The Stanza di Eliodoro was set up by Julius II (r. 1503-13) for the private audiences the Pope would grant to important political, religious and diplomatic dignitaries. The frescoes were designed to reflect the importance of the room's purpose and the meetings that took place there. The general theme of the pictorial decoration is the protection bestowed by God on the Church. Raphael painted four biblical episodes on the walls: The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the temple, the Mass of Bolsena, the Liberation of St. Peter and the Meeting of Leo the Great with Attila.

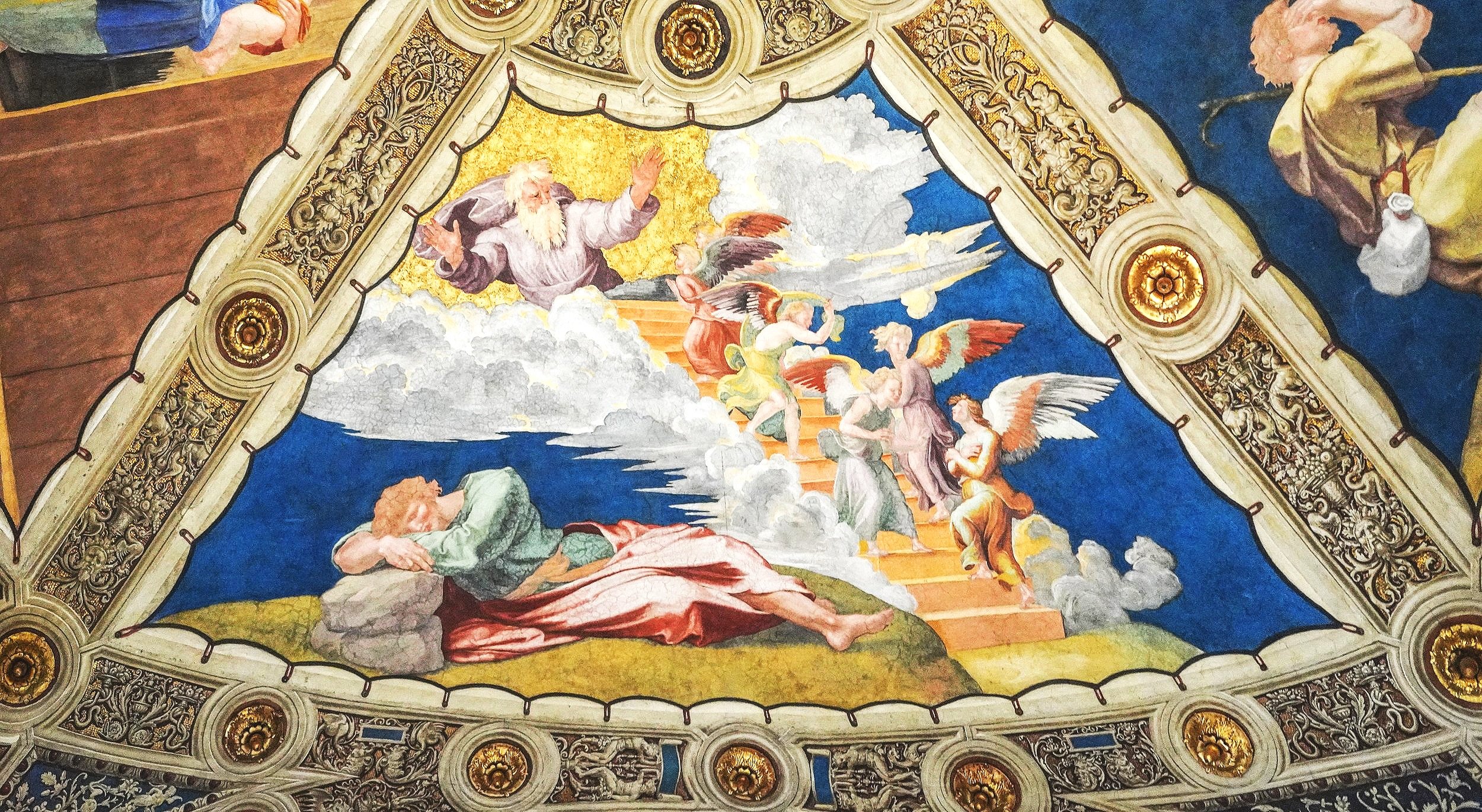

Raphael painted the four frescoes of the vault representing episodes of divine intervention in the history of Israel: Moses before theBurning Bush (Exodus 3: 1-12), the Announcement of the Flood to Noah (Genesis 8: 15:20), Jacob's Dream (Genesis 28: 10-22)., and the Sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis 22:1-14). Raphael continued the theme of divine intervention and protection in the wall frescoes below each ceiling vault.

