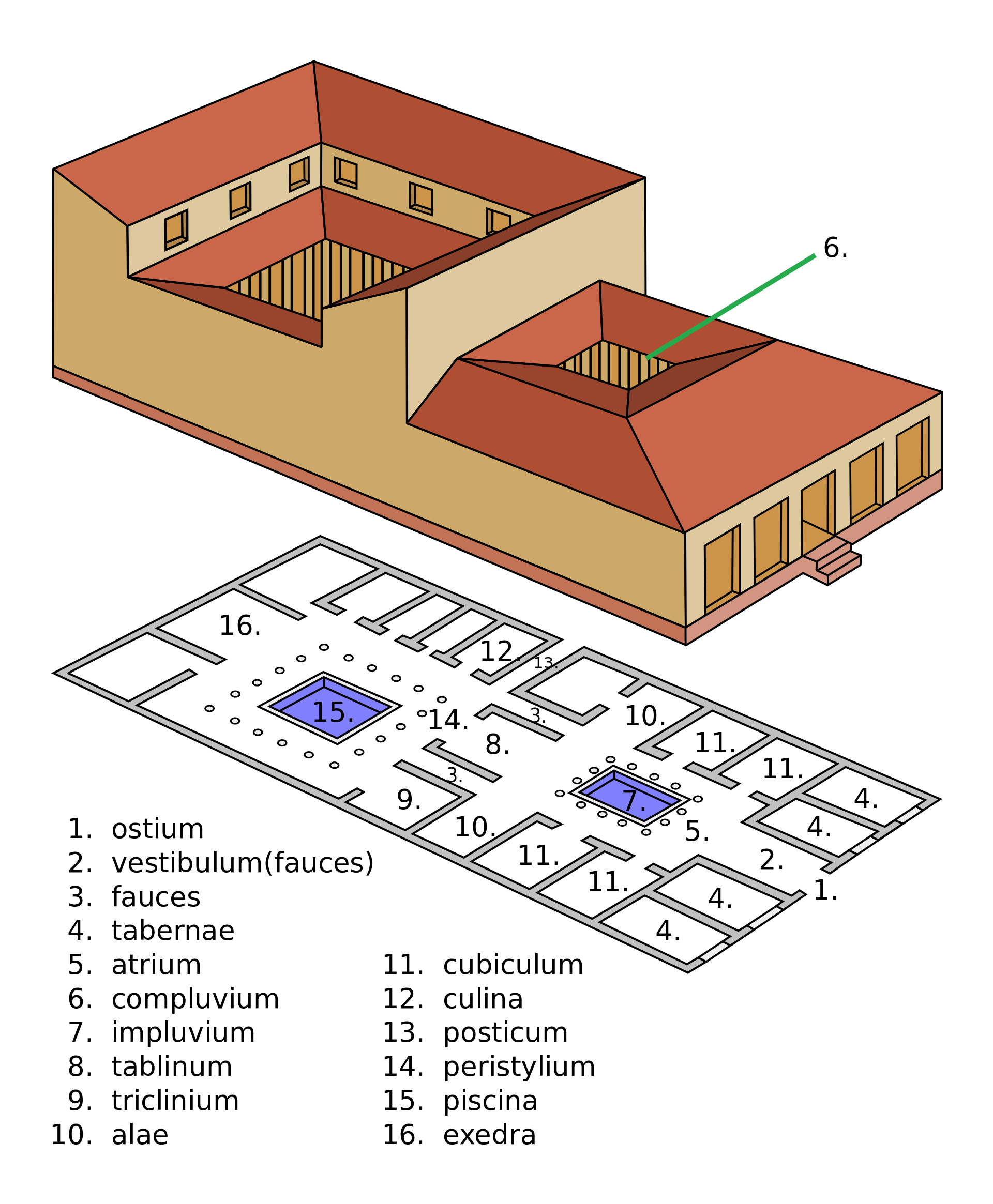

Currently, eight neighborhoods of houses from the Roman period have been unearthed. The dimensions vary a lot and we can find both rich but small houses such as the "Casa con impluvio in marmo" (House with impluvium, 650 sqm) and huge domus like the "Casa con piscina" (House with swimming pool, 2800 sqm).

Houses of the rich and upper classes were lavish. The atrium was the most important part of the house. It was where guests were greeted. The atrium was open in the centre, surrounded at least in part by porticoes with high ceilings, that often contained only a little furniture to give the effect of a large space. In the centre was a square roof opening in which rainwater could come, draining inwards from the slanted tiled roof into the impluvium below. There were kitchens, bedrooms, a dining room, and a number of open rooms.

This house was built during Paestumʻs Roman Period, 3rd century BC. The rich lived in private homes in the city or large villas in the country. Most people in the cities of Ancient Rome lived in apartments called insulae. The wealthy lived in single family homes called domus of various sizes depending on how rich they were. The impluvium in this house was made of marble and was well preserved because it was covered by a later inferior cover.

The impluvium is he sunken part of the atrium in a Greek or Roman house (domus). It was usually made of marble and placed about 30 cm below the floor of the atrium and emptied into a subfloor cistern. The impluvium was designed to carry away the rainwater coming through the compluvium of the roof. A substantial quantity of water caught in the basin of the impluvium filtered through the cracks, through layers of gravel and sand into a holding chamber below ground. A circular stone opening protected with a puteal allowed easy access by bucket and rope to this private, filtered and naturally cooled water supply.