The story of Moses Before the Burning Bush promotes the theme of divine intervention and protection that pervades all of the Raphael frescoes in this room. Exodus 3:7 states: The Lord said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptian…."

Heliodorus (far right, lying down) was sent to steal the treasure from the Jewish temple, money that had been reserved for widows and orphans. Pope Julius II, commissioner of the work, and celebrator of the painting's sub-themes of papal authority and protector of the faithful, witnesses the scene, sitting on his litter carried by his chair bearers, and surrounded by the widows and children who were to be the beneficiaries of the stolen money. The fresco includes a self-portrait of Raphael as one of the bearers of the sedan, to the left, directly below the Pope’s left hand.

This detail from The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple illustrates the biblical episode from 2 Maccabees (3:21-28), in which the high-priest OniasIII prays for God to prevent the theft of synagogue’s treasure. The menorah in front of the priest shows that this event occurs in a synagogue. Thus, the fresco supports a sub-theme for the Room, important for Counter-Reformation efforts, i.e., the sacredness of the services, including sacraments, occurring inside church buildings.

Heliodorus (on the right, lying down) was ordered by Seleucus IV Philopator the king of Syria and the Seleucid empire (187–175 BCE), to seize the treasure preserved in the Temple in Jerusalem. Seleucus IV mostly spent his reign in attempts to pay the large indemnity his father Antiochus had left him as a result of the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC), the main clause of which saw the Seleucids agree to pay a large indemnity to the Roman Republic. As Heliodorus was in the act of stealing the treasure, answering the prayers of the high priest Onias III, God sent a horseman assisted by two youths with whips to expel Heliodorus. One message of the event is God will protect the Church from looting of foreign invaders, as in Raphael's fresco “The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila,” located in the same room.

According to Genesis 22:1-14, God commands Abraham to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice. When Abraham “reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son… the angel of the Lord called out to him from heaven, and said, “Do not lay a hand on the boy. Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.” Abraham looked up and saw a ram and sacrificed it instead of Isaac. The story promotes themes implied in the Room’s frescoes, i.e., protection of the faithful through both divine intervention and papal authority.

The Mass at Bolsena depicts a Eucharistic miracle that is said to have taken place in 1263 at the church of Santa Cristina in Bolsena. A Bohemian priest who doubted the doctrine of transubstantiation was celebrating mass, when the bread of the eucharist began to bleed. The blood that spouted from the host fell onto the tablecloth in the shape of a cross and he was reconverted. The Mass of Bolsena and the fresco above it, The Sacrifice of Isaac, manifest the same theme, i.e., Abraham was willing to spill the blood of his son in sacrifice, as later did God the Father; both acts illustrate that God’s grace saves and protects those who believe.

In a group on the far-left side of the Mass of Bolsena altar, Raphael included Felice della Rovere (c. 1483 –1536), wearing a black robe, holding a red hat, and looking up at the host. Felice was the illegitimate daughter of Pope Julius II. Born in Rome to Lucrezia Normanni and Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (later Pope Julius II), she became one of the most powerful women of the Italian Renaissance, wielding extraordinary wealth and influence both within and beyond the Roman Curia. In particular, she negotiated peace between Julius II and the Queen of France.

Present in this painting is a self-portrait of the artist, Raphael, as one of the Swiss Guard in the lower right of the fresco, facing out with bound-up hair. This is another instance in which Raphael has placed himself in his paintings. Also shown in the work is Pope Julius II (1443–1513), kneeling to the right of the altar. The four cardinals to his right have been identified as Leonardo Grosso della Rovere, Raffaello Riario, Tommaso Riario and Agostino Spinola, relatives of Julius.

In The Mass of Bolsena Raphael depicts the Bohemian priest celebrating mass at the Church of Santa Cristina in 1263 when the blood of Christ purportedly spouted from the Holy Eucharist. The following year, in 1264, Pope Urban IV instituted the Feast of Corbus Christi to celebrate this miraculous event.

According to the story of The Mass of Bolsena, when the blood of Christ spouted from the host and fell onto the tablecloth in the shape of a cross, the priest who had doubted transubstantiation was reconverted. The blood-stained Corporal of Bolsena is still venerated as a major relic in the Orvieto Cathedral. The fresco reinforces the theme of the importance in one's personal belief in God and the authority of the Catholic Church.

The Cathedral of Orvieto was constructed under the orders of Pope Urban IV to commemorate and provide a home for the Corporal of Bolsena, the subject of Raphael’s Mass at Bolsena. To escape conflict in Rome, a papal palace was attached to the Cathedral that served as a refuge for five popes in the 13th c.: Urban IV (1261–1264), Gregory X (1271–1276), Martin IV (1281–1285), Nicholas IV (1288–1292) and Boniface VIII (1294–1303).