When, around 600 BC, the Greeks took over the site, Poseidonia, they superimposed an orthogonal grid of streets and blocks onto the earlier aquatic landscape. This grid appears to have been completely developed as early as 500 BC. The main temples were erected in the city center.

In the Ist century BC when Paestum was a colonia latina, a town which retained some form of self-government, but was basically subject to Rome. The Curia was the building where the local town council met and the circular bench on which its members sat is evident in this picture. The magistrates administered justice and their archives were kept. The Curia was a brick building with plastered demi-columns, a typical element of Roman architecture.

Hera was the sister and wife of Zeus and the patron goddess of Poseidonia/Paestum. Terracotta votive figurines found in the sanctuary show female types normally identified as Hera. There is also an inscribed silver dish which declares ‘I am sacred to Hera: strengthen our bows’. This temple is one of the most well-preserved Doric buildings in Magna Graecia.

These votive offerings to the goddess Hera were made in Paestum. The offerings consisted of statuettes of draped female figures wearing cloaks with elegant hairstyles.

The Temple of Hera II was also used to worship Zeus and another deity, whose identity is unknown. This Attic black-figure container of perfumed oils (lekythos) with seated Zeus and Apollo and Hercules was found in the Temple del Prete, Tomb 24, first quarter of the 5th century BC.

(Rear left) Black-Glazed Bottle with lattice decoration containing scented ointments; (4) Small black-glazed jug and small black-glazed cup; (Rear middle) Vase for pouring and storing oil for oil lamps (askos); (6) Container with lid; (7) Terracotta models of fruit.

Identified on this picture are the parts of a Doric temple. The Doric order is the oldest and most widespread in continental Greece and Magna Graecia. Its main features are: absence of an actual base for the column; the simplicity of the capital, placed at the top of the column like a crown and consisting of a rounded moulding (echinus) and a square block (abacus); a smooth architrave with a frieze running along it in which slabs with three vertical groves (triglyphs) alternate with sculpted panels (metopes).

The Temple of Hera II has six columns along its shorter sides (as seen above) and fourteen columns along its longer sides. The columns do not have the typical 20 flutes on each column but have 24 flutes. The Temple of Hera II also has a wider column size and smaller intervals between columns. The entasis, or curve, of its columns give a stronger visual presence. This temple is aligned with a double peaked mountain considered to be sacred by the Greeks.

Seventy 6th-century metope reliefs were found in the area of an ancient Greek sanctuary complex dedicated to the goddess Hera in Magna Grecia (southern Italy). The buildings were constructed from the 6th to at least the 3rd centuries BC at the mouth of the River Sele located about 5 miles north of the Greek city of Poseidonia/Paestum.

This metope is from the Sanctuary of Hera at the mouth of the Sele River. A few kilometres from Paestum there was a temple complex at the mouth of the Sele river (Foce del Sele in Italian) dedicated to Hera. The temple is now all but destroyed, and little remains of several other buildings.

Found at the Sanctuary of Hera at the mouth of the Sele River. About 70 of the sixth-century BC Archaic metope relief panels on the temple and another building at the site were recovered. These fall into two groups, the earlier of which shows the story of the life of Heracles in 38 surviving reliefs; the later group, of about 510 BC, shows pairs of running women.

Found at the Sanctuary of Hera at the mouth of the Sele River.

Top of the doric columns consisting of a rounded moulding (echinus) and a square block (abacus). Because a Doric column is thicker and heavier than an Ionic or Corinthian column, it is sometimes associated with strength and masculinity. Believing that Doric columns could bear the most weight, ancient builders often used them for the lowest level of multi-story buildings, reserving the more slender Ionic and Corinthian columns for the upper levels.

Inside the Temple of Hera II there are two rows of seven columns, a mainland Greek feature that became more widespread in Sicily and South Italy at this time.

![Thomas Majorʻs 1768 drawing of the "Interior of the Temple of Neptune " [Hera II]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/567de29d841abaa3c9152fbd/1620173896401-0X4A7PYKTK75B5JVI62S/Thomas+Major%2C+Interior+of+the+Temple+of+Neptune+1768.jpg)

View of the cella in the Temple of Hera II. This double colonnade divided the cella into a nave and two side aisles. In ancient Greek and Roman temples the cella was a room at the center of the building, usually containing a cult image or statue representing the particular deity venerated in the temple.

US army company with its tranceiver office between the Doric columns in the Temple of Hera, September 22, 1943.

The earliest temple at Paestum is the so-called Basilica. When it was first rediscovered in the 18th century it was thought not to be a temple at all, as none of the entablature that formed the pediment at the end had survived. So it was named the Basilica, or town hall. However numerous little figurines of the goddess Hera, who was the wife of Zeus , the King of the Gods, have been found.

The temple was built in the middle of the 6th c. BC. Some unmistakeable features of the Archaic nature of the temple are the odd number of columns on the front line (nine while there are 18 along the sides) and the profile of the columns, with the obvious entasis (swelling) in the center, and the rather convex, “crushed” shape of the echinus (the rounded molding linking the top of the capitol to the shaft of the column).

Image of Hera seated on a throne (known as La Pestana - The Paestum Hera) holding a sacrificial cup and a pomegranate or a basket of fruit (left). Thousands of these figures were made in workshops at Paestum. Pomegranates symbolize renewal and rebirth.

The “flower woman” refers to terracotta votive offerings or alternatively as thymiateria (incense-burners) that were found in Paestum. The earliest and most diffused meaning interpretation of these peculiar figurines was related to the cult of Hera, attested at the Foce Sele Sanctuary.

The sanctuary Argive Hera, near the mouth of the Sele River, was strongly connected to navigation and water, as is often the case with sanctuaries of Hera. Many minature vases, mostly hydriskai, were offered to the goddess. They were probably used in rites where water was scooped and poured.

Hera holds a pomegranate in her rt. hand and a patera (bowl used for libation) in her left. The pomegranate fruit has been used throughout history and in virtually every religion as a symbol of humanity’s central beliefs and ideals, namely, life and death, rebirth and eternal life, fertility and marriage, and abundance. The pomegranate, as a symbol of fertility, was associated with Hera who was the goddess patron of childbirth.

The pomegranate is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub, widely considered to have originated in Persia, modern-day Iran, and to have been cultivated since ancient times. The pomegranate is attested in ancient Elam (southwestern Iran) during the 4th millennium (4,000 BCE), and then spread to the rest of the Near East, with the original shrub (Punica protopunica L.) reaching Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Syria, and Palestine by the end of the 3rd millennium. Sumerians (now southern Iraq) appear to have been involved in domestication of the pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), and the fruit quickly became an important symbol.

The brilliant red and yellow of the pomegranate’s skin, the blood-red juice, and its healthy properties create associations with human fertility, and thus life and death. In ancient Mesopotamian art pomegranates are often represented with the deities of fertility, fecundity, and abundance.

Pomegranate seeds were found in the principal cities of the 3rd millennium BC Syria-Palestine, such as Ebla and Jericho, and the spread of pomegranate in the Levant continued during 2nd millennium BCE.

By the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE, the pomegranate is found especially in funerary contexts in the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia), and it also achieves further symbolic value connected to kingship. Its image continued to be reproduced on textiles, wood, ivory, precious metals, as well as in symbolic ornaments.

During the 2nd millennium BCE, the pomegranate was an exotic fruit for urban aristocrats of the Near East and was exchanged as a luxury item, but it also had strong symbolic value both in the sacred and funeral spheres. The same symbolism was transmitted to Greek culture at the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE.

In ancient Greece, the pomegranate is also the fruit of the netherworld through the myth of Demeter and Persephone and Hades, which relates themes of fertility, death, and resurrection. (*N.B. Pomegranate color added for visibility)

In 7th and 6th century BCE the pomegranate appears as a standard element of Greek aristocratic tombs, both as a grave good or depicted on funerary vases. In Mycenean and later Greek mythology, Hera, wife of Zeus, receives a tree of golden pomes (μῆλη), probably pomegranates, which gave the gift of immortality. The pomegranate is one of the most common attributes of Hera in Western Mediterranean, especially in Southern Italy, where the goddess was widely worshipped.

It is probable that the diffusion of the pomegranate in the western Mediterranean is due to Phoenician expansion around the 10th century BCE, with Phoenician colonists carrying the fruit, and its symbolism to Sicily, the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, and then to the Etruscan and Roman worlds.

Based on the previous pictures and information, it is no wonder that Christianity also embraced the symbolism of the pomegranant, a fruit that has been used throughout history and in virtually every religion as a symbol of humanity’s central beliefs and ideals, namely, life and death, rebirth and eternal life, fertility and marriage, and abundance. In this painting, Botticelli shows Mary holding the pomegranate to symbolize Christ's Passion, the wealth of seeds conveying the fullness of Christ's suffering. Also, each figure wears a sad expression as if their mind is somewhere else thinking of Christ’s death. The seed of the pomegranate that the Madonna holds with the infant signifies that Christ will receive resurrection through rebirth just as the seed will cause the birth of a new plant.

![The Temple of Hera I (The Basilica) [550 BC]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/567de29d841abaa3c9152fbd/1617685723278-VCDET7ELVN48ETCCRJG0/SSL_5352_Hera+columns_sm.jpg)

This view of the side shows an excellent example of what is called entasis, that is making the columns cigar shaped, curving in at the top and leaning in slightly at the bottom. This is something very common in the earliest classical Greek temples as the Greeks believed that it was an important optical illusion as it made the columns appear vertical; later columns are straighter sided. Entasis therefore is generally considered to be a mark of early date.

Piranesi created 21 plates of his visit to Paestum, which were published posthumously in November 1778 in his book Différentes Vues de Pesto. Piranesi wrote, “‘Italian antiquities showed greater originality than those of Greece.” He argued that Romans had taken their architectural style not from the Greeks but from the Etruscans, early inhabitants of Italy.

Hera was the patron goddess of the city. Unlike the other temples, the dedication of this one is certain, thanks to inscriptions to Hera on the temple. An open-air altar was unearthed in front of the temple, where the faithful could attend rites and sacrifices without entering the cella (the holiest area accessed by priests).

In 1805, Felice Nicolas, Superintendent of Antiquities of the Kingdom of Naples and the two Sicilies, excavated the first necropolis near the north gate (Porta Aurea).