A mosaic of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary is in the middle of the second level of the façade, under the rosette window. The large rose window was built by the sculptor and architect Orcagna between 1354 and 1380. In the niches above the rose window stand the twelve apostles. The center of the rose window holds a carved head of the Christ. Discovering the other many elements of this façade is worth the research.

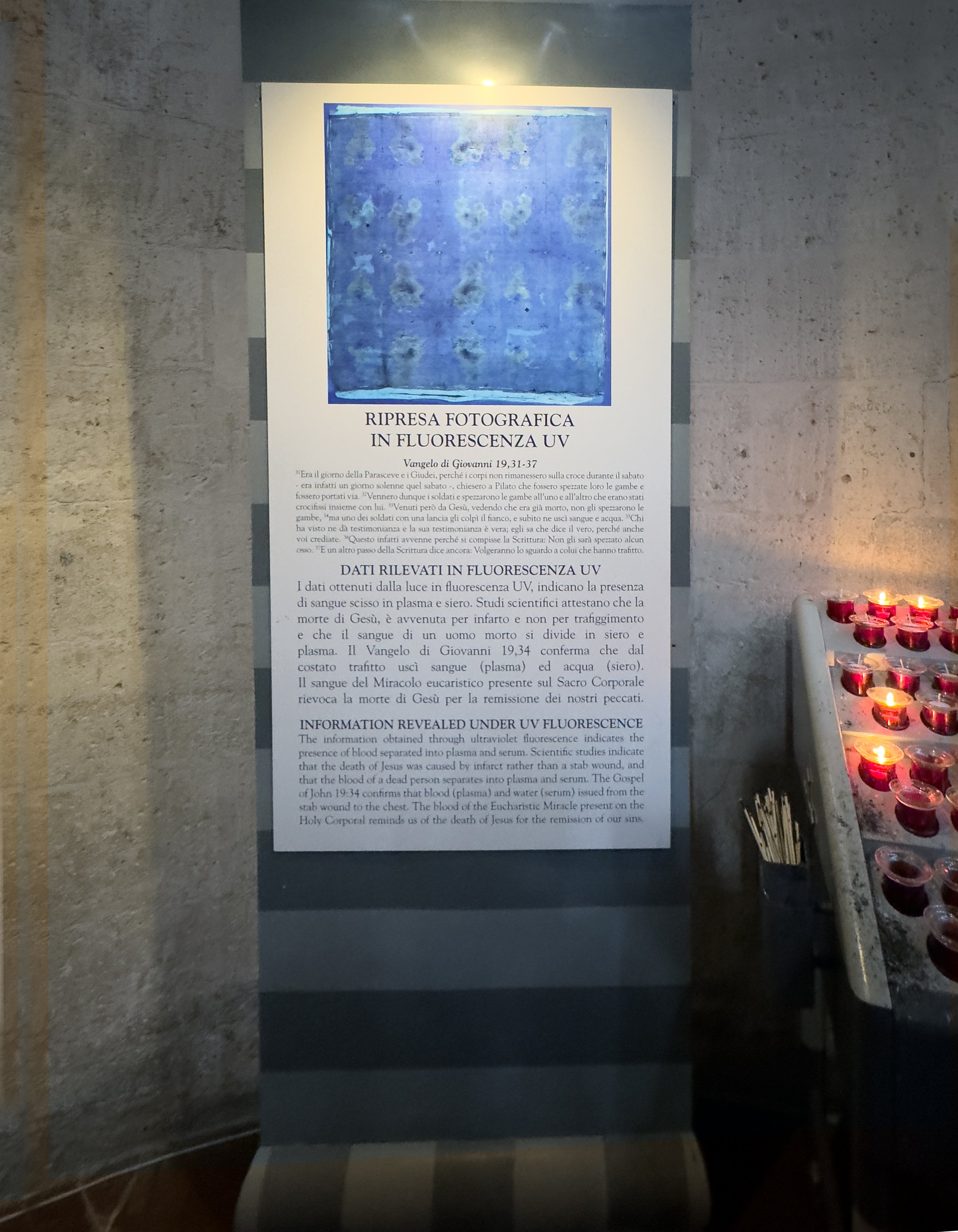

Outside the chapel the following statement is presented: The information obtained through ultraviolet fluorescence indicates the presence of blood separated into plasma and serum. Scientific studies indicate that the death of Jesus was caused by infarct rather than a stab wound, and that the blood of a dead person separates into plasma and serum. The Gospel of John 19:34 confirms that blood (plasma) and water (serum) issued from the stab wound to the chest. The blood of the Eucharistic Miracle present on the Holy Corporal reminds us of the death of Jesus for the remission of our sins.