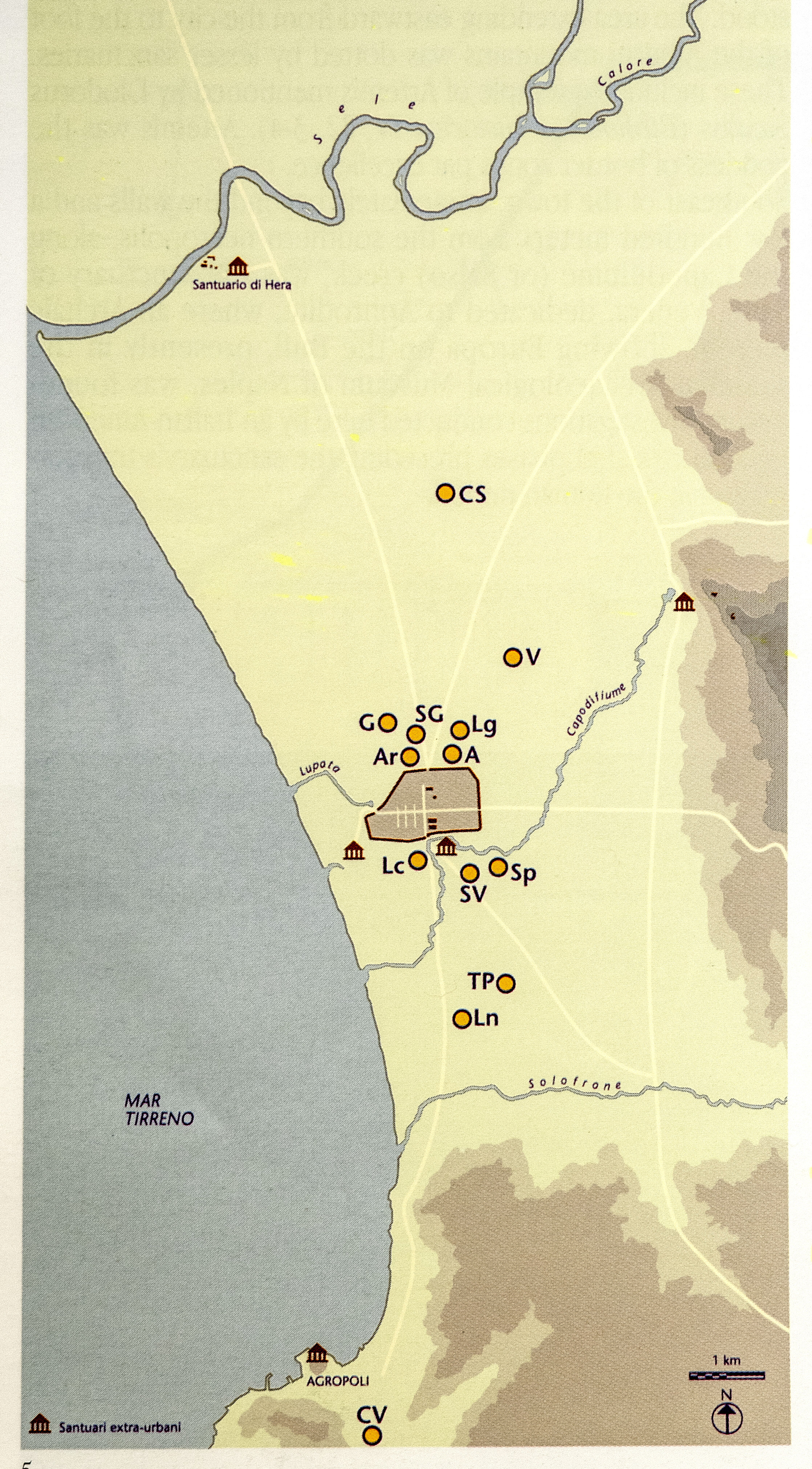

A necropolis (plural, necropoleis) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek νεκρόπολις nekropolis, literally meaning "city of the dead". The term usually implies a separate burial site at a distance from a city, as opposed to tombs within cities. This map shows the sites of the necropleis associated with Poseidonia/Paestum: A - Andriuolo; Lg - Laghetto; Ar - Arcioni; SV - Santa Venera; Sp - Spinazzo; Lc Licinella; SG - Spina Gaudo; G - Gaudo; V - Vannullo; CS - Capaccio Scalo; TP - Tempa Del Prete; Ln - Linora; CV - Contrada Vecchia.

This CIST tomb, i.e., a small stone-built coffin-like box used to hold the bodies of the dead has painted slabs, contains the skeleton of a man and the grave goods as they were found at the moment of discovery. The warrior has a triple-disc cuirass, two belts, a spear and a knife. Together with a black glazed cup. The slabs are decorated with bands and simple plant motifs, a pomegranate, a wreath and vine shoots with leaves.

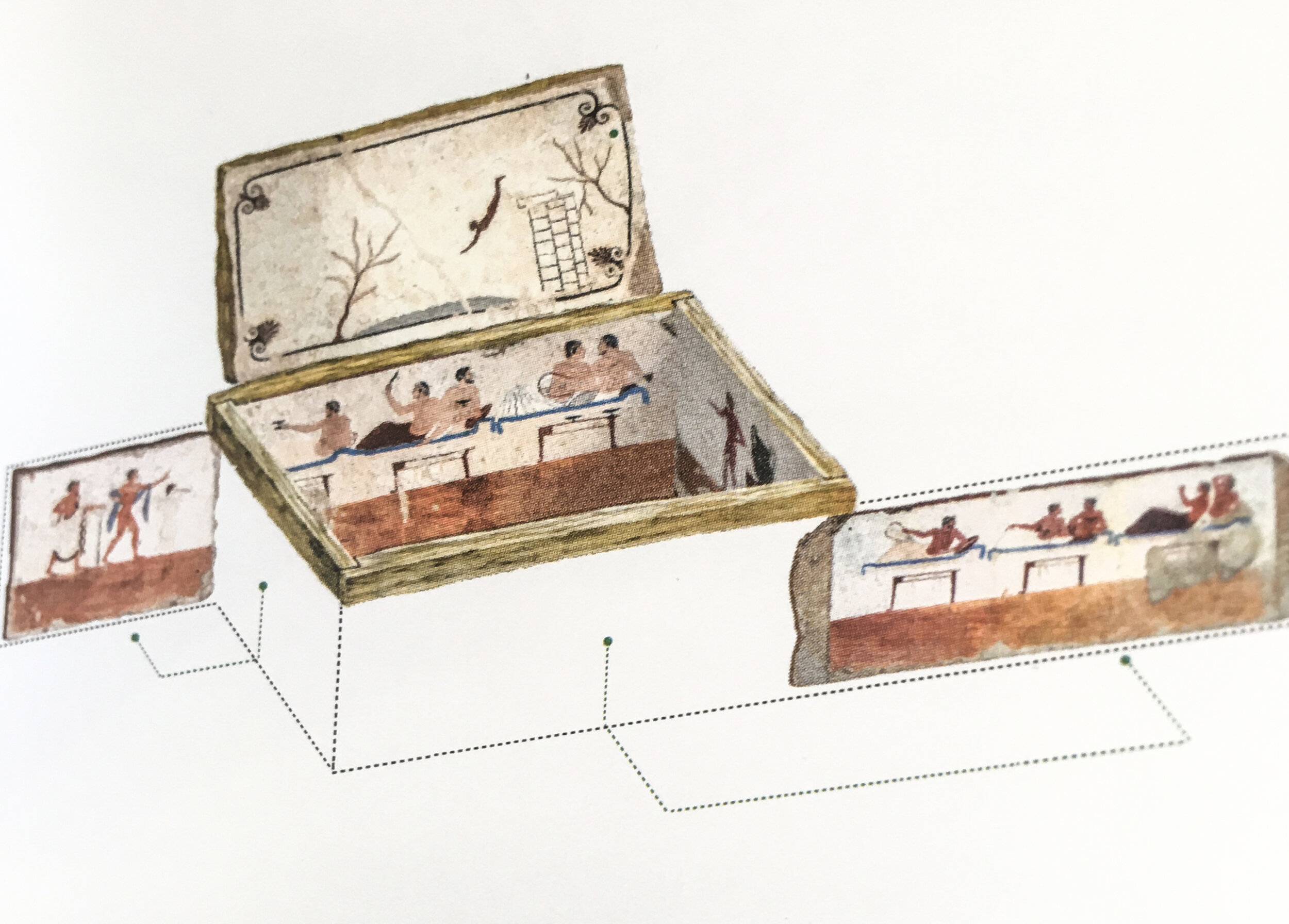

The Tomb of the diver is a cist tomb. The main slab is decorated with the famous scene of the diver while later slabs show a scene of symposium. This tomb is considered the only known archaic Greek tomb with figurative scenes in Paestum. The figures painted on the slabs of the tomb were painted on a layer of fresh plaster by two craftsmen. The figures show the presence of a preparatory drawing, made using a sharpened instrument, which formed the basis of the figurative composition.

All scholars agree that his scene is symbolic - an indication of a metaphorical transition from life to death.

The west wall of the tomb shows a cortege (a solemn procession, especially for a funeral) of guests. Here we see a small figure of a woman, dressed in white and playing the flute – the only woman shown in the tomb. At the centre is an athletic nude man, followed by an older man leaning on a stick.

At the other end, the east wall, is this painting of a youth holding a drinking cup in his hand which he has just filled from the large bowl behind,. This is a mixing bowl, in which the wine was mixed with water – the Greeks always drank their wine mixed with water – only barbarians drink their wine neat.

Dionysus is holding a drinking cup in his hand and with wine tendrils growing from his hair. To the left is a satyr, recognizable by his erect penis and animalʻs tail. He is holding a fine tripod suitable for holding a large wine jar, but usually purely decorative and given as a prize in the games or as an offering to the gods. During the Dionysian festival in Athens, a tripod was given to the winner so perhaps the satyr is carrying the tripod for Dionysus to present to the winner.

The participants at the symposium are portrayed in the final phase of the banquet when they abandon themselves to the pleasures of wine, eroticism, music, song and the game of kottabos, which consisted in skillfully flinging drops of wine at other cups.

The north wall slab is painted showing, left to right, a guest reaching out his wine cup, a guest playing kottabos with his wine cup, and, far right, a couple of lovers, one of whom holds a lyre.