The actual linen, purportedly stained by Christ’s blood, and the topic of Raphael’s Mass of Bolsena, is stored in the Reliquary of the Santo Corporale in the Chapel of the Corporal, built between 1350-1356. The miracle of the bleeding host involved a priest who became skeptical of the transubstantiation dogma.

Behind the tabernacle containing Holy Corporal linen is a fresco of the Crucifixion of Christ at Golgotha, showing Christ and two convicted thieves hanging on crosses. The Gospel of John states that, after Jesus's death, one soldier pierced his side with a spear to be certain that he had died, and blood and water came out (John 19:34). In front of the tabernacle and reliquary, two marble angels point to the other wall frescoes, i.e., one points to the left wall depicting the history of the Eucharist and one points to the right wall depicting the miracles concerning the bleeding host throughout church history.

The left middle-row panel of this wall fresco records the 1263 Miracle of Bolsena, showing the blood of Christ on the linen at the mass; the right middle-row panel shows the presentation of the Corporal of Bolsena with Christ’s blood to Pope Urban IV. The left bottom-row panel depicts the Corporal of Bolsena linen being presented to the people of Orvieto.

This 14th century fresco teaches the dogma of transubstantiation, i.e., the consecrated host and wine are actually the body and blood of Christ, by presenting priests in mass during the consecration of the host as raising the actual body of Christ, shown in the panels in the top and bottom center. Also, Christ, the Eucharist, stands next to the chalice as the priest consecrates the wine, changing it into Christ's blood (bottom right panel).

On the wall below the ceiling fresco of Jacob's Dream, is the Liberation of Peter, painted above and on each side of a window. The story is taken from the Acts of the Apostles, Herod the king, as the narrative says, "stretched forth his hands to vex certain of the church. And he killed James the brother of John with the sword. And because he saw it pleased the Jews, he proceeded further to take Peter also."

The story of Jacob's Ladder refers to the vivid, prophetic dream in which Jacob sees a ladder stretching from heaven to earth. The story of Jacob's ladder is often interpreted as a message of divine guidance, promise, and protection. It signifies God's covenant with Jacob and his descendants, who would go on to become the twelve tribes of Israel. It is also considered a significant moment in the life of Jacob, setting the stage for his transformation and spiritual growth, and affirming Jacob as the father of God's chosen people, the Israelites.

Liberation of St Peter from Prison as described in the Acts of the Apostles alludes to the divine protection granted to the pontificate. The fresco shows three scenes in symmetrical balance formed by the feigned architecture and stairs. In the center the angel wakes Peter, and on the right guides him past the sleeping guards. On the left side one guard has apparently noticed the light generated by the angel and wakes a comrade, pointing up to the miraculously illumined cell.

In the center of The Liberation of. St Peter the angel appears in the compartment over the window in a blaze of light, and this light illuminates all the other figures. It is as if Raphael meant to make it clear that the supernatural light from the angel was brighter and more intense than the light which falls from natural means. Thus, The Liberation of Peter, like the Expulsion of Heliodorus, keeps in mind the power of the divine over the human.

The Pact between God and Noah and The Meeting of Leo I and Attila complement each other by expressing the theme of divine intervention and protection. The Meeting of Leo I and Attila, on the west wall, was the last fresco painted in this room. Initially, Raphael depicted Leo I the Great, with the face of Pope Julius II but after Julius’ death in 1513, Raphael changed the painting to resemble the new pope, Leo X.

Genesis 9 states, “Then God said to Noah and to his sons with him: I now establish my covenant with you and with your descendants after you and with every living creature that was with you—the birds, the livestock and all the wild animals, all those that came out of the ark with you—every living creature on earth. I establish my covenant with you: Never again will all life be cut off by the waters of a flood; never again will there be a flood to destroy the earth." The covenant is an Old Testament iteration of the Heliodorus Room theme of divine intervention and protection; it also could be interpreted as a compact between God and mankind to care for and protect all living things on earth.

The Pope and the Hun conqueror met in 452 in northern Italy. According to the legend, the apparition of St. Peter and St. Paul in the sky, armed with swords, persuaded Attila not to invade Rome. Raphael emphasizes this divine intervention by having a startled Attila with his recoiling arms and helmetless head looking up at Sts. Peter and Paul in awe. In contrast, Attila’s black horse, in the middle of the fresco, calmly exchanges eye contact with us while the Pope, on the left, simply raises his had to repel the invaders.

As pontiff, Leo X became known for his patronage of the arts in Renaissance Rome and the luxurious lifestyle associated with it. He infamously said, “God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.” Under his tenure, Leo continued the project of rebuilding St. Peter’s Basilica, begun under Julius II, and commissioned famed Renaissance artists Michelangelo and Raphael for the task. Raphael was also charged with decorating the pontifical palaces and painting the tapestries in the Sistine Chapel.