Sometime around 400 BC, Paestum or rather Poseidonia, was conquered by the Lucanians. The Lucanians were one of the Samnite peoples who occupied much of central Italy and were the greatest rivals to Rome. Paestum remained Lucanian until 273 BC when it was conquered by Romans and became a Roman colony. The art work in this Lucanian tomb retains the traditional Paestan compositional device of simply juxtaposing the slabs. The long walls showed an identical subject, a Victory racing on her chariot.

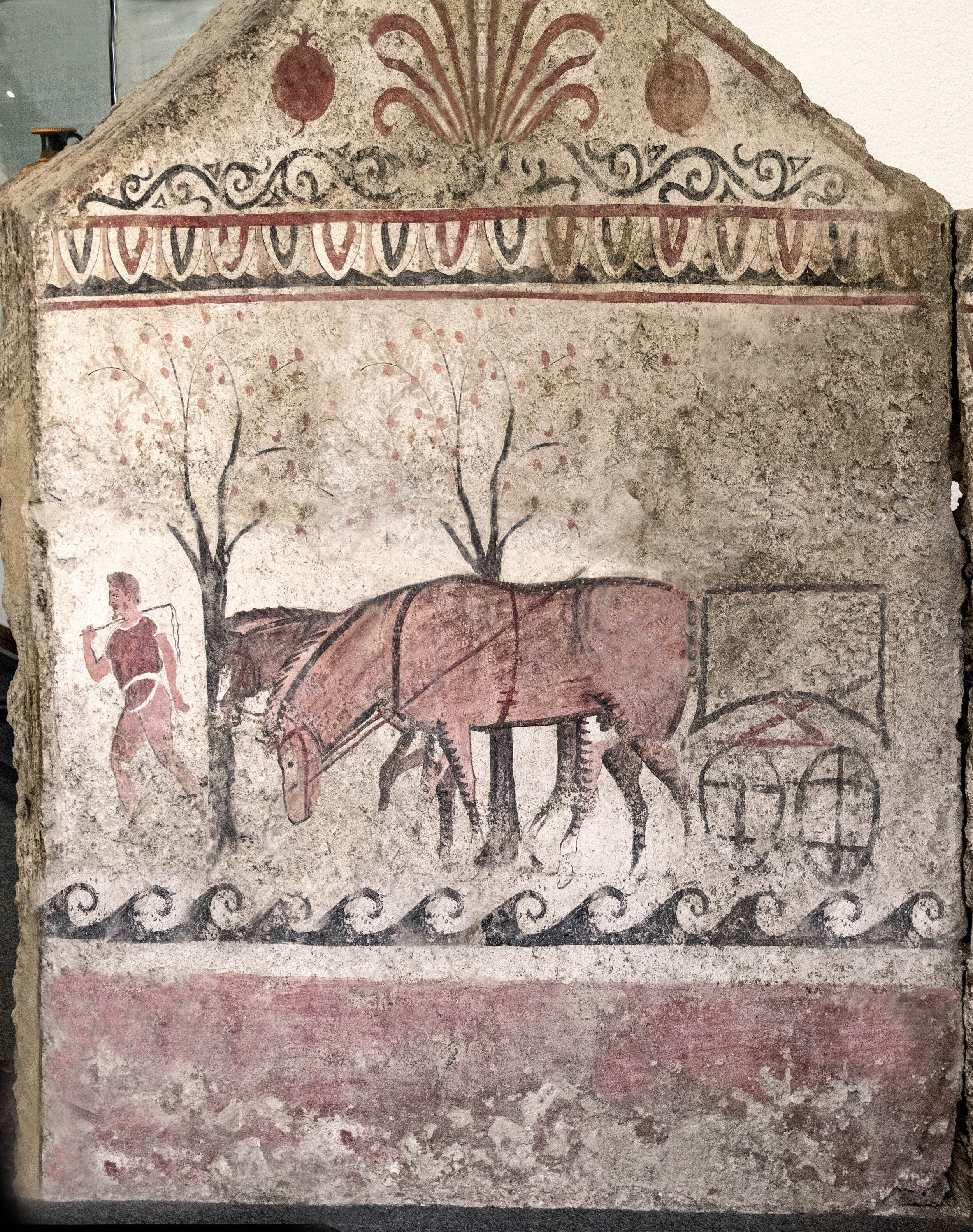

Paestumʻs Lucanian period is best known from the considerable number of tombs that are found in the surrounding area often with elaborate wall paintings. Painted on the eastern slab of this tomb is a cart being pulled by mules and led home by a farm laborer with a whip. The rural character of this painting is marked by a pomegranate tree, an indication that it may not be a typical rural idyll but rather a sad journey to the cemetery.

From 380 BC onwards, the most prestigious Lucanian tombs were painted with one of the most famous and commonly used scenes; The Return of the Warrior. The image, which appears exclusively in male burials, is that of a bearded horseman wearing armor (which is sometimes found in the tomb and was actually worn by the deceased), and carrying spears from which war booty hangs. The warrior, portrayed sitting astride a horse, is celebrated as he returns victorious to his community, and is welcomed by the woman who offers him the vessels for the libation.

“Winged Victory” was a very common allegory in contemporary official Greek art, and was widely adopted by Italic elites. A common motif in both male and female tombs is chariot racing whose driver sometimes wears a wind-blown cape on his back. In some cases the driver is replaced by Nike, an allegorical figure representing victory, both in life and death. Nike assumed the role of the divine charioteer. Nike flew around battlefields rewarding the victors with glory and fame, symbolized by a wreath of laurel leaves (bay leaves).

Here we see the metamorphosis of the dead rider to an heroic figure. A large figure of a rider faces a crater containing a sort of bouquet. This rider. who wears Greek-style dress, but with some ornamental details typical of Italic equestrian statues, is one of the rare known painted parallels for the honorary equestrian statues being erected in Rome at the same time.

The form of the plate was called a "pinax" or "pinakion", meaning "tablet," because of its flat shape. The fish plate's form was that of a dimpled disk elevated on a pedestal, in other words, round and flat with a small cup in the center of plate designed to hold oil or sauce. The South Italian fish plates are characterized by decoration in which the fish's bellies are oriented towards the sauce cup at the center of the plate.

An Ideal image of women and their virtues as wives, mothers, and protectors of their family and domestic property is celebrated through funerary honors, a custom typical of the Italic and, later, the Roman world. According to the historians Livy and Plutarch, after the seizing of Rome by the Gauls in 390 BC, Camillus rewarded the matrons who had donated jewelry to support Romeʻs war effort with the right of elogium (eulogy), until then reserved to men.

Behind the “weeping mournersʻ on the wall are the hanging pomegranates.

Only aristocratic women were entitled to painted tombs, which initially lacked figured scenes, or else were decorated with images of funerary games, e.g., shown here as a biga (two-horse chariot) race with the column in the middle of the wall representing the meta around which the chariots turn.

Around the middle of the 4th c. BC, an exclusively female figurative program was created. This scene shows the deceased woman as a sitting matron spinning wool with the assistance of a handmaid standing in front of her. The latter has short hair and bare arms, and wears a long tunic of a uniform color.

in Lucaniun Paestum aristocratic women had a prominent role in society. It was their task to watch over their familyʻs possessions and guarantee the continuity of their husbandʻs lineage. Female grave-goods included typical funerary vases, jewelry, and in the cases of especially important women, a hydria, i.e., vase used as a water container, and a lebes (above), the nuptial object par excellence.

A reflection of the critical role of women in society is found in this version of the Return of the Warrior motif where, as the woman reaches the libation vases out to her husband, she becomes the instrument of a rite of passage through which the warrior is cleansed of the blood shed in battle and can regain his place in this family and in the political community.

As you may have observed already, the pomegranate appears in many of the tomb paintings on display in the Paestum museum. The pomegranate when ripened in the later part of the year represents the late years of a woman. The red juicy seeds are related to blood and it is called the food for dead in some places in Greece.

On the vases accompanying deceased men or women in their tombs, water is a recurrent element. On this lekane vase, a woman looks at herself in the mirror while a naked man reaches out a twig to her. Lekane were a late form of painted vase of southern Italy with upright handles and often with a cover of elaborate form.

A pelike is a one-piece ceramic container similar to an amphora. It has two open handles that are vertical on their lateral aspects and even at the side with the edge of the belly, a narrow neck, a flanged mouth, and a sagging, almost spherical belly. Pelikes are often intricately painted, usually depicting a scene involving people, e.g., as seen here with women at a fountain. They were most likely used for carrying wine. The shape first appeared at the end of the 6th century BCE and continued to the 4th century BCE.

The fresco depicts a servant woman carrying a hydria (a water-carrying vase) on her head with hanging pomegranates. In this case, the water is for the burial ritual, but we can imagine that women and young girls carried home the water they drew from wells and fountains every day in the same manner, balancing vases on their heads.

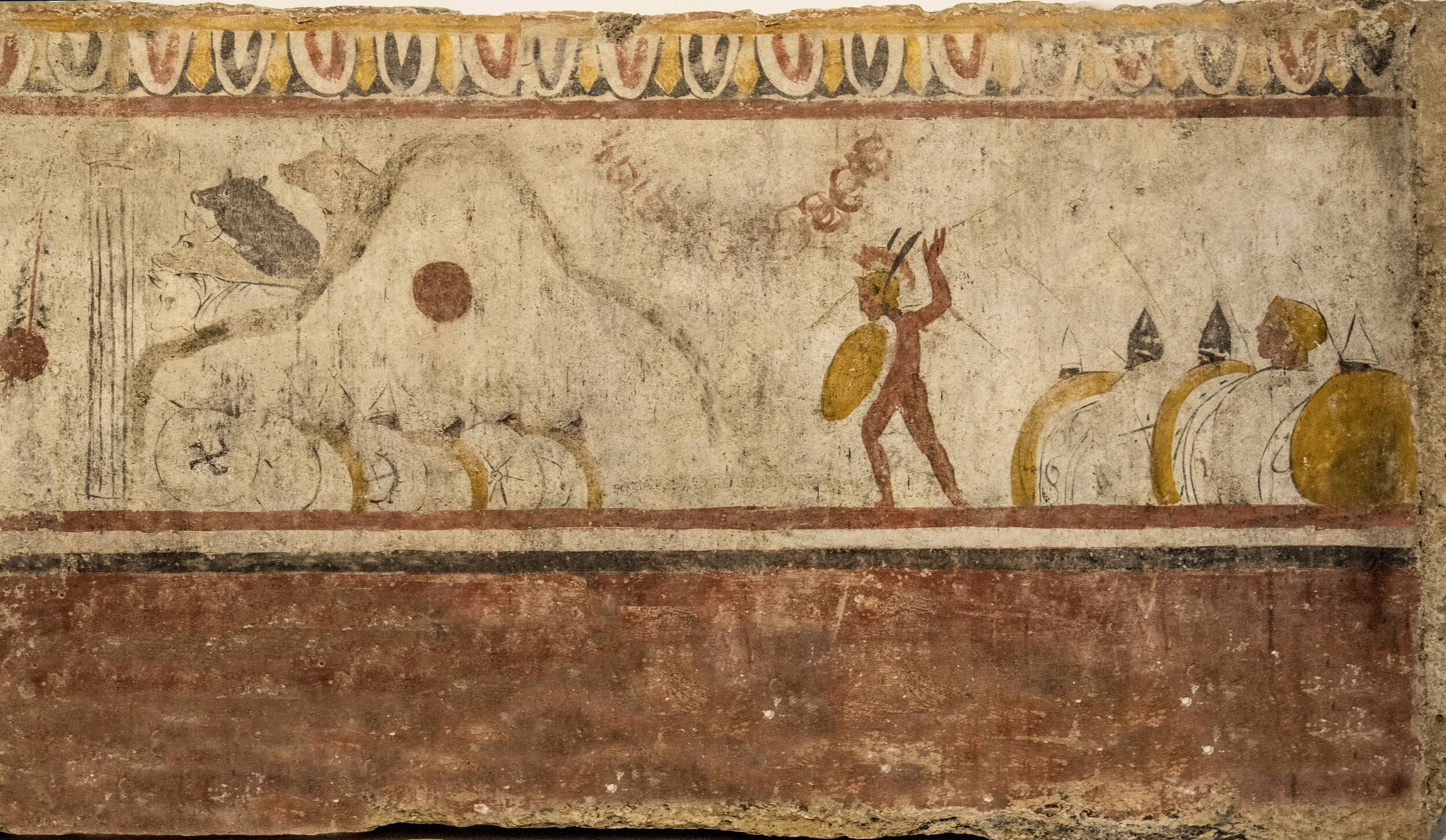

In the second half of the 4th century BC, there was an increased tendency toward narration. Above, two armies engage in combat in landscape picturesquely evoked by a mountain beyond which are silhouetted disproportionately large oxen. The deceased is celebrated as the victorious protagonist of the battle. His side is led by a naked character who, with a shield on his arm and a helmet graced by two black plumes on his head, brandishes his spear against the enemy soldiers. The scene can be viewed as an epiphany of the Italic Mars, whose presences alludes to the victory of the deceasedʻs side.

During the 4th c. BC increasing stress was laid on age distinctions between male roles within the family and in society. Males fall into three categories: youths, warriors in their prime, and old men. In the paintings, age class is denoted by physical characteristics (presence of absence of a beard, hair color), dress (long cloak trimmed in red, richly decorated, or graced by a simple red stripe; short tunic; shoed vs. bare feet), weapons (notably the lance), and vehicles (notably a carriage drawn by mules). Old men, the patres familias, exercised the political function.

The fish images could represent symbolic offerings for the dead. On the other hand, these plates could just as well be objects which were in popular use among the living, placed in tombs for the deceased to continue using in the hereafter.

This collection of chicken-related artefacts shows that the chicken had a role that extended beyond the next meal, linking them with deities, such as Mercury, and ideals, such as virility and abundance, which people may have tried to connect with by owning such items. Chickens were associated with wealth and prosperity and likely acted as a symbol of luck and good fortune.

At the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd century BC, the number of painted tombs decreases considerably. Some are now decorated exclusively with ornamental motifs.

Known officially as the Chiesa dell'Annunziata the historic landmark is located behind the museum. It is also referred to as the Paleo-Christian Basilica. When the city was Christianized in the 4th century, they used the abandoned Greek temple as their meeting place. Then in the 5th century stones and columns from the ancient city were used in the building, which was originally open to the elements like the ancient temples nearby. Around the end of the 5th century, the church became a "closed basilica" with the addition of outer walls and a vault.

By the 9th century the inhabitants had all fled due to Saracen invasion and malarial conditions, moving inland and uphill to Capaccio. The ancient area was left desolate and forgotten for centuries. here was an attempt by the bishop to restore the basilica in the 1600s, giving it an unfortunate Baroque make-over. However, it remained largely unused and the entire area was little visited even by local residents.

The basilica was restored and some of the Baroque decorations stripped to reveal the original architecture and the ancient pieces used in its construction. You can see the original Greek columns and the old floor pavings in this simple interior, that is traditionally called "the Byzantine church"

The basilica was restored and some of the Baroque decorations stripped to reveal the original architecture and the ancient pieces used in its construction. You can see the original Greek columns and the old floor pavings in this simple interior, that is traditionally called "the Byzantine church."

Driving from Paestum toward Calabria, luckily we came upon the Pizzeria Positano “percheʻ abbiiamo molti fame!”

This was a great pizza - with mounds of fresh mozzarella buffalo and prosciutto ham. Buffalo mozzarella is a mozzarella made from the milk of Italian Mediterranean buffalo. It is a dairy product traditionally manufactured in Campania, especially in the provinces of Caserta and Salerno. Prosciutto is made from either a pig's or a wild boar's hind leg or thigh, and the base term prosciutto specifically refers to this product.

I loved the picture of the Italian peninsula on the bottle.